Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

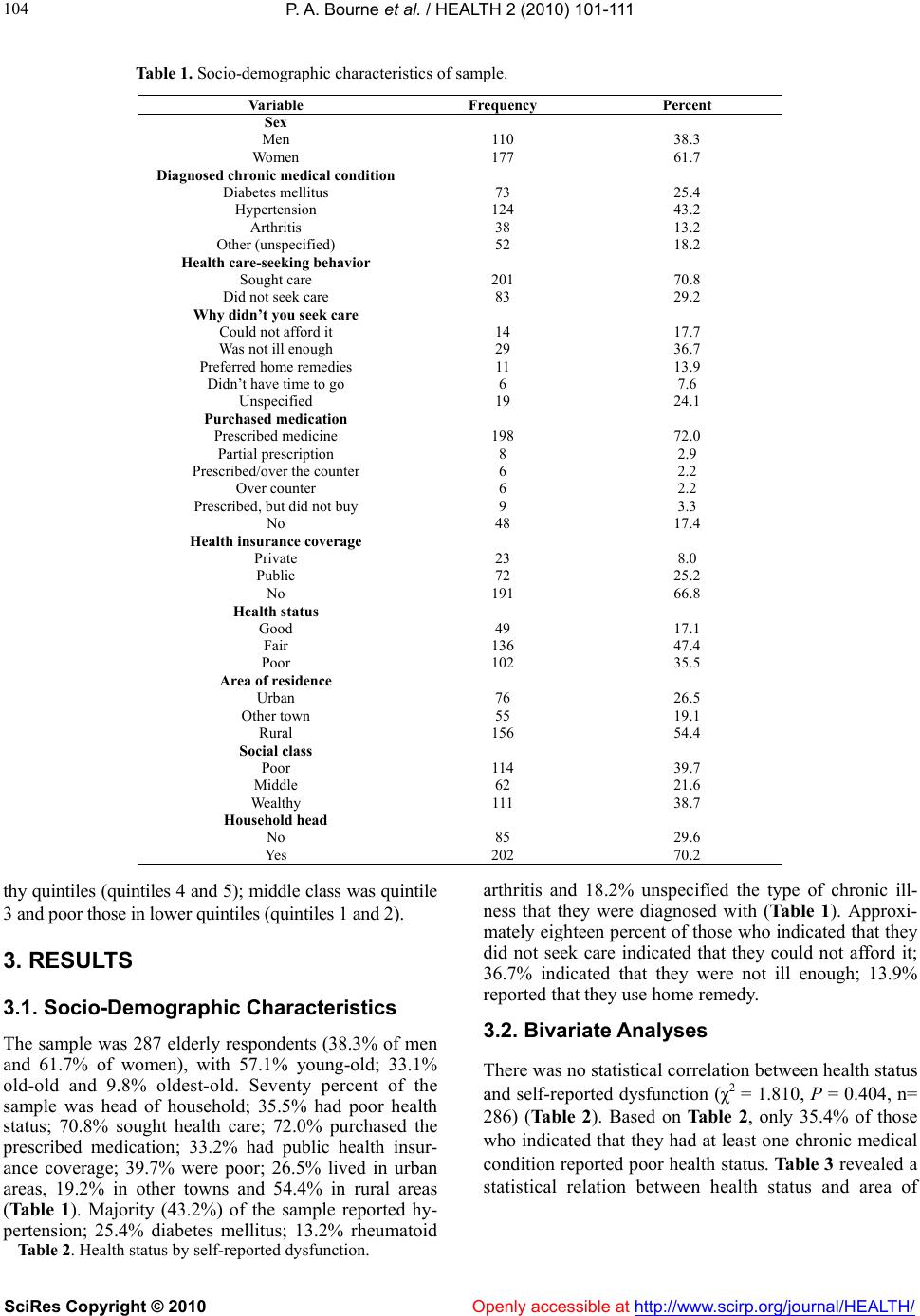

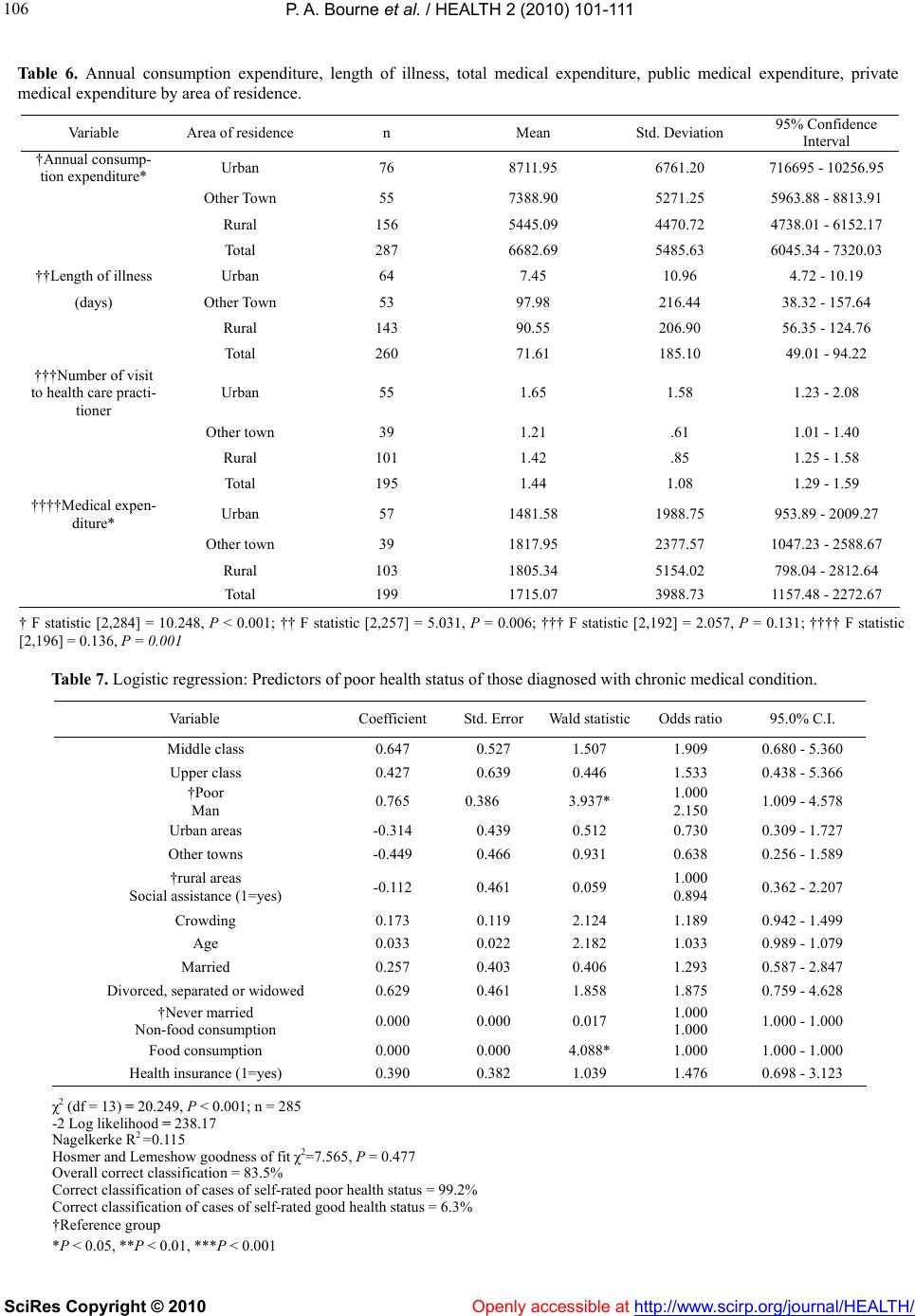

Vol.2, No.2, 101-111 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.22017 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Socio-demographic determinants of health status of elderly with self-reported diagnosed chronic medical conditions in Jamaica Paul. A. Bourne1*, Donovan. A. McGrowder2 1Departments of Community Health and Psychiatry, The University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica; paulbourne1@yahoo.com 2Pathology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, the University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica Received 29 October 2009; revised 9 December 2009; accepted 14 December 2009. ABSTRACT Objectives: The aim of the current study is to examine the health status of elderly in rural, peri-urban and urban areas of residence in Ja- maica, and to propose a model to predict the social determinants of poor health status of elderly Jamaicans with at least one chronic disease. Methods: A sub-sample of 287 re- spondents 60 years and older was extracted from a larger nationally cross-sectional survey of 6783 respondents. The stratified multistage probability sampling technique was used to draw the survey respondents. A self-adminis- tered questionnaire was used to collect the data from the sample. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the demographic characteris- tics of the sample; chi-square was used to in- vestigate non-metric variables, and logistic re- gression was the multivariate technique chosen to determine predictors of poor health status. Results: Almost thirty six percent of the sam- ples had poor health status. Majority (43.2%) of the sample reported hypertension, 25.4% dia- betes mellitus and 13.2% rheumatoid arthritis. Only 35.4% of those who indicated that they had at least one chronic illness reported poor health status and there was a statistical relation be- tween health status and area of residence [χ2 (df = 4) = 11.569, P = 0.021, n = 287]. Rural residents reported the highest poor health status (44.2%) compared to other town (27.3%) and urban area residents (23.7%). Conclusions: Majority of the respondents in the sample had good health, and those with poor health status were more likely to report having hypertension followed by dia- betes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis. Poor health status was more prevalent among those of lower economic status in rural areas who re- ported greater medical health care expenditure. The prevalence of chronic diseases and levels of disability in older people can be reduced with appropriate health promotion and strategies to prevent non-communicable diseases. Keywords: Older; Chronic Illness; Social Determi- nants; Jamaica 1. INTRODUCTION The Caribbean has been identified as the most rapidly ageing region of the world. Between 1960 and 1995, there was a 76.8% increase in the elderly population [1]. Among its regional island states, the average growth rate in the elderly population was approximately 5.3% for the 1995-2000 periods. The elderly as a percentage of total population was 4.3% in 1950 and is estimated to reach about 15% by 2020 [1]. In Jamaica, a similar pattern has been observed with a clear and rapidly rising trend in the elderly as a proportion of the population [2]. By 2025 as much as 1 in 7 persons will be elderly. Moreover, char- acterizing this pattern of increasing elderly is the differ- ential growth rates within the various sub-age groups over age 60, with the 75 years and above age group ex- pected to double moving from 2.8% currently to 4.0 % in 2025 [3]. Eldemire [4] noted that the elderly in Ja- maica represents 10% of the population, and that they were for the most part mentally competent and physi- cally independent. With a calculated life expectancy of 75.5 years [5], the burden on the healthcare system can be expected to increase. The epidemiologic transition in the Caribbean over the last 40 years has produced an epidemic of life- style-related chronic non-communicable diseases [6]. Among these are obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hyper- tension, along with such complications as stroke, heart disease, and amputations [6]. Cardiovascular disease is by far the leading cause of death at older ages in devel- oping countries, although the impact of communicable  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 102 diseases remains considerable [7]. One comprehensive analysis attributes nearly 46 percent of all deaths among women aged 60 and over in developing countries in the early 1990s to cardiovascular disease; the corresponding figure for older men was 42 percent [7]. Older people with diabetes mellitus are at particularly high risk for heart disease, stroke, eye damage, kidney disease, limb amputation and depression. In the Survey on Health and Well-Being of Elders (SABE), among those reporting diabetes, at least 60% reported visual problems with or without eye glasses. Among those reporting at least two chronic diseases, 25% had symptoms of depression [8]. Furthermore, SABE indicates that an average of 70% of women aged 60 years and older have at least one poten- tially disabling condition, such as low vision, rheuma- toid arthritis, or urinary incontinence [8]. In developed countries, the health and social status of the elderly has received a fair amount of attention [9]. Within the Caribbean, some progress has been made in terms of research on the elderly. Braithwaite [10] noted that data on the Caribbean elderly were extremely lim- ited. With the continuing aging of the population in the Caribbean, gerontological research has devoted increas- ing attention to those at very advanced ages [11] and in recent years, there has been increasing interest in issues relating to health of the elderly in the Caribbean. Pat- terns of mortality at the most advanced ages are of inter- est in their own right, indicating variation in health status and well-being among this group. Moreover, differences in mortality and trends in them may give clues about the likelihood of a further extension of life expectancy [12]. Rural populations in Caribbean countries generally experience excessive deficiencies in health care access, social services, and other goods and services needed for healthy living. Rural residence has significantly influ- enced health care access and health status. Urban resi- dents consistently reported better health status than rural residents and greater satisfaction with their health care [13]. Rural residents are more often uninsured [14], have greater distance to travel for their health care needs [13], and are more often plagued by resource inaccessibility [15]. Using poverty to proxy resource inadequacies wh- ich increased inaccessibility, in 2007; rural poverty was 2.5 times more than urban poverty (i.e. 6.2%) and 3.8 times more than urban poverty (i.e. 4.0%) [16,17]. Rural residents in Jamaica are poor and a greater proportion of them reported having chronic illnesses, with an even smaller population having insurance of any kind (7.6% in rural areas versus 25.0% in urban areas) [16]. While national averages provide insights into the ine- qualities in the nation, the current study on a sub-popu- lation provides health policy practitioners with a com- prehensive understanding of the issues experienced by elderly Jamaicans particularly public health problems that presently exist in this population. Among these is the fact that rural and peri-urban residents spent 11 and 14 times more days experiencing illnesses than urban resi- dents. Another public health problem is the percentage of elderly population with chronic illness compared to the general population. Statistics revealed that 12% of Ja- maicans had diabetes mellitus; 22.4% had hypertension and 8.8% had rheumatoid arthritis [17]. However, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the elderly was 2.1 times more than the general population. Similarly, the prevalence of hypertension and rheumatoid arthritis in elderly Jamaicans were 1.9 and 2.1 times respectively more than in the general population. The public health problem also includes reasons why some elderly are un- able to seek care despite health care being free for this group (since 2006). Of those who did not seek medical care, 18% indicated that they could not afford it and 38% reported that they were not ill enough (i.e. after self-as- sessment of health and image of health care). Hence, the aims of the study were to 1) examine the health status of elderly Jamaicans in rural, peri-urban and urban areas of residence; 2) establish a model to predict the social de- terminants of poor health status of elderly Jamaicans who have reported at least one chronic disease, and 3) provide information that could assist health care professionals to specifically and adequately address the health needs of the elderly in Jamaica. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS The current study used cross-sectional survey data col- lected by the Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) and the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN) [17] be- tween May and August 2007. The sample for this study was 287 individuals who indicated having being diag- nosed with a chronic illness and who are older than 60 years. The study was extracted from a larger nationally representative cross-sectional survey of 6,783 Jamaicans. The survey was drawn using stratified random sampling. This design was a two-stage stratified random sampling design where there was a Primary Sampling Unit (PSU) and a selection of dwellings from the primary units. The PSU is an Enumeration District (ED), which constitutes of a minimum of 100 dwellings in rural areas and 150 in urban areas. An ED is an independent geographic unit that shares a common boundary. This means that the country was grouped into strata of equal size based on dwellings (EDs). Based on the PSUs, a listing of all the dwellings was made, and this became the sampling frame from which a Master Sample of dwelling was compiled, which in turn provided the sampling frame for the labour force. One third of the 2007 Labour Force Survey (LFS) was selected for the Jamaican Survey of Living Conditions (JSLC, 2007) [17]. The sample was weighted to reflect the population of the nation. The researchers chose this survey based on the fact that it is the latest survey on the national population and  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 103 that it has data on the health status of Jamaicans. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect the data, which were stored and analyzed using SPSS for Windows 16.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA). The ques- tionnaire was modeled from the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) household sur- vey. There are some modifications to the LSMS, as JSLC is more focused on policy impacts. The question- naire covered areas such as socio-demographic, eco- nomic and health variables. The non-response rate for the survey was 26.2%. Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency and percentage were used to analyze the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. Chi- square was used to examine the association between non-metric variables, and an Analysis of Variance (AN- OVA) was used to test the relationships between metric and non-dichotomous categorical variables. Logistic regression examined the relationship between the de- pendent variable and some predisposed independent (explanatory) variables, because the dependent variable was a binary one (health status: 1 if reported poor health status and 0 if otherwise). The results were presented using unstandardized B-coefficients, Wald statistics, Odds ratio and confi- dence interval (95% CI). The predictive power of the model was tested using the Omnibus Test of Model and Hosmer and Lemeshow [18] was used to examine goodness of fit of the model. The correlation matrix was examined in order to ascertain whether autocorrelation (or multicollinearity) existed between variables. Based on Cohen and Holliday [19] correlation can be low (weak)—from 0 to 0.39, moderate—0.4-0.69, and strong —0.7-1.0. This was used to exclude (or allow) a variable in the model. Wald statistics were used to determine the magnitude (or contribution) of each statistically signifi- cant variable in comparison with the others, and the Od- ds Ratio (OR) for the interpreting of each significant va- riable. Multivariate regression framework was utilized to as- sess the relative importance of various demographic, socio-economic characteristics, physical environment and psychological characteristics, in determining the health status of Jamaicans; and this has also been em- ployed outside of Jamaica. This approach allowed for the analysis of a number of variables simultaneously. Secondly, the dependent variable is a binary dichoto- mous one and this statistic technique has been utilized in the past to do similar studies. Having identified the de- terminants of health status from previous studies, using logistic regression techniques, final models were built for Jamaicans as well as for each of the geographical sub-regions (rural, peri-urban and urban areas) and sex of respondents using only those predictors that inde- pendently predict the outcome. A p-value of 0.05 was used to for all tests of significance. 2.1. Model The use of multivariate analysis in the study of health and subjective wellbeing (i.e. self-reported health or happiness) is well established [20,21] and this is equally the case in Jamaica and Barbados [22,23]. The current study will employ multivariate analyses in the study of health status of elderly Jamaicans with diagnosed chronic medical conditions. The use of this approach is better than bivariate analyses as many variables can be tested simultaneously for their impact (if any) on a de- pendent variable. The current study seeks to examine the social deter- minants of poor health status of old Jamaicans who re- ported having at least one chronic medical condition (Eq.1): Ht = f(Ai, Gi, ARi, FCi, NFCi, MRi, Si, HIi, CRi, MCt, SAi, εi) (1) where Ht (self-rated current health status in time t) is a function of age of respondents, Ai ; sex of individual i, Gi; area of residence, ARi; food consumption per person per household member, FCi; non-food consumption per person per household member, NFCi; marital status of person i, MRi; social class of person i, Si ; health insur- ance coverage of person i, HIi; crowding of individual i, CRi; medical expenditure of individual i in time period t, MCt; social assistance of individual i, SAi and an error term (ie. residual error). 2.2. Measure Age is a continuous variable which is the number of years alive since birth (using last birthday). Age group is a non-binary measure: young-old (ages 60 to 74 years); old-old (ages 75 to 84 years) and oldest-old (ages 85 years and older). Elderly denotes the chronological age of 60 years and beyond. Self-reported illness (or self-reported dysfunc- tion): The question was asked: “Is this a diagnosed re- curring illness?” The answering options were: Yes, cold; Yes, diarrhoea; Yes, asthma; Yes, diabetes mellitus; Yes, hypertension; Yes, arthritis; Yes, Other; and No. A binary vari- able was later created from this construct (1 = yes, 0 = otherwise) in order to use in the logistic regression. Health status: “How is your health in general?” And the options were very good; good; fair; poor and very poor. For this study the construct was categorized into 3 groups with (i) good; (ii) fair, and (iii) poor. A binary variable was later created from this variable (1 = good and fair 0 = otherwise). Social class: This variable was measured based on in- come quintile: The upper classes were those in the weal-  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 104 Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of sample. Variable Frequency Percent Sex Men 110 38.3 Women 177 61.7 Diagnosed chronic medical condition Diabetes mellitus 73 25.4 Hypertension 124 43.2 Arthritis 38 13.2 Other (unspecified) 52 18.2 Health care-seeking behavior Sought care 201 70.8 Did not seek care 83 29.2 Why didn’t you seek care Could not afford it 14 17.7 Was not ill enough 29 36.7 Preferred home remedies 11 13.9 Didn’t have time to go 6 7.6 Unspecified 19 24.1 Purchased medication Prescribed medicine 198 72.0 Partial prescription 8 2.9 Prescribed/over the counter 6 2.2 Over counter 6 2.2 Prescribed, but did not buy 9 3.3 No 48 17.4 Health insurance coverage Private 23 8.0 Public 72 25.2 No 191 66.8 Health status Good 49 17.1 Fair 136 47.4 Poor 102 35.5 Area of residence Urban 76 26.5 Other town 55 19.1 Rural 156 54.4 Social class Poor 114 39.7 Middle 62 21.6 Wealthy 111 38.7 Household head No 85 29.6 Yes 202 70.2 thy quintiles (quintiles 4 and 5); middle class was quintile 3 and poor those in lower quintiles (quintiles 1 and 2). 3. RESULTS 3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics The sample was 287 elderly respondents (38.3% of men and 61.7% of women), with 57.1% young-old; 33.1% old-old and 9.8% oldest-old. Seventy percent of the sample was head of household; 35.5% had poor health status; 70.8% sought health care; 72.0% purchased the prescribed medication; 33.2% had public health insur- ance coverage; 39.7% were poor; 26.5% lived in urban areas, 19.2% in other towns and 54.4% in rural areas (Table 1). Majority (43.2%) of the sample reported hy- pertension; 25.4% diabetes mellitus; 13.2% rheumatoid arthritis and 18.2% unspecified the type of chronic ill- ness that they were diagnosed with (Table 1). Approxi- mately eighteen percent of those who indicated that they did not seek care indicated that they could not afford it; 36.7% indicated that they were not ill enough; 13.9% reported that they use home remedy. 3.2. Bivariate Analyses There was no statistical correlation between health status and self-reported dysfunction (χ2 = 1.810, P = 0.404, n= 286) (Table 2). Based on Table 2, only 35.4% of those who indicated that they had at least one chronic medical condition reported poor health status. Table 3 revealed a statistical relation between health status and area of Table 2. Health status by self-reported dysfunction.  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 105 Self-reported Dysfunction Health status No n (%) Yes n (%) Total n (%) Good 0 (0.0) 49 (17.2) 49 (17.1) Fair 0 (0.0) 135 (47.4) 135 (47.2) Poor 1 (100.0) 101 (35.4) 102 (35.7) Total 1 285 286 χ2 (df = 2) = 1.810, P = 0.404, n = 286 Table 3. Health status by area of residence. Area of residence Total Health status Urban Other town Rural Good 16 (21.1) 11 (20.0) 22 (14.1) 49 (17.1) Fair 42 (55.3) 29 (52.7) 65 (41.7) 136 (47.4) Poor 18 (23.7) 15 (27.3) 69 (44.2) 102 (35.5) Total 76 55 156 287 χ2 (df = 4) = 11.569, P = 0.021, n=287 Table 4. Diagnosed chronic medical condition by area of residence. Area of residence Total Diagnosed chronic medical condition Urban Other town Rural Diabetes mellitus 25 (32.9) 17 (30.9) 31 (19.9) 73 (25.4) Hypertension 25 (32.9) 22 (40.0) 77 (49.4) 124 (43.2) Rheumatoid arthritis 9 (11.8) 5 (9.1) 24 (15.4) 38 (13.2) Other (unspecified) 17 (22.4) 11 (20.0) 24 (15.4) 52 (18.1) Total 76 55 156 287 χ2 (df = 6) = 10.455, P = 0.107, n=287 Table 5. Self-reported chronic medical condition by social class. Social Class Self-reported chronic medical condition Poor Middle class Upper class Total Diabetes mellitus 21 (18.4) 11(17.7) 41 (36.9) 73 (25.4) Hypertension 55 (48.2) 32 (51.6) 37 (33.3) 124(43.2) Rheumatoid arthritis 19 (16.7) 8 (12.9) 11 (9.9) 38 (13.2) Other (unspecified) 19 (16.7) 11 (17.7) 22 (19.8) 52 (18.1) Total 114 62 111 287 χ2 (df = 6) = 15.870, P = 0.014, n=287 residence [χ2 (df = 4) = 11.569, P = 0.021, n = 287]. Ru- ral residents reported the highest poor health status (44.2%) compared to other town (27.3%) and urban area residents (23.7%). On the other hand, greatest good heal- th status was reported by urban residents (21.1%), com- pared with other town (20.0%) and rural area residents (14.1%) (Table 3). No statistical association was found between diagnosed chronic medical condition and area of residence [χ2 (df = 6) = 10.455, P = 0.107, n = 287] (Table 4). A statistical correlation was found between self-re- ported chronic medical condition and social class [χ2 (df = 6) = 15.870, P = 0.014, n = 287]. The wealthy was most likely to have diabetes mellitus (36.9%) while the poor (48.2%) and the middle class (51.6%) were mostly likely to indicated hypertension. Approximately ten per- cent of the wealthy had arthritis compared to 12.9% of middle class and 16.7% of poor (Table 5). The mean number of day reported to have illness was 71.6 days (SD = 185.1, 95% CI = 49.1 – 94.2 days). Ur- ban dwellers reported the least number of days in illness (mean = 7.5 days, SD=10.96, 95% CI = 4.7 – 10.2 days) compared to other town residents (mean = 98 days, SD = 216.4, 95% CI = 38.3 – 157.6 days) and rural residents  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 106 Table 6. Annual consumption expenditure, length of illness, total medical expenditure, public medical expenditure, private medical expenditure by area of residence. Variable Area of residence n Mean Std. Deviation 95% Confidence Interval †Annual consump- tion expenditure* Urban 76 8711.95 6761.20 716695 - 10256.95 Other Town 55 7388.90 5271.25 5963.88 - 8813.91 Rural 156 5445.09 4470.72 4738.01 - 6152.17 Total 287 6682.69 5485.63 6045.34 - 7320.03 ††Length of illness Urban 64 7.45 10.96 4.72 - 10.19 (days) Other Town 53 97.98 216.44 38.32 - 157.64 Rural 143 90.55 206.90 56.35 - 124.76 Total 260 71.61 185.10 49.01 - 94.22 †††Number of visit to health care practi- tioner Urban 55 1.65 1.58 1.23 - 2.08 Other town 39 1.21 .61 1.01 - 1.40 Rural 101 1.42 .85 1.25 - 1.58 Total 195 1.44 1.08 1.29 - 1.59 ††††Medical expen- diture* Urban 57 1481.58 1988.75 953.89 - 2009.27 Other town 39 1817.95 2377.57 1047.23 - 2588.67 Rural 103 1805.34 5154.02 798.04 - 2812.64 Total 199 1715.07 3988.73 1157.48 - 2272.67 † F statistic [2,284] = 10.248, P < 0.001; †† F statistic [2,257] = 5.031, P = 0.006; ††† F statistic [2,192] = 2.057, P = 0.131; †††† F statistic [2,196] = 0.136, P = 0.001 Table 7. Logistic regression: Predictors of poor health status of those diagnosed with chronic medical condition. Variable Coefficient Std. Error Wald statistic Odds ratio 95.0% C.I. Middle class 0.647 0.527 1.507 1.909 0.680 - 5.360 Upper class 0.427 0.639 0.446 1.533 0.438 - 5.366 †Poor Man 0.765 0.386 3.937* 1.000 2.150 1.009 - 4.578 Urban areas -0.314 0.439 0.512 0.730 0.309 - 1.727 Other towns -0.449 0.466 0.931 0.638 0.256 - 1.589 †rural areas Social assistance (1=yes) -0.112 0.461 0.059 1.000 0.894 0.362 - 2.207 Crowding 0.173 0.119 2.124 1.189 0.942 - 1.499 Age 0.033 0.022 2.182 1.033 0.989 - 1.079 Married 0.257 0.403 0.406 1.293 0.587 - 2.847 Divorced, separated or widowed 0.629 0.461 1.858 1.875 0.759 - 4.628 †Never married Non-food consumption 0.000 0.000 0.017 1.000 1.000 1.000 - 1.000 Food consumption 0.000 0.000 4.088* 1.000 1.000 - 1.000 Health insurance (1=yes) 0.390 0.382 1.039 1.476 0.698 - 3.123 χ2 (df = 13) = 20.249, P < 0.001; n = 285 -2 Log likelihood = 238.17 Nagelkerke R2 =0.115 Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2=7.565, P = 0.477 Overall correct classification = 83.5% Correct classification of cases of self-rated poor health status = 99.2% Correct classification of cases of self-rated good health status = 6.3% †Reference group *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 107 (mean = 90.6 days, SD = 206.9, 95% CI = 56.4 – 124.8 days) - F statistic [2,257] = 5.031, p = 0.006. This was similar for medical health care expenditure - F statistic [2,196] = 0.136, P = 0.001. The mean amount spent on medical care for urban residents was US $21.85 com- pared to US $26.12 for other town residents and US $26.81 for rural respondents. On the other hand, there was a statistical difference between annual consumption expenditure and area of residence - F statistic [2,284] = 10.248, P < 0.001. The mean annual amount spent by urban dwellers was US $8, 711.95 than other town dwellers US $7, 388.90 and rural residents US $5, 445.09 (Table 6). 3.3. Multivariate Analyses The socio-demographic determinants of poor health sta- tus of those who indicated being diagnosed with chronic illness were sex of respondents (OR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.009 – 4.578) and food consumption (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 1.00 – 1.00) (Table 7). Elderly men who revealed that they were diagnosed with chronic illness were 2.15 times more likely to indicated poor health than elderly women (Table 7). 4. DISCUSSION The current revealed that 43 out of every 100 elderly Jamaican who reported chronic illness had hypertension, 25 in every 100 had diabetes mellitus and 13 in every 100 had rheumatoid arthritis. Thirty-five in every 100 indicated poor self-reported health status; 70 out of every 100 were household heads; 29 out of every 100 did not seek care and of those who did not seek care 37% indicated that they were not ill enough to visit a medical practitioner or health facility. Rural residents had greatest percentage with hypertension (49.4%) and rheumatoid arthritis (15.4%) compared to other area of residents. However, urban residents had the greatest percent of diabetes mellitus (32.9%) compared to peri-urban (30.9%) and rural residents (19.9%). Upper class people recorded the most diabetes mellitus cases (37%) compared to the poor (18%) and the middle class (18%). Middle class however recorded the most hyper- tensive cases (52%) compared to the poor (48%) and the wealthy (33%). Concurrently, the poor recorded the most rheumatoid arthritis cases (17%) compared to the middle class (13%) and the wealthy (10%). Only sex and food consumption were found to be correlated with self-reported health status. Older men self-reported health status was almost 2.2 times more than that for older women, and those who consumed more food re- corded better health status. Furthermore, the duration of illness (in days) for rural residents was 12 times more than that for urban residents and their medical expendi- ture was 1.2 times more than that of those in urban areas. Concurrently, periurban residents spent 13 times more days in illness than urban residents and spent 1.2 times more on medical expenditure. Self-reported health status has been widely used in censuses, surveys, and observational studies and there is evidence suggesting that self-reported health is an indi- cator of general health with good construct validity [24] and is a respectably powerful predictor of mortality risks [25], disability [26] and morbidity [27]. The results of this study showed that the majority of those sampled re- ported themselves to be experiencing good or fair health, while approximately one-third indicated poor health. Th- ese results concur with those by other researchers from Dominica [28] and Trinidad [29]. In a recent island wide survey of persons aged 65 years and older conducted in Trinidad in 2002, 44% reported their health as fairly good or good. In reviews of the literature, Benyamini & Idler [30] and Idler & Benyamini [25], showed that in most studies conducted since the 1980s, the elderly people who self-rated their health as bad presented greater inci- dence of death than did those who considered it to be excellent. Among elderly people, self-rated health may present greater sensitivity for men than for women. Since women live longer than men and experience more years with diseases and incapacities, they tend to rate their health more negatively than do men, but do not necessar- ily die because of this, over the short term. Thus, negative self-rated health expressed by women may be more asso- ciated with quality of life. On the other hand, when men rate their health negatively, they present a greater risk of succumbing to a fatal event [31]. There has been a general epidemiological shift from infectious to chronic diseases and the elderly are one of the main at risk groups. In this study, just over one-third of the respondents who reported poor health indicated that they had at least one chronic disease. This is less than the 80% reported in a study in Trinidad [29]. The main chronic illnesses reported by the respondents in this study were hypertension, diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis. This is in keeping with the study by Rawlins et al. [29] and other Caribbean studies on this age group [32,33]. Furthermore, a study conducted on elderly Jamaicans showed that this age cohort was mainly affected by chronic non-communicable diseases [34]. The most common chronic diseases identified among the elderly in Jamaica are hypertension, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular arrest, stroke and can- cer. Patients in the 60 and over age groups accounted for 37.2% and 41.1%, respectively, of new hypertensive and diabetic cases [35]. Some gender differences have been reported in respect of chronic illnesses with women at greater risk for hypertension and men cardiovascular  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 108 diseases [36]. Furthermore, in 1991, cardiovascular dis- eases followed by diabetes mellitus and neoplasms were the diseases for which Jamaicans 65 years older were most often hospitalized [37]. Data for the Caribbean showed that hypertension and rheumatoid arthritis are morbidities that significantly affect both men and women [38]. The current study re- vealed that hypertension was the leading cause of illness among older and oldest elderly in Jamaica, followed by diabetes mellitus, and rheumatoid arthritis, which concurs somewhat with a past study [39] that had hypertension as the leading cause of morbidity of the elderly, followed by rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus. In another reported study, the most common chronic diseases identi- fied among the elderly were hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular arrest, stroke and cancer [35]. Some gender differences have been re- ported in respect of chronic illnesses with women at greater risk for hypertension and men cardiovascular diseases [36]. In a recent study by Bourne, 1.4 times more women had diabetes mellitus than men and this was the same for hypertensive older and oldest elderly Ja- maicans [39]. On the other hand, there were 1.6 times more old and oldest elderly Jamaican men with self-reported rheumatoid arthritis than women [39]. Th- ese chronic non-communicable diseases continue to in- terface within the functional lives of the elderly, which means that they are indeed living longer but are faced with lower levels of good health than young adults (ages 15 to 29 years) and middle-aged adults (ages 30 to 59 years). According to the JSLC there has been significant increase in illness/injury among older persons since 1997 [40]. Data from the 2002 survey indicate that 34.6 per- cent of the elderly population surveyed, reported an ill- ness or injury during the four-week reference period [41]. Hypertension is one of the most important treatable causes of morbidity and mortality and accounts for a large proportion of cardiovascular diseases in elderly in Jamaica [42]. It is known to be a major risk factor for the development of diabetic renal disease, and hyperglycae- mia also has a role in the development of diabetic neph- ropathy [43]. Studies from developed countries have reported prevalence of raised blood pressure among eld- erly to vary from 60% to 80% [44]. Furthermore, diabe- tes mellitus is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among persons aged 65 and older [45]. About 20% of persons in this age group are estimated to have diabetes mellitus, with another 25% in pre-diabetic stages [46]. Moreover, because diabetes can be asymp- tomatic for many years, about 50% of older individuals with diabetes are thought to be undiagnosed [47]. In Jamaica, diabetes-related deaths in 1994 had increased 147% over the 1980 level and represented the third leading cause of loss of years of potential life among women and tenth among men [48]. There is evidence that this is due to the low rates of awareness, treatment and control among patients with hypertension and dia- betes [49,50]. One of the silent illnesses which emerged from the current study is unspecified health conditions. Eight out of every 100 elderly Jamaicans who reported a chronic illness stipulated unspecified conditions. Based on cau- ses of mortality and morbidity statistics in Jamaica, the other includes heart diseases; malignant neoplasm of the prostate; malignant neoplasm of the breast; and malig- nant neoplasm of the trachea, bronchus [51,52]. Statis- tics revealed that other heart diseases, malignant neo- plasm of the breast, malignant neoplasm of the prostate and malignant neoplasm of the trachea and bronchus are among the 10 leading causes of mortality for males and/or females [51]. The prevalence of diseases in this category (i.e. unspecified condition) is greater than those with rheumatoid arthritis, and statistics have showed malignant neoplasm of the prostate is the 5 th leading cause of mortality of male 50 years and older [52]. Heart diseases and malignant neoplasm of the breast were the 6th and 7 th leading cause of death respectively among females 50 years and older [52]. The unspecified health conditions are therefore silent killer among the elderly with chronic diseases. Seventy-two percent of poverty lies in rural are com- pared to 20% in urban and 9% in peri-urban area [17], indicating that poverty is accounting for illnesses ex- perienced by rural residents as well as the length of time they spent in illness. The current study showed that length of time spent in illnesses by rural residents was 12 times more than that for those in urban area, and so jus- tifying why they spend 1.2 times more on medical care compared to urban dwellers. The typology of illness that is experienced by rural residents (i.e. hypertension) is such that they require frequent visits to health care pro- viders (i.e. doctors, nurses, pharmacists). Seemingly the afore-mentioned should be the case, but we found that there was no significant statistical difference between the number of visits made to health care providers and area of residents. Like those who were unable to attend health care during the time of illness, they were either unable to afford it (18%) or diagnosed themselves as being not ill enough (37%). Inspite of this fact, 48% of the poor eld- erly with chronic illnesses had hypertension and 18% had diabetes mellitus, which are illness which require treatment and cannot be left to prayer, faith or abstinence from medical care. Rural populations generally experience excessive de- ficiencies in healthcare access, social services and other goods and services needed for healthy living. Further- more, 23% of people from rural Jamaica who reported having a chronic medical condition were not actively engaged in seeking health care because of affordability issues, compared with 9.4% from urban areas. Urban residents consistently reported better health status than rural residents, and greater satisfaction with their health  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 109 care [53]. There was a statistical correlation between good health status and area of residence, or self-reported (chronic) recurring illness and age cohort. Furthermore, the data showed that elderly Jamaicans who dwelled in rural area had the lowest self-reported good health com- pared to those who resided in other towns and urban areas. Continuing, those who resided in urban residence reported the greatest good health status. In 1997, statis- tics from PIOJ and STATIN [54] revealed that 54.3 per- cent of elderly (ages 60 years and over) lived in rural areas. A study by Bourne [39] showed that approxi- mately 7 out of every 10 old and oldest elderly in Ja- maica lived in rural areas, compared to 6 out of 10 for those 60 years and older of the population. In addition, 20 out of every 100 Jamaicans were below the poverty line, compared to 25 out of every 100 in rural Jamaica. Given that the elderly substantially lived in rural areas and that poverty for this group was 10.2 percent [55], it is not surprising that the elderly in this area of residence had a lower level of good health status than the urban elderly in Jamaica. The wealthiest in the society are expected to experi- ence better health due to their knowledge of health risks and their access to the resources necessary to avoid such risks and treat emerging health conditions [56]. But with increasing wealth and development these has been an increase in chronic disease as lifestyle changes have had a negative impact. The studies found that there were large gaps between the mean amounts of money spend by ur- ban residents compared with their rural counterparts. Furthermore, the elderly who are wealthy were more likely to have diabetes mellitus while the poor and the middle class were more likely to report hypertension. This suggests the consumption patterns of the wealthy contribute to ill-health. Thus whereas the poor become ill due to their inability to access their basic human rights, the rich become ill as a result of their harmful consump- tion patterns. According to Sobal and Stunkard [57], in developing societies there is a higher likelihood of obe- sity among men in higher socioeconomic strata. These men are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus [58] which is increasing in the adult population. Among the demographic correlates of health is the cost of medical care. It is established that medical care [20] and cost of medical care [21] are among the social de- terminants of health. 5. CONCLUSIONS The general epidemiological shift from infectious to chronic non-communicable diseases in Jamaica puts the elderly at risk. Majority of the respondents in the sample had good or fair health, and those with poor health status were more likely to report having hypertension followed by diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis. Poor health status was more prevalent among those of lower eco- nomic status in rural areas who reported the greatest number of sick days of illness and medical health care expenditure. The prevalence of chronic diseases and lev- els of disability in older people can be reduced with ap- propriate health promotion and strategies to prevent non-communicable diseases. This research provides valuable information on health status and the non-comm- unicable diseases which affect the elderly in Jamaica, and particular socioeconomic group respond being diagnosed with particular chronic illnesses. These findings can as- sist health care professionals to specifically and adequ- ately address the health needs of the elderly in Jamaica. REFERENCES [1] United Nation Organization (2004). Country profile: Sta- tus and implementation of national policies on ageing in Jamaica. [2] Eldemire, D. (2001) Ageing—A New challenge to health care in the New Millennium. West Indian Medical J, 50, 95. [3] James, K., Eldemire, D., Gouldbourne, J. and Morris, C. (2007) Falls and fall prevention in the elderly: The Ja- maican perspective. West Indian Medical Journal, 56, 534-539. [4] Eldemire, D. (1993) An epidemiological study of the Jamaican elderly. PhD Thesis. The University of the West Indies, Jamaica. [5] Plan of Action on Health and Ageing. (1999) Older Adults in the Americas ,1992-2000, Washington, PAHO. [6] King, H, Aubert, R.E. and Herman, W.H. (1998) Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2025: prevalence, numerical es- timates, and projections. Diabetes Care, 21, 1414-1431. [7] Murray, C.L. and Lopez, A. (1996) The Global Burden of Disease, World Health Organization, Geneva. [8] Albala, C, Lebrao, M.L, Leon, D.E.M. et al. (2005) En- cuesta Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE): me- todologia de la encuesta y perfil de la población estudiada. Pam AM J Public Health, 17, 5-6. [9] Rogers, R.G. (1996) The effects of family composition, health and social support linkage on mortality. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 37, 326-328. [10] Braithwaite, S. (1990) The elderly in Barbados: problems and policies. Bull Pan Am Health Org, 24, 314-329. [11] Manton, K.G., Stallard, E. and Tolley, H.D. (1991) Lim- its to human life expectancy: evidence, prospects, and implications. Population and Development Review, 17, 603-637. [12] Suzman, R.M. Willis, D.P. and Manton, K.G. (1992) The oldest old. New York, Oxford University Press. [13] Bourne, P. (2007) Using the biopsychosocial model to evaluate the wellbeing of the Jamaican elderly. West In- dian Medical J, 56(Suppl 3), 39-40. [14] Abel-Smith, B. (1994) An introduction to health: Policy, Planning and Financing. Essex: Pearson Education. [15] Asnani, M.R., Reid, M.E., Ali, S.B, Lipps, G. and Wil- liams-Green, P. (2008) Quality of life in patients with  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 110 sickle cell disease in Jamaica: rural-urban differences. Rural and Remote Health, 8, 1-9. [16] Planning Institute of Jamaica, (PIOJ). (2005) Economic and Social Survey, 2004. Kingston: PIOJ. [17] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ & STATIN). (2003) Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions 2002. Kingston. [18] Homer, D. and Lemeshow, S. (2000) Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York. [19] Cohen, L. and Holliday, M. (1982) Statistics for Social Sciences. London, England: Harper and Row. [20] Grossman, M. (1972) The demand for health-a theoretical and empirical investigation. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. [21] Smith, J.P. and Kington, R. (1997) Demographic and economic correlates of health in old age. Demography, 34, 159-170. [22] Bourne, P.A. and McGrowder D.A. (2009) Rural health in Jamaica: examining and refining the predictive factors of good health status of rural residents. Rural and Remote Health, 9, 1116. [23] Hambleton, I.R, Clarke, K, Broome, H.L, Fraser, H.S, Brathwaite, F. and Hennis, A.J. (2005). Historical and current predictors of self-reported health status among elderly persons in Barbados. Rev Pan Salud Public, 17, 342-352. [24] Smith, J. (1994) Measuring health and economic status of older adults in developing countries. Gerontologist, 34, 491-496. [25] Idler, E.L. and Benjamin, Y. (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: A Review of Twenty-seven Community Stud- ies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21-37. [26] Idler, E.L. and Kasl, S. (1995) Self-ratings of health: Do they also predict change in functional ability? Journal of Gerontology, 50B, S344-S353. [27] Schechter, S., Beatty, P. and Willis, G.B. (1998) Asking survey respondents about health status: Judgment and response issues, In: Schwarz, N., Park, D., Knauper, B and. Sudman, S (ed.): Cognition, aging, and self-reports. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Taylor and Francis. [28] Luteijn, B. (1996) Health status of the elderly in the Marigot Health District, Dominica. West Indian Medical Journal, 45(Suppl.2), 31. [29] Rawlins, J.M, Simeon, D.T, Ramdath, D.D. and Chadee, D.D. (2008) The elderly in Trinidad: Health, social and economic status and issues of loneliness. West Indian Medical Journal, 57, 589-595. [30] Benyamini, Y. and Idler, E. (1999) Community studies reporting association between self-rated health and mor- tality: additional studies, 1995 to 1998. Res Aging, 21, 392-401. [31] Lebrao, M.L, Durate, Y.A.O, and Organizers. (2003) KNOW—Health, Wellness and Aging: the SABE project in the municipality of Sao Paulo: an approach starts Brasi- lia (DF): SABE project in the city of Sao Paulo: an initial approach. Brasília (DF): Pan American Health. Available in: http://www.opas.org.br/sistema/arquivos/l_saber.pdf [32] Eldemire, D. (2005) Ageing the reality. Chapter 2. In Morgan, Owen, Health Issues in the Caribbean. UWI Press, Jamaica. 157-77. [33] Alberts, J.F., Koopmans, P.O.C., Gerstenbluth, I. and Van der Heuvel, W.J. (1995) The health profile of Cura- cao: results from the Curacoa health study. West Indian Medical Journal, 44(Suppl. 2), 21-2. [34] World Health Organization. (2001) Regional Core Health Data System: Country Profile–Jamaica. http://www.Documents and Settings\user\Desktop\Regional Core Health Data System - Country Profile JAMAICA.mht. [35] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ & STATIN). (2004) Economic and Social Survey of Jamaica (ESSR). [36] Eldemire, D. (1995) Health care in Jamaica. World Hea- lth Forum, 16, 344-347. [37] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ & STATIN). (1995) Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions 1994. Kingston; December 1995. [38] Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute. (1999) Health of the elderly. Cajanus, 32, 217-240. [39] Bourne, P. (2009) Good health status of older and oldest elderly in Jamaica. Are there differences between rural and urban areas? Open Geriatric Medicine Journal, 2, 18-27. [40] Country profile and implementation of national policy on ageing in Jamaica. www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/workshops/Vi enna/jamaica.pdf [41] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ & STATIN). (2002) Economic and Social Survey of Jamaica, 2002. [42] Sargeant, L., Boyne, M., Bennett, F., Forrester, T., Coo- per, R. and Wilks, R. (2004) Impaired glucose regulation in adults in Jamaica: who should have the oral glucose tolerance test. Pan American Journal of Public Health, 16, 35-42. [43] Wald, H., Markowitz, H., Zevin, S. and Popovtzer, M.M. (1990) Opposite effects of diabetes on nephrotoxic and ischemic acute tubular necrosis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med, 195, 51-56. [44] Kalavathy, M.C., Thankappan, K.R., Sharma, P.S. and Vasan R.S. (2000) Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in an elderly community-based sample in Kerala, India. Natl Med J India 13: 9-15. [45] Desai, M., Zhang, P. and Hennessy, C. Surveillance for morbidity and mortality among older adults - United States 1995-1996. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48, 7-25. [46] Samos, L. and Roos, B. (1998) Diabetes mellitus in older persons. Medical Clinics of North America, 82, 791-803. [47] Meneilly, G. and Tessier, D. (2001) Diabetes in elderly adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 56A(1), M5-M13 . [48] Health Situation Trends. (1998) Situation Trends. Health in the Americas, 1988 Edition,. Washington, D.C.: PAHO. 1. [49] Wilks, R., Sargent, L.A., Guilliford, M.C., Reid, M. and Forrester, T. (2001) Quality of care of hypertension in three clinical settings in Jamaica. West Indian Med J, 49, 220-225. [50] Wilks, R.J., Sargent, L.A., Guilliford, M.C., Reid, M.E. and Forrester, T.E. (2001) Management of diabetes mel- litus in three settings in Jamaica. Rev Panam Salud Pub- lica, 9, 65-72.  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 101-111 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 111 [51] Statistical Institute of Jamaica, STATIN. Demographic statistics, 2007. Kingston; STATIN: 2008. [52] Planning Institute of Jamaica, PIOJ. Economic and So- cial Survey Jamaica, 2007. Kingston. [53] Edelman, M. and Menz, B. (1996) Selected comparisons and implications of a national rural and urban survey on health care access, demographics, and policy issues. Journal of Rural Health, 12, 197-205. [54] Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ). (2008) Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN). Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions, 2007. Kingston: PIOJ & STATIN. [55] Jamaica—medium term socioeconomic policy frame- work 2004-2007, February 2005. pioj.gov.jm/Documents/ MTPFJDP/33.pdf [56] Pimple, F. and Rogers, R. (2004) Socioeconomic Status, Smoking and Health: A Test of Competing Theories of Cumulative Advantage. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, American Sociological Association. 45(3), 306-321. [57] Sobal, J. and Stunkard A.J. (1989) Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull, 105, 260-275. [58] Astrup, A. and Finer, N. (2001) Redefining Type 2 dia- betes: Diabetes or obesity dependent diabetes. Obesity Reviews, 1, 57-59. |