Health

Vol.07 No.09(2015), Article ID:59873,16 pages

10.4236/health.2015.79131

Two NGO-Run Youth-Centers in Multicultural, Socially Deprived Suburbs in Sweden―Who Are the Participants?

Susanna Geidne*, Ingela Fredriksson, Koustuv Dalal, Charli Eriksson

School of Health and Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

Email: *susanna.geidne@oru.se, ingela.fredriksson@oru.se, koustuv.dalal@oru.se, charli.eriksson@oru.se

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 8 August 2015; accepted 21 September 2015; published 24 September 2015

ABSTRACT

Objective: Leisure-time is an important part of young people’s lives. One way to reduce social differences in health is to improve adolescents’ living conditions, for example by enhancing the quality of after-school activities. Multicultural, socially deprived suburbs have less youth participation in organized leisure-time activities. This study explores who the participants are at two NGO-run youth-centers in multicultural, socially deprived suburbs in Sweden and whether socio-demographic, health-related, and leisure-time factors affect the targeted participation. Methods: The study can be seen as an explanatory mixed-methods study where qualitative data help explain initial quantitative results. The included data are a survey with youth (n = 207), seven individual interviews with staff, and six focus-groups interviews with young people at two youth-centers in two different cities. Results and Conclusions: The participants in the youth-centers are Swedish born youths having foreign-born parents who live with both parents, often in crowded apartments with many siblings. Moreover they feel healthy, enjoy school and have good contact with their parents. It seems that strategies for recruiting youths to youth-centers have a large impact on who participates. One way to succeed in having a more equal gender and ethnicity distribution is to offer youth activities that are a natural step forward from children’s activities. The youth-centers’ proximity is also of importance for participation, in these types of neighborhoods.

Keywords:

Youth-Center, Leisure-Time, Participation, Suburbs, NGO

1. Introduction

Leisure-time is important for young people’s psychological, cognitive, and physical development [1] . Individuals outside the family become more important to adolescents, and leisure-time can therefore have a greater impact on their beliefs and behavior [2] . Most children and youth can decide how they want to spend this time, which gives the content of leisure activities an important role in youth development [3] [4] . Leisure-time also comprises a large part of young people’s lives today and differs in some ways from that of earlier generations [4] [5] . However, there is no guarantee that young people will use their leisure-time beneficially, for example by choosing activities that challenge them [6] .

Multicultural, socially deprived suburbs have less youth participation in organized leisure-time activities than other areas, due to both their higher proportion of immigrants and lower socioeconomic status (SES) [7] - [9] . Young people do not choose their leisure activities randomly; social circumstances are one of the determinants that matter [10] . Children’s activities are also often chosen by their parents [11] . One way to reduce social differences in health is to improve children’s and adolescents’ living conditions, for example by enhancing the quality of school and after-school activities [12] . Much of the variation in health among children and adolescents can be explained by social factors (cf. [13] [14] ).

Studies of adolescents’ participation in leisure-time activities often examine organized sports activities and confirm that participants to a greater extent are male and have high SES background (cf. [15] - [18] ). Adolescents who participate in both sports and other organized activities have been found less likely to use alcohol and drugs [19] . Moreover, harmful use of alcohol is less common among adolescents born outside of Sweden than adolescents born in Sweden [20] . Participation in leisure-time activities is associated with better academic achievement [21] [22] . It can be of particular significance for adolescents with lower SES [15] .

Participation in structured activities relates to low levels of antisocial behavior [23] and to having a clear idea of what to do after leaving compulsory school [24] . It seems as if it is the psychologically healthy adolescents who tend to be involved in structured activities [25] . On the other hand, participants in low-structured activities were characterized by deviant peer relations and poor relations between parents and children [23] . They also more often lived in two homes and had an unemployed mother [24] . One reason that participation in structured activities relates to good adjustment is self-selection, because well-adjusted youth choose structured activities [26] . A medium level of participation in organized leisure activities is most favorable for adolescents’ health and well-being [24] . Youth-centers are often less structured than organized sports and other leisure-time activities. However, they have opportunities to reach youth who are not interested in sports or other leisure activities.

Leisure-time activities for adolescents are constituted differently in different parts of the world. In countries like USA, extracurricular activities and out-of-school time [27] are two concepts. In Sweden, two orientations can be identified as important. On the one hand there is the widespread tradition of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which run leisure-time activities, for example within sports. On the other hand, there are youth- centers, which are often run by municipalities.

Leisure-time is an important part of adolescents’ lives. Leisure-time activities can be beneficial to young people’s development. However, young people, especially girls, living in multicultural, socially deprived suburbs participate less in leisure-time activities. There is a need to understand who the participants are to be able to develop youth-centers in these neighborhoods. Youth-centers located in these neighborhoods can be a way to get young people to participate in leisure-time activities. Therefore this study has aimed to explore who participate in two NGO-run youth-centers in multicultural, socially deprived suburbs in Sweden with special focus on socio-demographic factors, health-related factors, or leisure-time factors.

2. Methods

This study is part of a study focusing on “Leisure-time as a setting for alcohol and drug prevention” in a special venture financed by the Swedish government [28] . The research program will answer a series of questions as why do young people participate in this type of activity and what particular strategies do the different youth- centers use in their everyday work. A three year longitudinal study will also try to answer the question what the young people gain from being participants in youth-center activities, The study was approved by the regional ethical committee in Uppsala in January 2012 (reg. No. 2011/475).

This study can be seen as an explanatory mixed-methods study, using Creswell and Plano Clark’s approach [29] , whereby qualitative data helps to explain initial quantitative results. Data were collected at the two youth- centers using surveys, individual interviews, and focus-groups interviews.

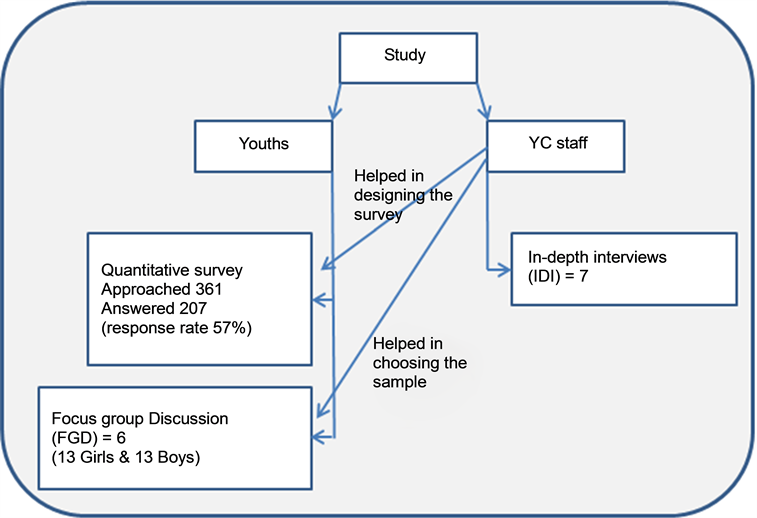

The study has also used a participatory and practice-based approach. This involves cooperating with youth- center staff on survey questions, data collection procedures, and samples (Figure 1). It also includes regular feedback to the youth-centers within six months after data collection, as well as extra feedback upon request. This approach was chosen for two reasons: (1) people are experts on their own settings, and (2) it is of great importance that the research results be of practical use for the setting, in this case the youth-centers.

2.1. The Study Context

The two youth-centers in this study are located in suburbs in two of the top-ten cities (by population) in Sweden. Both of these suburbs are characterized by apartment blocks and a high proportion of residents with immigrant backgrounds (60% - 90% compared with 20% for Sweden as a whole). The most frequent countries of origin are Iraq and Somalia [30] . The youth-centers are run by two different NGOs. The first, hereafter called T, is located in the neighborhood’s central shopping area. T’s activities cater to young people in the area aged 12 - 16 years. The second NGO, hereafter called V, has two different premises, one for youth up to 13, and another for youth between 13 and 18 years. Both youth-centers provide structured activities, such as dance groups, travel groups, tutoring, exhibitions, and leadership training, as well as unstructured activities, such as playing games, watching television, or just hanging out with friends. The youth-centers have both paid and volunteer staff. The paid staffs have educational training and the volunteer staffs are older youth, former participants, with internal leadership training. T primarily has employed leaders. V has few employed leaders, but many volunteer youth leaders.

2.2. Sample

The study used purposive sampling; those who came to the youth-centers during a defined time period were invited to take part, the idea being to reach people in voluntary and partly unstructured activities. Both youth- centers are member-based, and lists of all members in the targeted age group (12 - 16 years) were provided by each youth-center (Table 1). Since not all members visited the youth-centers on a regular basis, we chose to use the member lists to broaden the sample as much as possible.

Parents of youth who had not reached 15 years of age (62% of the sample) received information about the study. Due to the high proportion of immigrants, information was sent in five different languages: Swedish, English, Turkish, Arabic, and Somali. The choice of languages was decided in cooperation with the staff at each youth-center. Parent could refuse consent by returning a form stating that they did not want their child to participate (5% did so).

Figure 1. Samples and data collection with a participatory approach.

Table 1. Demographic factors of the respondents.

Staff members were instructed by the researchers to choose youth of different ages for the youth focus-groups. There was to be one group of girls and one of boys per youth-center location, i.e. three groups of girls and three groups of boys in total. (One center had two separate premises.) Center staff recommended that the groups be homogenous with regard to gender instead of age. The focus-groups contained three to five members. The sample for individual interviews was decided jointly by researchers and staff, but was to include both paid and volunteer staff as well as both genders. In total seven staff members, either paid or volunteers, were interviewed.

2.3. Data Collection

Data was collected through a survey in spring 2012. The questionnaires were distributed by the center leaders during a period of six weeks at V and 10 weeks (not open on weekends) at T. The young people who voluntarily visited the centers during this time were requested to fill in the questionnaires on the premises. The length of the data collection was decided upon together with the staff of the youth-centers in order to reach as many participants as possible.

The in-depth interviews of the staff were conducted by SG and IF in all but two cases. Two interviews were conducted by IF alone. Focus-group interviews were conducted by SG or IF at the premises. The interviews were conducted in February 2013, recorded with the permission of the respondents, and then transcribed verbatim. Both in-depth interviews and focus-group interviews lasted for around an hour each.

No individuals were paid for their participation, but the youth-centers received a small sum depending on the young people’s level of participation.

2.4. Questionnaire

The questions used in this particular analysis concerned the three categories: the young person’s socioeconomic background, health-related factors such as alcohol and tobacco use, and leisure-time interests and habits (thorough described in Tables 2-6). Many of the questions have previously been used in earlier studies (cf. [31] [32] ).

2.5. Interview Guide

The semi-structured interview guide included questions about who participates and why they participate in youth-center activities. It also focused on what the young people gained, and what particular strategies the different youth-centers use in their everyday work. The questions specifically focusing on who participates concerned age, gender and birth countries. But also questions on other leisure-time interests, frequency of attendance, who stays and who drops out, and if who participates differ from year to year. The same interview guide was used for both in-depth interviews and focus-group interviews.

2.6. Analysis

2.6.1. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were employed using chi-square tests to find out if there were any differences between gender or frequency of attendance and the independent variables. Logistic regression analyses were conducted with the dependent variable gender. First, unadjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were estimated for all independent variables. Then three different logistic regression analyses were performed using three categories of independent variables (socio-demographic, health-related, and leisure-time factors). Only individuals with full information for all variables were included in the logistic regression analyses. It was not possible to enter all variables in all categories into the same model due to the low number of participants in relation to the large number of variables.

2.6.2. Qualitative Analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. An inductive qualitative content analysis was performed to analyze both the in-depth interviews and the focus-group interviews and describe variations by identifying differences and similarities in the interviews [33] .

Each interview, in its entirety, was used as a units of analysis. Meaning units were first identified in accordance with the study aim of who participates and then condensed. The condensed meaning units were then abstracted into codes. Interviews were jointly analyzed into codes from whole units of analysis by two authors (SG and IF). In moving from codes to categories, other researchers were involved to validate and discuss the results and together create categories. The codes were color-marked concerning which youth-center the respondents belonged to and whether the respondents were staff, female adolescents or male adolescents to be able to see if any categories were shared by all groups or were unique to a specific group.

3. Results

3.1. Who Are the Participants?

The survey includes 207 youth, 57% boys and 43% girls. Most participants come from youth-center V (70%, Table 1). The gender distribution is similar, but there are a higher proportion of younger participants in the sample from youth-center V.

However, the young people from the two youth-centers share many features. The majority was born in Sweden, but have foreign-born parents. Most of them live with both their parents and have fathers who work. They feel healthy, enjoy school, and feel quite safe in their neighborhoods. Almost none of them use tobacco and a small proportion has tried alcohol. Their parents know what they do in their leisure-time.

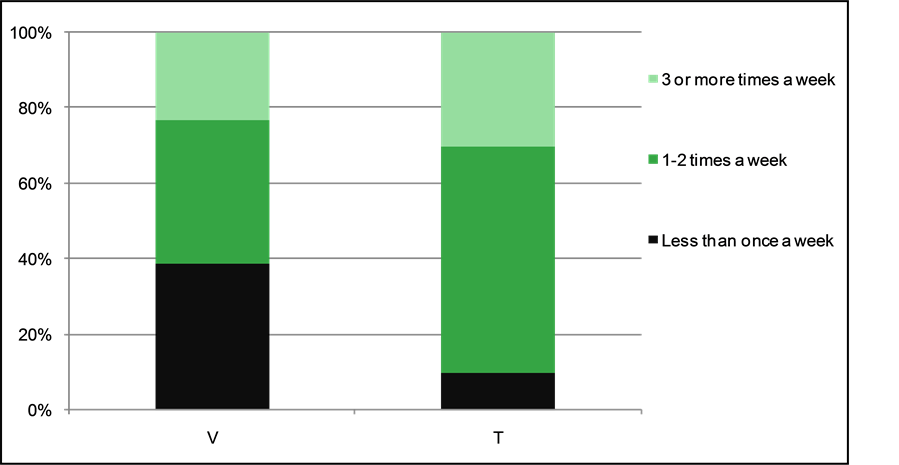

There are also some differences worth noticing between the adolescents at the two youth-centers. At V there is a higher proportion of youth who were born in Sweden, but a lower proportion whose parents were born in Sweden or Europe. At V there are also more young people who live with both parents and fewer who live in a rented apartment. More of the youth at V also have mothers who work and they enjoy school to a greater extent. Almost everyone at T lives within walking or biking distance of the youth-center; at V more than a third live farther away. The young people’s frequency of attendance has significantly different distributions at the two youth-centers (Figure 2). At V more than one third of the adolescents participate less than once a week, compared to one tenth at T.

Figure 2. Frequency of attendance at the two youth-centers (in percent) n = 181.

3.2. Are There Gender Differences?

Concerning socio-demographic factors, more girls than boys have fathers born in Sweden and live in an owned residence. Regarding health-related factors, the girls agree to a greater extent that they feel safe in their neighborhood during daytime. A higher proportion of the boys exercise more than once a week, and they are also members of a sports club to a greater extent than the girls. Other leisure-time factors that differ are that girls visit friends at home more often in the evenings, and more of them use computers more than four hours a day. The girls state to a greater extent that their parents know what they are doing in their leisure-time (Table 2).

The socio-demographic factors that remain significant after controlling for the other socio-demographic factors in a logistic regression (Table 3) are that girls are more likely to have a father born in Sweden (OR = 5.1) and to live in an owned residence (OR = 2.5). There were difference between girls and boys with regard to health-rated factors (Table 4). Girls were more likely to exercise infrequently (OR = 2.6) and were more likely to feel safe in their neighborhood during daytime (OR = 0.2). The only leisure-time factor that remains significant when controlling for other leisure-time factors is that girls to a lesser extent than boys are members of sports clubs (OR = 14.7, Table 5).

Table 2. All independent variables compared between girls and boys (in %) with chi square tests.

Table 3. Unadjusted odds ratios and all socio-demographic factors entered (CI 95%).

*Reference category: Boys.

Table 4. Unadjusted odds ratios and all health-related factors entered (CI 95%).

*Reference category: Boys.

3.3. Are There Differences between Participants’ Frequency of Attendance?

Concerning socio-demographic factors, the chi-square test (Table 6) shows that a greater proportion of the young people who participate less than once a week live in an owned residence and have a father who works than those who participate more often. The more often the young people attend the youth-center, the better they seem to rate their health. Those who are at the center often have most of their friends there and live nearby to a greater extent.

3.4. Who Participates at the Youth-Centers According to the Interviews?

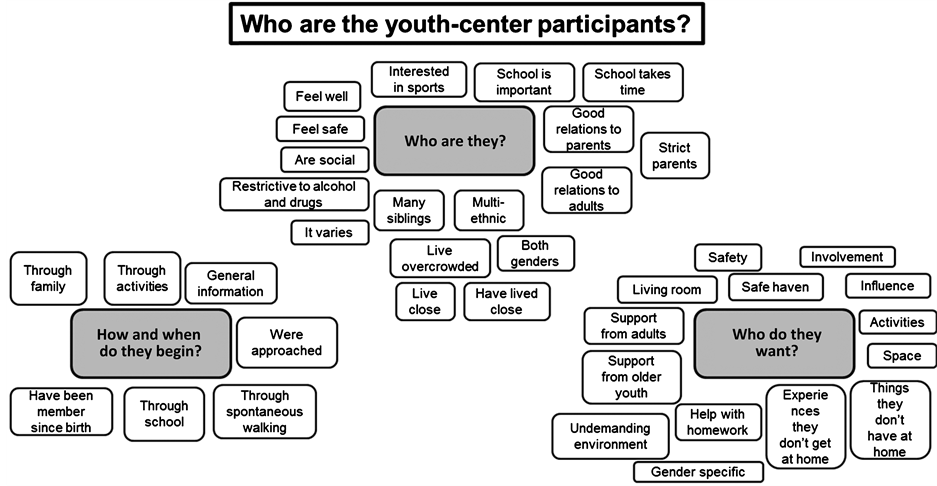

The content analysis of qualitative data collected at the two youth-centers resulted in three themes (Figure 3) which support the results of the survey on some issues and deepen and widen the understanding of some issues.

Table 5. Unadjusted odds ratios and all leisure-time factors entered (CI 95%).

*Reference category: Boys.

Table 6. All independent variables compared between three levels of frequency of attendance (in%) with chi square tests.

Figure 3. The themes and categories from the qualitative content analysis.

3.4.1. Who Are They?

Many of the youth at both centers come from families with lower SES, and many of them live in crowded apartments with many siblings. They do not attend activities in the city center, where their parents would have to drive them. However most of the young people have good home conditions and enjoy spending time with their families.

They aren’t able to spend time together at home. It’s crowded; they have many siblings. (Staff, T)

They feel comfortable in their homes. They enjoy the company of their parents. Sometimes they think their parents are too strict, but don’t almost all young people think that at that age? (Staff, V)

They respect adults and see no problems with adults being present during different activities. Most of the young people are against alcohol, tobacco, and drugs and most abstain completely. Sport is an interest mentioned by many young people at both youth-centers.

And then you’ll skip everything bad, like alcohol, cigarettes, and stuff. Instead of partying on a Friday, you can just come to the center and be with your friends, play FIFA and stuff. (Boy, T)

Especially the boys are members of sport clubs; the girls used to be members, but nowadays they often mention that schoolwork takes a lot of time. Many of the girls find it more difficult to hang out at the center and participate in various activities for reasons related to cultural gender norms.

At both youth-centers many respondents report feeling unsafe in the neighborhood. It is common for the young people accompany each other home from the center in the evenings. The young people feel safe at the centers; the older they are the safer they feel. At V there is no difference between girls’ and boys’ feeling of safety. But at T boys seem to feel safer than girls.

Or if some girl from the youth-center is going home, one of us can follow her home. Yes, we usually do. Everyone helps like that. (Boys, V)

At V boys and girls hang out more together. They sit and talk, relax, and watch television or films together, although at T it is more common that girls attend structured activities such as dance, while boys play indoor-football, FIFA (PlayStation), or hang out. At both T and V boys are at the center on weekdays more often than girls. At V they think that all the young people are nice and social, consider everyone friends, and hang out with each other even outside V. At T they think that friends are important and they often come together with friends.

Right now there are very few girls. It shifts a bit, but right now it’s like that. And the girls come for directed activities more than perhaps ten years ago. (Staff, T)

They have more boys’ activities, more boys’ games; it’s always FIFA and PlayStation and such, which are not girls’ activities; that’s a reason why girls don’t come; we’re more interested in beauty, nails, and such, but it’s only on girls’ evenings that they do that. (Girls, T)

3.4.2. How and When Do They Begin?

How and when the youth start coming to the centers differs quite a lot. Most of the young people at V have been members and have come to the center’s different premises since childhood. They start coming because they had family members and friends there. At T they start to come in grades 6 - 7, and most have been members for 2 - 4 years.

Many have grown up with this; many are members since birth. It’s like a second home. (Staff, V)

…the youth who come here now are not…it’s different now than 10 - 15 years ago when everyone went to the same school and were in the same classes. Everyone knew everyone, even before they came to us. Now they might know each other, because they live in the same area, but they’re not so closely knit and they don’t bump into each other every day, because they go to different schools and are in different classes. (Staff, T)

Visiting nearby schools is used as a way of recruiting members to both V and T. At V another active strategy is to take spontaneous walks in the neighborhood.

We usually walk around, spontaneous walks, three or four of us. We may meet some people we know; they have hardly anything to do. We talk to them about V. Tell them it’s a place where you can spend time, especially in the winter when it’s cold outside. That’s one way to spread the message. (Staff, V)

3.4.3. What Do They Want?

The young people want things they don’t have at home or experiences they don’t get at home.

…if it weren’t for V I wouldn’t, I’d never go to Dalarna and, like, be there for a week and stay in a cabin. There are such things, experiences; this activity has given me experiences that I otherwise would never get to do (Girls, V)

Not everyone has the resources. For example TV-games, Ping-Pong tables, and so on. You don’t have room for that in an apartment. (Staff, T)

Young people at both V and T talk about having a living room. A place where there is space for friends and where the environment is safe and undemanding. They also want adults to help them with homework, or just be there to talk to. At V they also emphasize the support from older youth.

Sometimes you need peace and quiet and so on. But V is like my second home; I can come here with only pants, a cardigan, newly awake―and just be here. (Girls, V)

The young people at V want to have influence and participate in decisions. Those who attend more often seem to take more responsibility. Girls show more engagement in different activities and take more responsibility. At T, some youth want to do this more than others, and the difference between genders is especially distinct. Not everyone is interested in taking responsibility and working for something they want. Some mention that they are in need of activities free from demands and obligations.

4. Discussion

This has been an explorative study. It fills a gap in the knowledge regarding who participates in NGO-run youth-centers in multicultural, socially deprived suburbs in Sweden.

Compared to a representative sample of Swedish youth, the participants in this study perceive their health as at least as good and see themselves as exercising a bit less, enjoying school a bit more, and being about as good at school as their classmates [12] . The youth also state that their parents know about their leisure activities and that they have a nice family environment. It is also an interesting finding of the study that the young people participating in the centers’ activities do not use tobacco, and few have tried alcohol. Many of them state in the questionnaire that they feel safe in their neighborhood, especially girls. In the interviews, however, they talk about the unsafe neighborhood they live in, but it is also clear that they know how to handle the situation by accompanying each other home, as an example. Earlier studies by Persson, Kerr, and Stattin [34] and Mahoney and Stattin [23] showed a concentration of problem youth with poor relations with their parents in low-structured activities like Swedish youth-centers. In this study we find quite the opposite. Holder and colleagues [11] conclude that parents choose their children’s leisure activities. It is hard to say if this is the case for these youth, but especially youth-center V has the policy always to meet with the parents of participants, unless staffs already have been in natural contact with the parents because they accompanied the participant as a young child. Some parents, especially of girls within certain ethnic groups, demand to meet the center leaders before allowing their children to participate. At youth-center T there is a pronounced trend that girls participate in structured activities and boys in unstructured activities. One explanation is that girls have fewer leisure activities overall, both because they think their schoolwork takes more time and because spending time with their families was important to them, which is in line with the study reported by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [35] . In the past almost everyone was involved in sports, but now the girls in particular are not involved anymore. At T the unstructured activities seems to attract boys more, as Lindström and Öqvist [17] also concluded.

Youth-centers help young people who live nearby to participate in leisure activities. In these multi-cultural, socially deprived suburbs, young people often live together with many siblings and family members, and lack personal space. It is also mentioned that their parents do not give them rides into town to participate in other leisure-time activities―in this case for reasons of SES, e.g. having irregular working hours or not owning a car, rather than being uninvolved parents. The youth-centers offer the young people a sense of being in a place made for their own leisure activities, and often provide a living-room atmosphere. Immigrant youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods perceive their schools as safe havens more than youths in advantaged neighborhoods [36] . In this study the youth in the same type of neighborhoods enjoy school as well, but also see their youth center as a safe haven.

Knowledge that was added from the interviews was that youth-centers’ strategies for recruiting seems to have a large impact on who participates. Youth-center V, whose members often get involved in early childhood by coming with their parents, becomes part of the both boys’ and girls’ everyday life, and members view each other as friends or even family. At youth-center T, however, which involves youth from 12 years and up, it is more important that you bring your friends (often same sex) instead of considering everyone there to be your friends already. This makes youth-center T more sensitive to trends, causing it to attract different groups (gender or ethnicity) over time as friends become more important in early adolescence than they were in childhood [2] . It seems like the group of youth who visit youth-center V less than once a week are a special group when it comes to, for example, SES. They often live in another part of town and less often in a rented apartment. The young people at V who only come for weekend or holiday activities used to live close to the center or have friends who do so. At youth-center T there are few youth who visit less than once a week, but then the center does not offer weekend or holiday activities. Hertting and Kostenius [24] conclude that the adolescents who participated in organized leisure activities less than once a week were the most vulnerable from a socioeconomic perspective. This is not the case in our study, however this type of activity cannot strictly be regarded as organized leisure activity. The youth in our study are probably more socioeconomically vulnerable than Swedish youth in general.

Methodological Discussion

As in all studies we are struggling with some limitations. Collecting data from youth participating in a voluntary, partly unstructured activity can be tricky. Our approach was to get as many respondents as possible from the two participating youth-centers; therefore we set quite a long period for data collection. The data is self-reported and cross-sectional, which means that no causal relationships can be determined. However we think that the samples are representative of the participants at the youth-centers, because a quite large proportion of the regularly visiting youth took part. Due to some internal loss, only individuals with full information for all variables were included in the logistic regression analysis (not the unadjusted odds ratios), which affected the construction of models. We argue that the study’s explorative character justifies including the large number of variables in the analysis. We are aware of the mass significance issue, which could make 5% of our tests significant although they were not.

One could discuss whether the focus-groups gave more or less information than individual interviews [37] . We argue that interaction between participants provided breadth in the answers, and that it was a cost-effective form of data collection. Interpreting interviews requires knowledge of the context in which a study is conducted [33] . The interviewers in this study were also the ones who analyzed the interviews and who analyzed the questionnaires. A strength is that staff and youth had concordant views on who participated at their youth-centers.

5. Conclusion

The participants in the youth-centers are Swedish born youths having foreign-born parents who live with both parents, often in crowded apartments with many siblings. Moreover they feel healthy, enjoy school and have good contact with their parents. It seems that strategies for recruiting youths to youth-centers have a large impact on who participate. One way to succeed in having a more equal gender and ethnicity distribution is to offer youth activities that are a natural step forward from children’s activities. The youth-centers’ proximity is also of importance for participation, in these types of neighborhoods. Good contact with parents is important for every youth activity, but is even more important to get youth to participate in a neighborhood with many immigrants with diverse views of society’s institutions. Maintaining good contact with parents can also indirectly affect parents’ networks and well-being.

Acknowledgements

The study could not have been conducted without the engaged and interested staff and young people at the two youth-centers.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Funding

The research was funded by a grant from the Swedish Public Health Agency.

Cite this paper

SusannaGeidne,IngelaFredriksson,KoustuvDalal,CharliEriksson, (2015) Two NGO-Run Youth-Centers in Multicultural, Socially Deprived Suburbs in Sweden—Who Are the Participants?. Health,07,1158-1174. doi: 10.4236/health.2015.79131

References

- 1. United Nations (2003) World Youth Report 2003. The Global Situation of Young People.

- 2. Wiium, N. and Wold, B. (2009) An Ecological System Approach to Adolescent Smoking Behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1351-1363.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9349-9 - 3. Persson, A. (2006) Leisure in Adolescence: Youths’ Activity Choices and Why They Are Linked to Problems for Some and Not Others. Orebro University, Orebro.

- 4. Zick, C.D. (2010) The Shifting Balance of Adolescent Time Use. Youth & Society, 41, 569-596.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09338506 - 5. Lehdonvirta, V. and Rasanen, P. (2010) How Do Young People Identify with Online and Offline Peer Groups? A Comparison between UK, Spain and Japan. Journal of Youth Studies, 14, 91-108.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.506530 - 6. Larson, R.W. and Verma, S. (1999) How Children and Adolescents Spend Time across the World: Work, Play, and Developmental Opportunities. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 701-36.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.701 - 7. Reardon-Anderson, J., Capps, R. and Fix, M.E. (2002) The Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families. The Urban Institute, Series B, No. B-52.

- 8. Sletten, M.A. (2010) Social Costs of Poverty; Leisure Time Socializing and the Subjective Experience of Social Isolation among 13-16-year-old Norwegians. Journal of Youth Studies, 13, 291-315.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676260903520894 - 9. Statstics Sweden (2009) Barn i dag—En beskrivning av barns villkor med Barnkonventionen som utgangspunkt.

- 10. Eriksson, L. and Bremberg, S. (2009) Fritidsaktiviteter bland unga—Halsoeffekter. Swedish National Institute of Public Health, Stockholm.

- 11. Holder, M.D., Coleman, B. and Sehn, Z.L. (2009) The Contribution of Active and Passive Leisure to Children’s Well-Being. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 378-386.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105308101676 - 12. Swedish National Institute of Public Health (2011) Svenska skolbarns halsovanor 2009/10. Grundrapport, Stockholm.

- 13. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008) Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Geneva.

- 14. Swedish National Institute of Public Health (2011) Social Health Inequalities in Swedish Children and Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Second Edition, Stockholm.

- 15. Blomfield, C.J. and Barber, B.L. (2011) Developmental Experiences during Extracurricular Activities and Australian Adolescents’ Self-Concept: Particularly Important for Youth from Disadvantaged Schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 582-594.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9563-0 - 16. Feldman, A.F. and Matjasko, J.L. (2007) Profiles and Portfolios of Adolescent School-Based Extracurricular Activity Participation. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 313-332.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.03.004 - 17. Lindstrom, L. and Oqvist, A. (2013) Assessing the Meeting Places of Youth for Citizenship and Socialization. International Journal of Social Science & Education, 3, 446-462.

- 18. Swedish National Board for Youth Affairs (2005) Unga och foreningsidrotten. En studie om foreningsidrottens plats, betydelser och konsekvenser i ungas liv. Stockholm.

- 19. Thorlindsson, T. and Bernburg, J.G. (2006) Peer Groups and Substance Use: Examining the Direct and Interactive Effect of Leisure Activity. Adolescence, 41, 321-339.

- 20. Swedish National Institute of Public Health (2013) Barn och unga 2013—utvecklingen av faktorer som paverkar halsan och genomfarda atgarder. Stockholm.

- 21. Eccles, J.S., Barber, B.L., Stone, M. and Hunt, J. (2003) Extracurricular Activities and Adolescent Development. Journal of Social Issues, 59, 865-889.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x - 22. Simpkins, S.D., Ripke, M., Huston, A.C. and Eccles, J.S. (2005) Predicting Participation and Outcomes in Out-of-School Activities: Similarities and Differences across Social Ecologies. New Directions for Youth Development, 2005, 51-69.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/yd.107 - 23. Mahoney, J.L. and Stattin, H. (2000) Leisure Activities and Adolescent Antisocial Behavior: The Role of Structure and Social Context. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 113-127.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0302 - 24. Hertting, K. and Kostenius, C. (2012) Organized Leisure Activities and Well-Being: Children Getting It Just Right! The Cyber Journal of Applied Leisure and Recreation Research, 15, 13-28.

- 25. Trainor, S.J., Delfabbro, P.H., Anderson, S. and Winefield, A.H. (2010) Leisure Activities and Adolescent Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 173-186.

- 26. Persson, A., Kerr, M. and Stattin, H. (2007) Staying in or Moving Away from Structured Activities: Explanations Involving Parents and Peers. Developmental Psychology, 43, 197-207.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.197 - 27. Weiss, H.B., Little, P.M.D. and Bouffard, S.M. (2005) More than Just Being There: Balancing the Participation Equation. New Directions for Youth Development, 2005, 15-31.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/yd.105 - 28. Eriksson, C., Geidne, S., Larsson, M. and Pettersson, C. (2011) A Research Strategy Case Study of Alcohol and Drug Prevention by Non-Governmental Organizations in Sweden 2003-2009. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6, 8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1747-597x-6-8 - 29. Creswell, J.W. and Plano Clark, V.L. (2007) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications, Thousands Oaks.

- 30. Statstics Sweden (2013) Vart femte barn har utlandsk bakgrund 2013.

- 31. Brunnberg, E., Lindèn Bostrom, M. and Berglund, M. (2008) Self-Rated Mental Health, School Adjustment, and Substance Use in Hard-of-Hearing Adolescents. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13, 324-335.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enm062 - 32. Brunnberg, E., Lindén-Bostrom, M. and Berglund, M. (2008) Tinnitus and Hearing Loss in 15-16-Year-Old Students: Mental Health Symptoms, Substance Use, and Exposure in School. International Journal of Audiology, 47, 688-694.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14992020802233915 - 33. Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 - 34. Persson, A., Kerr, M. and Stattin, H. (2004) Why a Leisure Context Is Linked to Norm-Breaking for Some Girls and Not Others: Personality Characteristics and Parent-Child Relations as Explanations. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 583- 598.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.008 - 35. Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (2007) Frihet och ansvar. En undersokning om gymnasieungdomars upplevda frihet att sjalva bestamma aver sina liv.

- 36. Svensson, Y. (2012) Embedded in a Context: The Adaptation of Immigrant Youth. Orebro University, Orebro.

- 37. Eriksson, C.-G. (1988) Focus Groups and Other Methods for Increased Effectiveness of Community Intervention—A Review. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 1, 73-80.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.