Health

Vol.5 No.3A(2013), Article ID:29603,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.53A079

What are college students saying about psychiatric medication?

![]()

1San Diego Academic Center, School of Social Work, University of Southern California, San Diego, USA; *Corresponding Author: kranke@usc.edu, dakranke@gmail.com; sallyjackson1980@gmail.com

2Rutgers School of Social Work, New Brunswick, USA; jfloersch@ssw.rutgers.edu

3Center for Culture and Health at UCLA, Department of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, USA; eileen.anderson-fye@case.edu

Received 8 January 2013; revised 15 February 2013; accepted 28 February 2013

Keywords: College Students; Mental Health; Medication; Qualitative

ABSTRACT

The number of college students who take psychiatric medication has dramatically increased. These students may be at risk for negative mental health outcomes because research shows that mental illness can delay the attainment of developmental milestones critical to adulthood. This article explores college students’ experience with psychiatric medication and how it impacts functioning and stigma. Perceptions of medication treatment could be crucial to understanding the factors that enable college students with mental illness to thrive in a university setting. Seventeen undergraduate college students in a private, Midwestern university who had a psychiatric illness and were taking prescribed psychiatric medication, were enrolled. A semi-structured interview queried college students about their perceptions of taking psychiatric medications and how the use of medication influences their functioning. Authors conducted thematic analysis by using the constant comparative method for coding data and sorting invivo codes by shared theme. Respondents generally reported positive attitudes toward medication and minimal stigma. Particular themes included: higher functioning; mitigation of symptoms; willingness to disclose; and positive longterm outlook regarding the use of medication. Students were empowered by their treatment because it positively impacted functioning and integration into the college setting. However, in contrast to the majority of study participants, one minority student reported experiencing significant external and internal stigma due to her use of psychiatric medication. Although the study’s qualitative nature, small sample size, and lack of ethnic diversity of respondents limit generalizability, important preliminary findings indicate that some college students are benefiting from the use of psychiatric medication with minimal stigma. More research is needed on college students’ experience of psychiatric medication, particularly the experience of minority students, since extant literature indicates their reluctance to utilize psychiatric medications, and a tendency toward negative perceptions of helpseeking for mental illness.

1. INTRODUCTION

The number of college students who take psychiatric medication for a mental illness diagnosis has dramatically increased [1], particularly since the rate of college students who meet the criteria for a DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) diagnosis is more now than ever, as high as 45% [2]. College students with mental health disorders constitute a vulnerable population because they are at greater risk than other college students for negative outcomes. In particular, their mental illness may delay developmental milestones critical to adulthood [3], such as forming an identity, developing intimate relationships, beginning the course of their career path, and ultimately becoming financially independent [4]. In addition, college students with mental illness tend to underperform, academically, compared with their peers [5]. Indeed, there is much at stake for this population, as a mental illness can alter their long-term goals, independence and life trajectory.

The use of psychiatric medication can be stigmatizing because it conveys social information [6] that marks some as “psychiatric patients”, which opens up the social space for others to react in a negative manner [7]. Stigma often results in consumers being denied rightful opportunities by acts of public prejudice, which can reduce functioning and recovery from a mental illness. Stigma is defined as “the identification of differentness, the construction of stereotypes, the separations of labeled persons into distinct categories and the full execution of disapproval, rejection, exclusion and discrimination” [8]. In addition, some people with mental illness may selfstigmatize, which is the internalization of rejection. As a result, these consumers endorse the negative perceptions of society, and disengage or withdraw from relationships and meaningful opportunities [9]. Ultimately, stigma can decimate life satisfaction of people with mental illness by reducing opportunities. The extant literature indicates variability in stigma experience among different age groups, particularly adolescents and adults [10]. Minimal work examines the lived experience of stigma among college students. This population may have unique experiences since they are emerging into adulthood and managing their mental health treatment. Therefore, examining the age group that bridges the developmental phases of adolescence with adulthood may yield findings that contribute to a better understanding of the different ways in which youth and adults experience stigma and why variability exists.

Race and ethnicity are also contributing factors to the experience of mental health stigma. Scholarship in this area [11-14] indicates that compared to Whites, African Americans, Hispanics and Asian Americans have more negative views toward psychiatric services and medication. Many of these negative perceptions are attributed to mistrust with the system, as well as a lack of cultural competence among mental health professionals [15]. Furthermore, these negative perceptions are passed down to younger generations [12]. However, research targeting college age minority students with mental illness is scarce. This population could have more favorable perceptions of psychiatric medication and mental health treatment than those typically held by individuals from minority groups because they are becoming more autonomous and independent from family [16]. In addition, these minority students are being exposed to mainstream cultural values within a higher educational system that places importance on providing services and treatment for mental illness.

It is important to recognize that not all individuals with mental illness internalize stigma, rather, some become empowered [9]. Research conceptualizes empowerment as the opposite of self-stigma [17]. Furthermore, “Empowerment processes are the mechanisms through which people…gain mastery and control over issues that concern them…and participate in decisions that affect their lives” [18]. Indeed, consumers that become empowered are often motivated by stigma to overcome negative treatment, lowered expectations and reduced opportunities [19]. Ultimately, empowerment can increase participation in meaningful activities, self-esteem and quality of life [20].

Purpose of Study

Limited work has examined college student attitudes surrounding the use of psychiatric medication. One such study found that perceived stigma did not pose a significant barrier to mental health care [21]. The specific aim of this article is to report preliminary findings that explore college students’ experience taking psychiatric medication, and how medication impacts their functioning and views of stigma. Perceptions of medication treatment could be crucial to understanding the factors that enable college students with mental illness to make use of psychiatric treatment which can help them succeed in a university setting.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample Recruitment

The data for this qualitative analysis come from a larger mixed method, IRB-approved (Institutional Review Board) study of college students at a competitive, urban, private Midwestern university. Students were contacted (Fall 2008) through an online survey sent to all undergraduates about perceptions of mental health services. Although more than 100 undergraduate students responded, a total of 86 of these undergraduate students completely finished the online survey. At the end of the survey, respondents could consent to be contacted for enrollment into the qualitative portion of the study. Eligibility for the qualitative study was based on the following criteria: 1) be an undergraduate student attending the university where the study was being conducted; 2) be between the ages of 18 - 25; 3) self-report to currently taking psychiatric medication. Participants were excluded from the qualitative study if they had been diagnosed with any of the following: seizure disorder; developmental disability; head injury with loss of consciousness; or brain tumor. Altogether, 17 undergraduate students were re-contacted and were qualified to take part in the study. These students were informed that the goal of the research was to obtain longitudinal, narrative data about their experience utilizing college mental health services. Respondents were interviewed once per semester for four semesters. All participants were currently prescribed and self-reported adherence to at least one psychiatric medication. The research participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. The data in this study are drawn from the first, indepth (90 - 120 minutes) interview.

2.2. Sample Demographics

Of the total 17 undergraduate college students enrolled in this qualitative study, the average age was slightly more than 19 years and ranged between 18 - 21 years.

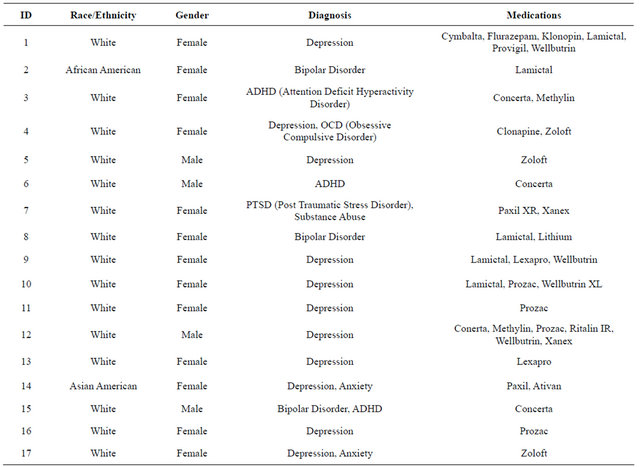

The study consisted of 76% females (n = 13) and 24% males (n = 4). In addition, the sample included 82% White college students (n = 14) and 18% other races (n = 3). Furthermore, 88% of the sample (n = 15) reported taking between one and three medications. See Table 1 for a summary of demographics by participant.

2.3. Instrument

The authors gathered data for the study using a modified semi-structured interview instrument, the Subjective Experience of Medication Interview [22]. The original instrument, AdultSEMI (Adult Subjective Experience of Medication Interview), has been utilized in previous studies [23,24] to collect narrative data from adults with schizophrenia about their experience taking psychiatric medication. However, this instrument was modified for undergraduate college students by asking developmen tally appropriate questions (pertaining to education, intimacy, university life, career).

The interview schedule, which is comprised of approximately 100 questions and takes approximately two hours to complete, includes eight categories related to illness, treatment, stigma, and medication: 1) treatment, illness, and medication history; 2) perceptions of medication; 3) managing, monitoring, and reporting of medication experience; 4) parent and student interaction regarding medication management; 5) illness and medication stigma; 6) medication management and university interactions; and 7) peer and intimate partner interactions and medication management. The authors constructed open-ended questions to elicit responses in conversational style and to minimize leading questions. For example, instead of asking “what is your diagnosis?” which would presuppose illness “understood as a diagnosis”, subjects were asked, “…you see Dr. X, would you describe in your own words what you see him/her for?”

Data were collected by social work and anthropology graduate students. Respondent answers to interview questions were recorded as audio files, transcribed, and

Table 1. Participant Demographics.

the resulting written narratives transferred to Atlas.ti [25], a software specifically designed for qualitative data coding and management.

2.4. Data Analytic Strategy

In the first analytic step, the authors open-coded participant responses to discover new or emergent themes. The significance of the themes was determined by “substantive significance” [26]. This significance refers to increasing depth of existing knowledge about the topic of study [27]. In open coding, respondent answers were coded by attaching code names to any of the students’ words that referenced perceptions of: 1) their need for treatment; 2) their need for psychiatric medications; 3) how others (i.e., parents, peers and teachers) perceive their need for medications; and 4) their utilization of disability services and mental health services. In the second step, researchers compared and contrasted coded quotations [28] and then grouped the codes by shared content. The authors compared and contrasted these latter codes and grouped them by themes that characterized their overall experience. It is important to note that the researchers’ data analytic strategy in this study remained open to positive and negative effects of psychiatric medication, even though much of their work has examined stigmatizing perceptions towards medication.

To establish a measure of coding reliability, the first author read and coded data from seven respondents and the third and fourth authors reviewed the codes, discussed differences and similarities, and as a team, established a master codebook. The master codebook was used to code the remaining 10 cases, and new codes were added when appropriate.

3. RESULTS

Four main themes emerged from the participant interviews regarding participants’ experience of taking psychiatric medication: higher functioning; mitigation of symptoms; willingness to disclose; and positive longterm outlook. The case examples that follow reflect these themes. Although the majority of participants endorsed having a positive experience with medication and had minimal trouble with stigma, one respondent had a different experience. This section concludes with a case example of a minority student whose experience with psychiatric medication and stigma differs from the majority of study participants.

Higher functioning

Participants reported that psychiatric medication allowed them to function at a higher level and enjoy a lifestyle similar to their peers:

It allows me to have a normal life and be on [the same] playing field as everyone else.

[Without medication] I wouldn’t be able to go to classes and hang out with my friends and do anything basically.

Mitigation of symptoms

Psychiatric medication appeared to mitigate negative symptoms that prevented some college students from focusing on academics and enjoying meaningful opportunities:

My social life is improving because I am able to go out. My schoolwork is improving because I’m able to focus on it. My family relationships are improveing because I am not freaking out all the time. …I feel like it (medication) improves everything.

I’m able to think in different ways. I’m able to get a lot more done, or I should say get things done period; but also I have a lot more courage and confidence, “cause I don’t …have all those nagging feelings of… ‘You’re worthless. Give up. No, I don’t want to do anything”…and I have initiative, and it’s a lot easier to interact socially when I don’t have all those [negative thoughts].

Willingness to disclose

The majority of these college students did not feel stigmatized by their use of psychiatric medication. They were open about their treatment to their peers and professors, when necessary, because of their success in addressing psychiatric symptoms and the important role medication plays:

I usually try to explain what happens to me if I don’t take medication, so that they can see cause and effect sort of.

Many students considered their psychiatric illness to be similar to other medical conditions, thus helping to normalize the experience of taking psychiatric medication:

Yeah, it’s really nothing different than…the pill I take for asthma…I just consider it something…for one of my sicknesses.

Finally, students were willing to disclose because they recognized the benefits to others if they shared their experience:

I tell people about my problems …It’s usually to break stigmas, because people have this impression of me as being this really strong, driven, determined person and when I tell them about…the stuff that I’ve experienced, it’s [to] …disprove them and say, “hey, I’m human too”.

It just kind of crosses their mind and then maybe that’s someone that they could be like, “Oh yeah… people can be bipolar and be normal,” and that doesn’t mean that you’re…crazy and you’re gonna shoot someone.

Positive long-term outlook

The positive effects of treatment influenced some participants’ outlook to prolong the use of psychiatric medication, especially as it enhances their college experience, and perhaps beyond. Although for some, this could indicate an inappropriate long-term reliance on the medication, most students felt medication would continue to be an essential tool in helping to manage psychiatric symptoms:

I don’t ever foresee myself ever even thinking…, “Oh hey, maybe I should go off of these,” because that just sounds like a horrible idea. I don’t even want to know what it it would be like without them now in my head.

It lets me enjoy being at college more.

Minority Perspective

The experience of the lone African American college student in the study varied from that of other students. This individual did report feeling stigma associated with her use of psychiatric medication. Furthermore, she had to navigate college with the burden of a “double stigma”: she was a racial minority in addition to having a severe mental illness. Her family had mistrust and stigmatizing perceptions toward psychiatric medication and this student’s parents were passing these beliefs to her. The following quotations, which are presented within two out of the three components of the framework of Corrigan & Watson’s (2002) [9] self-stigma model, (all three components do not have to be endorsed to experience selfstigma) illustrate the African American student’s experience of self-stigma.

One component of the adult self-stigma model [9] is “stereotype,” in which the individual applies the mental illness label and/or negative characteristic to the self. The student describes how she felt the first time she associated the concept of “mental illness” with herself:

I definitely felt like all of a sudden I just wasn’t normal, I wasn’t a normal person anymore, like some kind of freak. It was weird.

This student’s parents were intensifying the stress, negative feelings, and concerns the student had toward her need to take medication for the treatment of her mental illness:

My parents, they were really unhappy when I told them (about psychiatrist visit). They were like dead set against it. They said, “No you don’t have any problems…if you go, then it’s going to ruin your record. You won’t be able to get jobs.” …He [father] wants me to have as many opportunities as possible. So he thought that something like this could take away some of those opportunities.

Furthermore, this student felt a great deal of family resistance to adhere to the medication as prescribed by her psychiatrist:

Even after the first visit he (psychologist) was positive what it was [and] told me, “You’re going to have to go see a psychiatrist to prescribe you some medicine. I can’t do it”. He was really the only one that told me that, whereas well my parents were like, “No, you don’t need anything.” …But if there was any way, like if I was under 18, that they could’ve stopped me, they

Another component of the adult self-stigma model, “discriminate”, illustrates how the individual self-discriminates as he/she behaves in response to applying the mental illness label to self and agreeing with the negative stereotypes. In this example, the African American student avoids being seen in counseling services by her classmates who also receive services. She was ashamed to be identified as having a mental illness:

I’ve tried to…pull out all the measures I can to make sure no one knows anything. There was one time that I was at the university counseling center… I walked into the lounge and I saw someone there who was in my class, and I actually freaked out. I freaked out so much that I literally ran to the back, so I hope that…he didn’t see me or anything…that’s how desperate I am to make sure that no one knows anything about it. I always pick times when I know no one else is going to be around…

4. DISCUSSION

A common theme among students was how they attributed some of their college success to psychiatric medication, as it appeared to positively influence their ability to integrate in the university setting. This was exemplified by participants’ engagement in the same normative activities as other students, including: academic pursuits, school functions, and parties. They were academically thriving, which contributed to a perception that medication helped them to function on a higher level, focus and minimize mental health symptoms. In addition, students reported a willingness to disclose information to others regarding their psychiatric illness and use of medication. Students shared their experiences as a way to inform others about the importance of medication in keeping their symptoms at bay. In addition, they recognized the broader social benefit of their personal disclosure in helping to fight stereotypes regarding the behavior and functioning of those with mental illness.

Students reported minimal stigma. In part, this finding may be attributed to the positive effects of medication because it was perceived as improving everyday functioning. Ultimately, the fact that these students were successfully integrated within the college setting influenced peers and others in their environment to positively perceive them. Therefore, it is speculated that most participants did not experience typical consequences of stigma, such as a loss of opportunities and social exclusion.

The experience of the lone African American student raises important questions regarding the influence of familial perceptions on psychiatric treatment and community integration. Recent research [10] indicates that African American adolescents have a more intense experience of self-stigma in comparison with White adolescents. This was attributed to African American families expressing more negative views about mental illness stereotypes and characteristics to their children who have a psychiatric disability. The case example in this study also demonstrates how African American families may pass down negative beliefs about mental illness and mistrust to younger generations [12]. Indeed, a major factor contributing to the African American student’s selfstigmatization process was her parents’ lack of trust with the mental health system and negative stereotypes surrounding mental illness. The student internalized her parents’ negative stereotypes which, in turn, became detrimental to her own self-image. For instance, she described herself with the words “freak,” “crazy” and “weird”. These negative perceptions greatly impacted her level of shame and contributed to her decision to hide her need for medication and psychiatric services from others. Her parents engrained within her the idea that if she were identified as having a mental illness, she would lose out on meaningful opportunities. Although this student ultimately decided to accept treatment-and reported that doing so benefited her-she suffered from both familygenerated and internalized stigma more so than the majority of study participants.

More research is needed on college students’ attitudes and experiences surrounding the use of psychiatric medication. Additional research should be conducted at a variety of university and college settings including public and private institutions, community colleges, institutions with military or faith-based ties, and those in different geographic locations. Students of diverse races and cultures would be crucial groups to compare, especially since research [10,14] indicates minority groups’ reluctance to utilize psychiatric medications, and negative perceptions toward help-seeking for mental illness. In addition, minority students may experience multiple stigmas, which could increase the level of stigma they experience with regards to mental health concerns. Conducting research with students across a range of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds would help to sharpen awareness of the different cultural influences affecting students’ attitudes as well help to clarify the factors most likely to contribute to stigma or the propensity to self-stigmatize. Furthemore, it could be useful to compare and contrast the experiences of students who experienced the onset of mental health concerns after reaching adulthood with those who were diagnosed as children or adolescents. In addition to cross-sectional investigations, longitudinal studies would be rich sources of information on how students’ perceptions shift over time based on their experiences throughout college.

In order to help combat the stigma of mental health treatment in minority communities and allow for more equitable, culturally competent access, concerted education efforts need to be made by community mental health clinics, public agencies, leaders within the faith community, and college health services [29]. Educational campaigns that resonate with people of different ethnic groups and feature “champions” from within the community could help to normalize the process of seeking help. In addition, primary care doctors as well as mental health professionals need to receive training on culturally sensitive ways to assess their patients for mental health conditions and to engage them in treatment. When minority families feel more at ease seeking assistance for mental health concerns, their children may emerge into adulthood with fewer negative perceptions of seeking psychiatric help. Obtaining a college education can be a challenging endeavor even in the absence of mental illness. Helping students from diverse backgrounds feel more comfortable accessing needed mental health services would help to support not only the psychological health of students but also their chances at meeting their educational, professional, and social goals.

Limitations

Although the findings described in this study provide useful preliminary information on how some college students taking psychiatric medication characterize the experience, we cannot generalize the results of this study to a larger population due to the qualitative nature of the study. The findings described here represent a small cohort of self-selected students who were mostly White and attending a competitive, private, Midwestern university. Furthermore, findings pertaining to the achievement of developmental milestones were difficult to extract because the data was cross-sectional. Therefore, it is not possible to determine if the students in this study were able to successfully navigate the tasks of early adulthood similarly to other college students. Despite these limitations, the study provides encouraging evidence that some college students are positively benefitting from psychiatric medication with minimal stigma.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Presidential Research Initiative grant program from Case Western Reserve University.

REFERENCES

- Kadison, R. and Digeronimo, T. (2004) College of the overwhelmed. Jossey Bass, San Francisco.

- Blanco, C., Okuda, M., Wright, C., Hasin, D., Grant, B., Liu, S., et al. (2008) Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: Results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 1429-1437. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429

- Leavey, J. (2005) Youth experiences of living with mental health problems: Emergence, loss, adaptation and recovery. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 24, 109-126.

- Kroger, J. (2007) Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E. and Hunt, J. (2009) Mental health and academic success in college. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9. doi:10.2202/1935-1682.2191

- Goffman, E. (1963) Stigma: Notes of the management of spoiled identity. Prentice Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs.

- Karp, D. (2006) Is it me or my meds? Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Link, B. and Phelan, J. (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363-385. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Corrigan, P. and Watson, A. (2002) The paradox of selfstigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 9, 35-53. doi:10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35

- Kranke, D., Floersch, J., Kranke, B. and Munson, M.R. (2011) A qualitative investigation of self-stigma among adolescents taking psychiatric medication. Psychiatric Services, 62, 893-899. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.62.8.893

- Herrick, C. and Brown, H. (1998) Underutilization of mental health services by Asian-Americans residing in the United States. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 19, 225- 240. doi:10.1080/016128498249042

- Mathews, A., Corrigan, P., Smith, B. and Aranda, F. (2006) A qualitative exploration of African Americans’ attitudes toward mental illness and mental illness treatment seeking. Rehabilitation Education, 20, 253-268. doi:10.1891/088970106805065331

- Romero, A. and Roberts, R. (2003) The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 2288-2305. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01885.x

- Williams, D., Costa, M. and Leavell, J. (2010) Race and mental health: Patterns and challenges. In: Scheid, T. and Brown, T., Eds., A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories and Systems, Cambridge University Press, New York, 268-290.

- Dixon, C. and Vaz, K. (2005) Perceptions of African Americans regarding mental health counseling. In: Harley, D. and Dillard, J., Eds., Contemporary Mental Health Issues among African Americans, American Counseling Association, Alexandria, 163-174.

- Kranke, D. and Bartholomew, J. (2010) Minority college student mental health: Gaps and future directions. Council of Social Work Education, Portland.

- Rusch, N., Lieb, K., Bohus, M. and Corrigan, P. (2006) Brief reports: Self-stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57, 399. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.399

- Zimmerman, M. and Warschausky, S. (1998) Empowerment theory for rehabilitation research: Conceptual and methodological issues. Rehabilitation Psychology, 43, 3- 16. doi:10.1037/0090-5550.43.1.3

- Linhorst, D. (2006) Empowering people with severe mental illness. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Corrigan, P., Mueser, K., Bond, G., Drake, R. and Solomon, P. (2008) Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation. The Guilford Press, New York.

- Golberstein, E., Eisenberg, D. and Gollust, S.E. (2009) Perceived stigma and helpseeking behavior: Longitudinal evidence from the healthy minds study. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1254-1256. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1254

- Floersch, J., Townsend, L., Longhofer, J., Munson, M., Winbush, V., Kranke, D., et al. (2009) Adolescent experience of psychotropic treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry, 46, 157-179. doi:10.1177/1363461509102292

- Jenkins, J. (1997) Subjective experience of persistent psychiatric disorder: Schizophrenia and depression among US Latinos and Euro-Americans. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 20-25. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.1.20

- Jenkins, J., Strauss, M., Carpenter, E., Miller, D., Floersch, J. and Sajatovic, M. (2005) Subjective experience of recovery from schizophrenia-related disorders and typical antipsychotics. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 51, 211-227. doi:10.1177/0020764005056986

- Muhr, T. (1993) Atlas.ti Software Development, Berlin.

- Patton, M. (2002) Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Floersch, J., Longhofer, J., Kranke, D. and Townsend, L. (2010) Integrating thematic, grounded theory and narrative analysis: A case study of adolescent psychotropic treatment. Qualitative Social Work Journal, 9, 407-425. doi:10.1177/1473325010362330

- Boeije, H. (2002) A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality & Quantity, 36, 391-409. doi:10.1023/A:1020909529486

- Kranke, D., Guada, J., Kranke, B. and Floersch, J. (2012) What do African American youth with a mental illness think about help-seeking and psychiatric medication? Origins of stigmatizing attitudes. Social Work in Mental Health, 10, 53-71. doi:10.1080/15332985.2011.618076