American Journal of Plant Sciences

Vol.4 No.6(2013), Article ID:32909,5 pages DOI:10.4236/ajps.2013.46152

Comparative Efficacy of Different Herbicides for Weed Management and Yield Attributes in Wheat

![]()

1Crop Physiology and Production Center (CPPC), National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement, MOA Key Laboratory of Crop Physiology, Ecology and Cultivation (The Middle Reaches of Yangtze River), Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China; 2Department of Plant Science, Faculty of Biological Science, Quaid-I, Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan; 3Department of Horticultural, Northeast Agricultural University (NEAU), Harbin, China.

Email: *jhuang@mail.hzau.edu.cn

Copyright © 2013 Shah Fahad et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received April 9th, 2013; revised May 10th, 2013; accepted June 1st, 2013

Keywords: Weeds; Herbicides; Wheat

ABSTRACT

Weed competes with crops for water, nutrients and light so weed infestation is one of the major threats to crop. Present investigation was aimed to asses the comparative efficacy of different herbicides for weed management in wheat crop under agro-climatic conditions of Pakistan. This experiment was laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) design with five replications. Different herbicides were used for weed management in wheat crop. The post emergence application of herbicides included Aim 40 DF @ 0.02 kg a.i. ha–1, Agritop 500 GL–1 @ 0.43 kg a.i. ha–1, Isoproturon 50 WP @ 1 kg a.i. ha–1, Puma super 75 EW @ 0.75 kg, Topik 15 WP @ 0.04 kg and Buctril super 60 EC @ 0.45 kg. For comparison hand weeding and weedy check were also included. In each replication six treatments of these six herbicides were kept. The significantly affected parameters were fresh weed biomass (kg·ha–1), thousand grain weight (g), number of tillers m–2, weed control efficiency (%) and grain yield (kg·ha–1). Statistical analysis showed that maximum weed efficiency (84%) was recorded for Isoproturon 50 WP whereas minimum value (37%) was for Aim 40 DF. Similarly maximum number of tillers m–2 (250) was recorded for Isoproturon 50 WP and minimum (133) in weedy check. The herbicide Isoproturon 50 WP @ 1.0 kg a.i. ha–1 was applied at post emergence performed well and exhibited effectively weed control and better yield in wheat.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is an important cereal grain crop all over the world. It is the staple food crop of Pakistan. It contributes 13.1 percent to the value added in agriculture and 2.8 percent to GDP. During 2008-2009, it was grown on an area of 9.062 million ha–1 with an annual production of 19.5 million tons of grains giving average yield of 23.421 tons ha–1 [1] which is far below the yield level obtained in other wheat growing countries of the world. Every effort is being made to meet the wheat requirements of the country. There are many reasons for low yield of wheat crop but weed infestation is the basic and major component of low yield in crop production system. With the advent of new short stature varieties, weeds competition has become even more severe.

The estimated annual losses caused by weeds may be more than 10 billions rupees in Pakistan [2]. Because of high competitive ability and high reproductive potential of weeds, it is imperative to check their infestation. Only due to high weed infestation, average yield losses in wheat crop are about 25% - 30% in Pakistan [3]. Weeds compete with crops mainly for light, nutrients, water and CO2 for canopy development and other growth requirements [4]. Weeds utilize three to four times more nitrogen, potassium and magnesium than a weed free crop [5]. [6] reported that yield losses due to weed are in proximity of 17 - 25 percent which in terms of wheat grain comes to about 2.43 to 3.57 million tons annually.

The weed control has been practiced since the time immemorial by manual labour and/or animal drawn implements, but these practices were laborious, tiresome and expensive due to increasing cost of labour. Weed management increases the cost of production and thus it is necessary to device such methods which could reduce not only the cost of production but also save time and labor. Among the weed control methods, the chemical control is the easiest one of the recent origins, and the most successful alternative method. Chemical weed control enables farmers to obtain higher yields per unit area with an over all lower production cost. The chemical method of weed control can provide us abrupt and promising results. Herbicides are a quick tool to control dense weed populations. Moreover, the control is more effecttive as the weeds even within the rows are killed which invariably escape, because of morphological similarity to wheat, during mechanical control. Selective herbicides reduce the need for hand weeding. The effectiveness of herbicides is affected by time, rate and method of application.

Out of total import of herbicides worth Rs. 2.2 billion, 63% were used on wheat alone during 2004 in Pakistan. Herbicides are frequently used to increase crop yield through effective weed control, but excessive and nonjudicious use of herbicides has posed many environmental and health problems [7]. According to an international survey, over 295 biotypes of 177 weed species have evolved resistance to herbicides [8]. These environment and health hazards and resistance development issues, therefore, have forced to develop some environment friendly technologies for weed control [7].

Chemical weed control is more economical than conventional method [9,10]. Reports are available on the efficacy of different herbicides in wheat [11-14]. Puma Super 75 EW and Topik 15 WP are most commonly used narrow-leaved herbicides in the region but there are several reservations on the use of these herbicides as high application often involves the heavy expenditures and causes environmental hazard in addition to adverse affects on wheat crop. Similarly, low application could result the problem of low or no control of weeds and weed resistance etc. The herbicide use in Pakistan is not widely practiced as in the agriculturally advanced nations. The interest around the testing of graminicides [15,16] indicates the problem posed by grasses whereas, the studies of Khan [12] showed synergistic response on combined use. In another studies researchers obtained an effective control of weeds in wheat through chemicals [17].

The objectives of the present studies were to determine the efficacy of different most effective and economical herbicides as compared to hand weeding in controlling weeds and to detect their effect on the yield and yield components of wheat crop under conditions of Pakistan.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted at Agricultural Extension Farm, Dargai, KPK during 2008-2009. The experiment was laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) design with five replications. Seeds of wheat plant were obtained from National Agricultural Research Council (NARC). Seeds were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol followed by gentle shaking in 10% chlorox solution for 2 - 3 min and subsequently washed with distilled water and then cultivated in field in November of 2008 and 2009. The soil analysis showed that experimental field is Clay loam in texture with pH of 6.4, organic matter 1.05%, 19.12 ppm phosphorus, 115 ppm Potash, 36.72 ppm NO3– 27.71 ppm Fe, 1.25 ppm Zn and 3.56 ppm Cu . NPK were applied to field at rate of 100-75-50 Kg·ha–1.

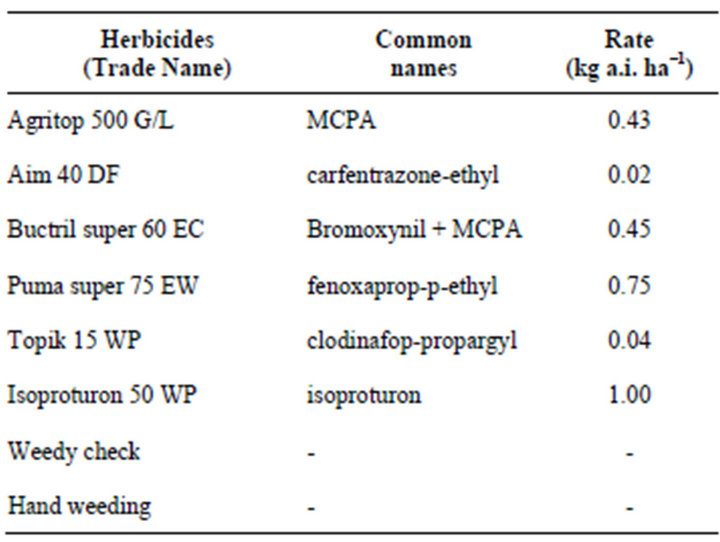

Throughout the growing season recommended irrigation practices were carried out. Six treatments were made in each replication with a size of 5 × 1.8 m2. Row to row distance was kept at 25 cm apart. All the herbicides were applied as post emergence as presented in Table 1. All the herbicides were applied with the help of a knapsack sprayer 20 days after sowing when the wheat crop was in the 5 - 6 leaf stage. Different herbicides rates were determined in terms of active ingredient or acid equivalent per acre treated, or as pounds or volume of commercial product per acre. Active ingredient indicates the amount of non-acid herbicide in a formulation. Acid equivalent indicates the amount of an acid herbicide in a formulation. Different weeds present at the time of herbicides application were Convolvulus arvensis, Avena fatua, Phalaris minor, Gallium aparine, Fumaria indica and Melilotus indica, etc.

To avoid any misuse of the herbicides all the precautionary measures were taken to spray them successfully. The data were recorded on the parameters fresh weed biomass (kg·ha–1), weed control efficiency (%), number of tillers·m–2, thousand grain weight (g), biological yield (kg·ha–1) and grain yield (kg·ha–1).

Table 1. Different herbicides used for weed management in wheat crop in Pakistan.

Statistical Analysis

Data were taken for year 2008-2009 and after that combine mean was calculated for both years. The data of all the parameters were then individually subjected to ANOVA technique by using the MSTATC computer software. Fisher’s Protected LSD test [18] was used for the separation of means.

3. Results

The data recorded on weed control efficiency (%), fresh weed biomass (kg·ha–1), thousand grain weight (g), number of tillers m–2 and grain yield (kg·ha–1) were significantly affected by the different herbicides treatments, whereas biological yield (kg·ha–1) was found non-significant. The results for the studied traits are presented as under:

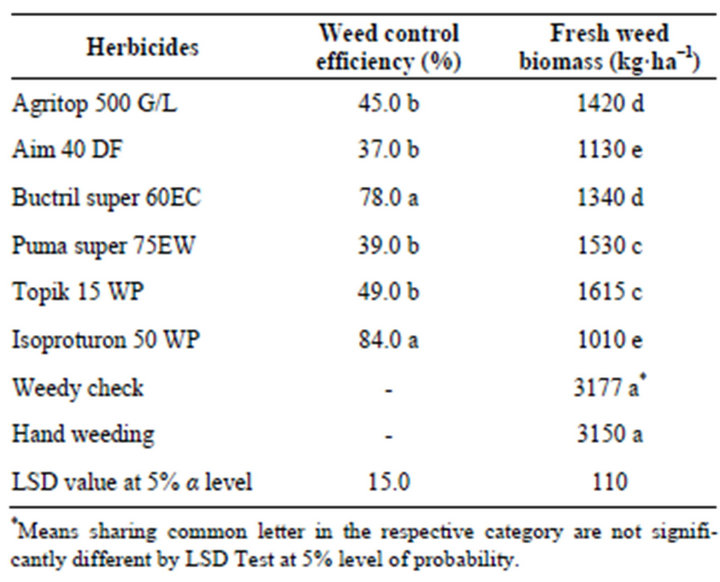

3.1. Weed Control Efficiency (%)

Data analysis showed that different herbicides significantly affected the weed control efficiency. The data of weed control efficiency presented in Table 2. The maximum weed efficiency (84 %) was recorded for Isoproturon 50 WP while the minimum value (37%) was recorded for Aim 40 DF.

3.2. Fresh Weed Biomass (kg·ha–1)

Fresh weed biomass was significantly affected by different herbicides application. Data of fresh weed biomass (Table 2) showed that maximum fresh weed biomass (3177 kg·ha–1) was reported in the plot of weedy check while minimum weed biomass (1010 kg·ha–1) was reported in the Isoproturon 50 WP followed by Aim 40 DF (1130 kg·ha–1).

Table 2. Comparative weed control efficiency (%) and fresh weed biomass (kg·ha–1) as affected by different herbicides in wheat crop in Pakistan.

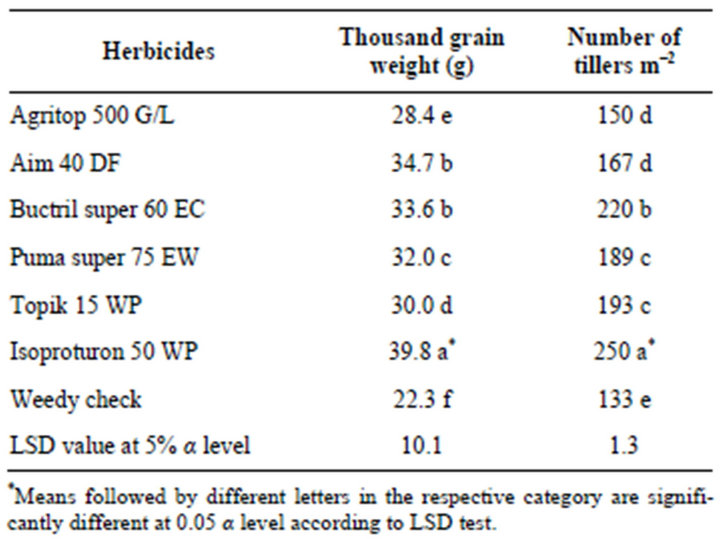

3.3. Thousand Grain Weight (g)

The statistical data showed significant effect on thousand grain weight (Table 3). Thousand grain weight was maximum (39.8 g) in plots treated with Isoproturon 50 WP followed by Aim 40 DF (34.7 g) whereas minimum value (22.3 g) was recorded from weedy check.

3.4. Number of Tillers m–2

Different herbicides significantly affected the number of tillers m–2 (Table 3). Statistical analysis showed that maximum number of tillers m–2 (250) was recorded for Isoproturon 50 WP while the minimum number of tillers m–2 (133) was observed in weedy check.

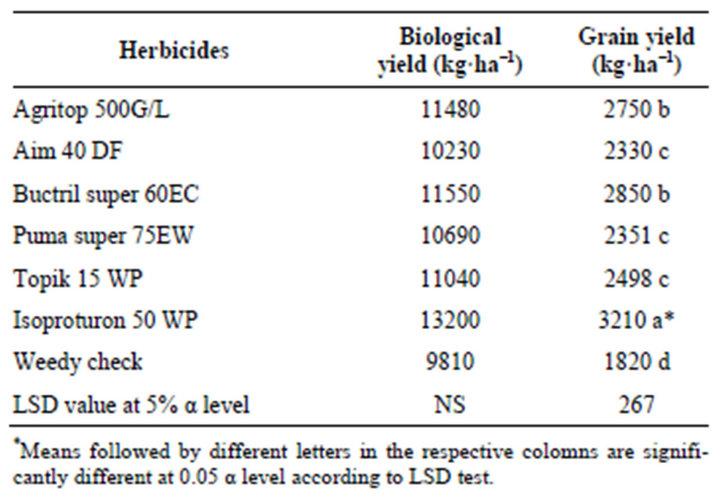

3.5. Biological Yield (kg·ha–1)

Analysis of variance exhibited that herbicides did not affect the biological yield. The effects of different herbicides are presented in Table 4. The data revealed that

Table 3. Thousand grain weight (g) and Number of tillers m–2 as affected by different herbicides in wheat crop in Pakistan.

Table 4. Biological yield (kg·ha–1) and grain yield (kg·ha–1) as affected by different herbicide treatments in wheat crop in Pakistan.

maximum biological yield of (13,200 kg·ha–1) was reported for Isoproturon 50 WP and minimum value (9810 kg/ ha) was reported for weedy check.

3.6. Grain Yield (kg·ha–1)

All herbicides for weed management significantly affect grain yield. Table 4 demonstrated the effect of different herbicides on grain yield. The maximum value of grain yields of 3210 kg·ha–1 was observed in Isoproturon 50 WP treated plots followed by Buctril super 60 EC (2850 kg·ha–1). Minimum value of grain yields of 1820 kg·ha–1 was observed in weedy check plots.

4. Discussion

The prosperity of our people depends to a large extent on good wheat harvests. Weeds are a major problem and reduce the yield of wheat. Weeds reduce the crop yield, deteriorate the quality of farm produce and hence reduce the market value of wheat. The control of weeds is basic requirement and major component of management in the production system [19]. The chemical control method is one of the recent origins, which is being emphasized in modern agriculture [20]. [21] reported that identification of narrow-leaved weeds impedes in manual control due to which herbicide application is necessary. Furthermore, if the chemical control is tested in areas where wheat is intercropped with sugarcane, it may provide fruitful results [22].

Weeds control by chemical method, aiming balance shifting of the agro-ecosystem in favor of cultivated crop, which proved to be relatively more efficient and economical. The efficacy of herbicides, however, depends more upon their formulation in addition to time, methods and rates of application [23]. It was concluded from an experiment that hand weeding and mixture of herbicides Puma super 75 EW and Buctril-M 40 EC showed better results for controlling winter weeds [24].

[25] while evaluating 5 post-emergence herbicides alone at recommended doses and in combination with DMA-6 for weed control in wheat concluded that herbicide application suppressed weed population effectively. Dosanex + DMA-6 and Arelon provided the best weed control. However, Dicuran M.A. 60 WP + DMA-6 produced the maximum grain yield. DMA-6 alone and in combination with Dicuran M.A. 60 WP was more economical than all other herbicidal treatments. [26] investtigated the effect of different graminicides used at varying levels and concluded that lesser dose of Topik15WP is required for the control of wild oat as compared to Puma Super 75 EW.

The maximum weed efficiency (84%) was noted for Isoproturon 50 WP while minimum value (37%) was observed for Aim 40 DF (Table 2). These results are in line with [13] who reported that herbicides application effectively controlled weeds. These findings are also in conformity with those of [27], who reported that herbicides significantly reduced weed density. Similarly, [28] stated that Puma Super 75 EW @ 1.25 L·ha–1 gave maximum control of narrow-leaved weeds in wheat out of varying herbicides applied at different doses.

The best performance of Isoproturon 50 WP and other herbicidal applications could be attributed to the best control of weeds due to minimal weed competition which caused an increased flow of nutrients towards the grain and ultimately yield was increased. These results are supported by [11,12,29]. They reported that herbicidal treatments significantly increased the grain yield in wheat.

The maximum number of tillers m–2 (250) was noted for Isoproturon 50 WP whereas minimum number (133) was reported in weedy check. These results showed that maximum weed control enhanced the production of fertile tillers m–2 which subsequently contributed towards the increase in wheat yield. These results are in agreement with the work of [30] who obtained an increase in tillering with the application of different herbicides.

The low yield (1820 kg·ha–1) in weedy check plots indicated that weeds utilize maximum resources of the main crop which ultimately reduced the crop yield. These results are in conformation with those of [31], who applied Puma Super 75 EW and Topik 15 WP at different doses to control Avena fatua in wheat crop and reported that lesser dose of Topik 15 WP and higher dose of Puma Super 75 EW was required to control this weed.

5. Acknowledgements

We thank the funding provided by the Key Technology Program R&D of China (Project No. 2012BAD04B12) and MOA Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (No. 201103003).

REFERENCES

- Anonymous, “Area, Production and yield of wheat in Agricultural Statistics of Pakistan,” Economic Adviser’s Wing Islamabad, 2009.

- S. Ahmad, “Weed Problem in Pakistan,” Presidential Address of 25th Science Conference, Bahawalpur, 1992.

- M. Nayyar, M. Shafi and T. Mahmood, “Weed Eradication Studies in Wheat, Abstract,” 4th Pakistan Weed Science Conference, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, 26-27 March 1994.

- W. P. Anderson, “Weed Science Principles,” 2nd Edition, West Publishing Company, St. Paul, 1983, pp. 33-42.

- P. J. Schwezel and P. E. l. Thomas, “Weed Competition in Cotton,” PANS, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1971, pp. 30-34.

- R. A. Shad, “Status of Weed Science Activities in Pakistan,” Progressive Farming, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1987, pp. 10- 16.

- K. Jabran, Z. A. Cheema, M. Farooq, S. M. A. Basra, M. Hussain and H. Rehman, “Tank Mixing of Allelopathic Crop Water Extracts with Pendimethalin Helps in the Management of Weeds in Canola (Brassica napus) Field,” International Journal of Agriculture and Biology, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2008, pp. 293-296.

- I. Heap, “The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds,” Online, Internet, 2 March 2005.

- M. S. Cheema, M. A. Iqbal and M. S. Ahmad, “Economics of Weed Control in Wheat,” Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1988, pp. 32-36.

- M. S. Cheema, M. Afzal, M. S. Ahmad and M. Aslam, “Efficiency of Different Methods of Weed Control in Wheat,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1988, pp. 24-33.

- M. A. Khan, M. Zahoor, I. Ahmad, G. Hassan and M. S. Baloch, “Efficacy of Different Herbicides for Controlling Broadleaf Weeds in Wheat (Triticum aestivum),” Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1999, pp. 732-734. doi:10.3923/pjbs.1999.732.734

- I. Khan, Z. Muhammad, G. Hassan and K. B. Marwat, “Efficacy of Different Herbicides for Controlling Weeds in Wheat Crop-1. Response of Agronomic and Morphological Traits in Wheat Variety GHAZNAVI-98,” Scientific Khyber, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2001, pp. 51-57.

- I. Khan, G. Hassan and K. B. Marwat, “Efficacy of Different Herbicides for Controlling Weeds in Wheat Crop-II. Weed Dynamics and Herbicides,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 8, No. 1-2, 2002, pp. 41-48.

- M. A. Qureshi, A. D. Jarwar, S. D. Tunio and H. I. Majeedano, “Efficacy of Various Weed Management Practices in Wheat,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 8, No. 1-2, 2002, pp. 63-69.

- U. S. Walia, L. S. Brar and B. K. Dhaliwal, “Performance of Clodinafop and Fenaxapro-p-Ethyl for the Control of Phalaris minor in Wheat,” Indian Journal of Weed Science, Vol. 30, No. 1-2, 1998, pp. 48-50.

- N. J. Ormeno and S. J. Diaz, “I Coldinafop, a New Herbicide for the Selective Control of Grassy Weeds in Wheat. II Selectivity on Spring and Alternative Cultivars,” Agricultura Técnica, Vol. 58, No. 2, 1998, pp. 103-115.

- M. H. Khan, G. Hassan, N. Khan and M. A. Khan, “Efficacy of Different Herbicides for Controlling Broadleaf Weeds in Wheat,” Asian Journal of Plant Sciences, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2003, pp. 254-256. doi:10.3923/ajps.2003.254.256

- R. G. D. Steel and J. H. Torrie, “Principles and Procedures of Statistics a Biological Approach,” 2nd Edition, McGraw Hill Book Co., Inc. New York, 1980.

- F. L. Young Jr., A. G. Ogg, D. L. Young and R. I. Papendick, “Weed Management for Crop Production in the Northwest Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Region,” Weed Science, Vol. 44, No. 2, 1996, pp. 429-436.

- F. H. Taj, A. Khattak and T. Jan, “Chemical Weed Control in Wheat,” Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1986, pp. 15-21.

- S. S. Seefeldt, J. E. Jensen and E. P. Fuerst, “Log Logistic Analysis of Herbicides Dose Response Relationships,” Weed Technology, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1995, pp. 218-227.

- K. B. Marwat, Z. Hussain, B. Gul and M. Saeed, “Chemical Weed Management in Wheat Intercropped with Sugarcane,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2005, pp. 145-150.

- A. Majid, M. R. Hussain and M. A. Akhtar, “Studies on Chemical Weed Control in Wheat,” Journal of Agricultural Research, Vol. 21, No. 4, 1983, pp. 167-171.

- A. Khan, M. Ilyas and T. Hussain, “Response of Wheat to Herbicides Application and Hand Weeding under Irrigated and Non-Irrigated Conditions,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 11, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 1-9.

- S. Ahmad, Z. A. Cheema, R. M. Iqbal and F. M. Kundi, “Comparative Study of Different Weedicides for the Control of Broadleaved Weeds in Wheat,” Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1991, pp. 1-9.

- G. Hassan, H. Khan, M. Latif, M. I. Khan and S. A. Khan, “Tolerance of Avena fatua and Phalaris minor to Some Graminicides,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 11, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 69-73.

- I. Shahid, “Screening of Different Herbicides for Controlling Weeds in Wheat Crop,” M.Sc. Hons. Thesis, Faculty of Agriculture, Gomal University, Dera Ismail Khan, 1994.

- S. C. Muhammad, M. Akhter and M. Iqbal, “Performance of Different Herbicides in Wheat under Irrigated Conditions of Southern Punjab,” Weed Science Society of Pakistan Abstract, 2006, p. 21.

- M. I. Marwat, H. K. Ahmad, K. B. Marwat and G. Hassan, “Integrated Weed Management in Wheat-II. Tillers m–2, Productive Tillers m–2, Spikelets spike–1, Grains spike–1, 1000 grain Weight and Grain Yield,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 9, No. 1-2, 2003, pp. 23-31.

- G. Hassan, B. Faiz, K. B. Marwat and M. Khan, “Effects of Planting Methods and Tank Mixed Herbicides on Controlling Grassy and Braodleaf Weeds and Their Effect on Wheat CV. Fakhre-Sarhad,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 9, No. 1-2, 2003, pp. 1-11.

- G. Hassan, H. Khan and M. G. Rabbani, “Quantification of Tolerance of Different Wild Oat Biotypes to Clodinafop-Proparrgyl and Fenoxoprop-p-Ethyl,” Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Vol. 11, No. 3-4, 2005, pp. 151-155.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.