Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:29120,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojvm.2013.31011

Comparison of Antibody Detection with Yeast Lysate Antigens Prepared from Blastomyces dermatitidis Dog Isolates from Wisconsin and Tennessee

Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, USA

Email: *robejes2@isu.edu

Received December 21, 2012; revised January 22, 2013; accepted February 23, 2013

Keywords: Blastomyces dermatitidis; Blastomycosis; ELISA; Lysate Antigen; Antibody Detection

ABSTRACT

Blastomyces dermatitidis, the causative agent of blastomycosis, a potentially lethal dimorphic fungal disease of humans and animals has been difficult to diagnose in the clinical laboratory. We are attempting to develop and improve immunodiagnostic assays by producing novel yeast lysate reagents for the detection of antibodies in blastomycosis. The objective of this study was to use lysate antigens prepared from four B. dermatitidis antigens isolated from dogs infected with blastomycosis from two different endemic areas (Wisconsin and Tennessee) testing for the detection of antibodies in serum specimens from immunized rabbits and infected dogs using the indirect ELISA. In the dog sera, absorbance values ranged from 0.774 to 1.350, while the rabbit sera values ranged from 0.533 to 1.191. Antigen T-58 appeared to lack any geographical specificity in antibody detection, which could prove useful in future immunodiagnostic detection of blastomycosis infections.

1. Introduction

Blastomycosis is a systemic and potentially fatal fungal disease of humans and animals caused by the thermally dimorphic organism Blastomyces dermatitidis. The infection results following inhalation of spores produced by the filamentous (mycelial) phase of the organism present in soil or associated with vegetation [1]. The spores convert into large yeast cells due to the increase in temperature in the lungs. The infection may exist as a primary acute or chronic manifestation in the pulmonary tissue, which resembles tuberculosis, or it may spread from the lungs to other sites including internal organs, bone, skin and possibly to the central nervous system in which meningitis may result [2-5]. The prognosis is poor if dissemination occurs before a diagnosis of the disease is established [6-8]. Blastomycosis and other systemic fungal diseases are now considered “emerging fungal threats” since they may infect individuals with normal immune systems, but, more importantly, they can produce extensive disease and possibly death in patients with diseases that compromise the immune system [9].

In recent years researchers and physicians have stimulated considerable interest with their attempts to develop improved methods to combat the dramatic increase in the systemic fungal diseases [5,6]. Ongoing research activities have been centered around developing novel ways of diagnosing, preventing, and treating these potentially devastating infections. Lately the thrust of our research has been associated with investigations on ways in which we may learn more about the immunobiology of blastomycosis and to develop improved methods for diagnosis.

With regard to diagnosis of the disease various methods have been employed, including culturing and histopathology, but in many instances these procedures are time-consuming or may fail to yield the desired results. The use of immunological assays in the clinical laboratory generally provide for a more rapid diagnosis, but most of the previous tests for the detection of antibodies have been of limited value due to problems with sensitivity and specificity [4,6,9].

As a result, more investigators in the field of medical mycology have been involved in attempts to develop reliable immunodiagnostic procedures for blastomycosis and other systemic fungal diseases [10-22]. Our laboratory has been involved in the development of antigenic reagents from various isolates of B. dermatitidis [22] and the evaluation of these novel yeast phase lysate antigens for the detection of antibodies or antigens in those infected with blastomycosis. Encouraging results have been evidenced with some of these reagents when assays were performed using various adaptations of the enzyme immunoassay [23-30]. These studies have contributed greatly to our knowledge concerning potential avenues of approach with regard to future investigations.

In preliminary studies with lysate antigens prepared from B. dermatitidis isolates from different United States geographical regions, evidence seemed to indicate that antigens prepared from northern and southern strains varied in their ability to detect antibodies depending on the source of the serum specimen. Therefore the objective of this present study was to perform a comparative evaluation using lysate antigens prepared from Wisconsin and Tennessee dog isolates for ELISA antibody detection in serum specimens from both northern and southern regions of the United States.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Lysate Antigens

Mycelial phase cultures of four different B. dermatitidis isolates (WI-R and WI-J Wisconsin dog isolates; T-66 and T-58 Tennessee dog isolates) were converted to yeast cells by culturing at 37˚C on brain heart infusion agar. Yeast phase lysate reagents were prepared by a method similar to one that was previously used for the production of antigen from Histoplasma capsulatum [31-33] and modified in our laboratory for B. dermatitidis lysate antigen production [22]. The yeast phase cells were grown for 7 days at 37˚C in a chemically defined medium in an incubator shaker, harvested by centrifugation (700 × g; 5 minutes), followed by washing with distilled water, resuspended in distilled water and then allowed to lyse for 7 days at 37˚C in water with shaking. The preparations were centrifuged, filter sterilized, merthiolate added (1:10,000) and stored at 4˚C for further use. Protein determinations were performed on the lysates using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL) and dilutions of the antigenic reagents used in the assays were based on protein concentration.

2.2. Serum Specimens

A number of serum specimens from dogs with blastomycosis from both northern and southern regions of the US were provided by Dr. A.M. Legendre (University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine, Knoxville, TN). In addition, sera from rabbits immunized with various yeast lysate antigens prepared from B. dermatitidis isolates from these same geographical regions were also assayed to determine and compare the efficacy of the lysates as immunodiagnostic reagents.

2.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The ability of each yeast lysate reagent to detect antibodies in the above serum specimens was determined using the indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Each lysate antigen was diluted (2000 ng/ml of protein) in a carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) and then added to triplicate wells (100 µl) of a Costar 96-well microplate (Fisher-Thermo). The plates were then incubated overnight at 4˚C in a humid chamber followed by washing three times with phosphate buffered saline containing 0.15% Tween 20 (PBS-T). The serum specimens (1:2500 dilution; 100 µl) were added to the microplate wells and incubated for 30 minutes at 37˚C in a humid chamber. Following this incubation the wells were washed as above and 100 µl of goat anti-species (either dog or rabbit) IgG (H & L) peroxidase conjugate (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, MD) was added to each well and incubated for 30 minutes at 37˚C. The plates were again washed as above and 100 µl of peroxidase substrate (Pierce/Fisher-Thermo) will be added to each well and incubated for approximately 2 minutes at room temperature. The reaction will be stopped by the addition of sulfuric acid and the absorbance read at 450 nm using a BIO-RAD 2550 EIA reader.

3. Results

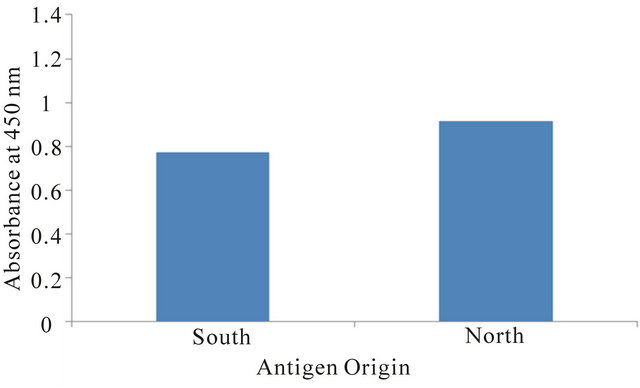

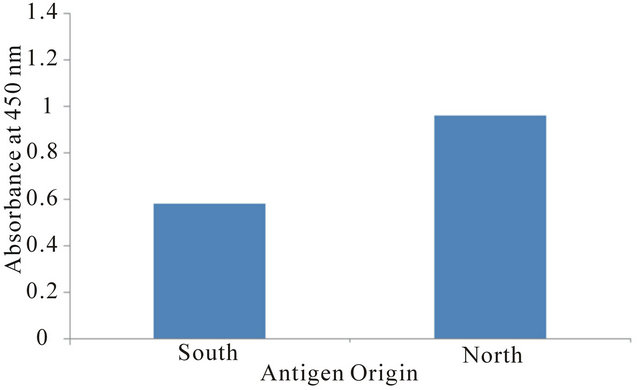

As shown in Figure 1, 28 dog serum samples were collected from dogs infected with B. dermatitidis from the south (Tennessee) and north (Wisconsin) regions. The Wisconsin (WI-R) antigen efficacy was tested using the standard ELISA assay against antibody from the south and north. Absorbance values were compared looking for a high antibody-antigen affinity. The average absorbance values were 0.774 and 0.914 from the south and north respectively.

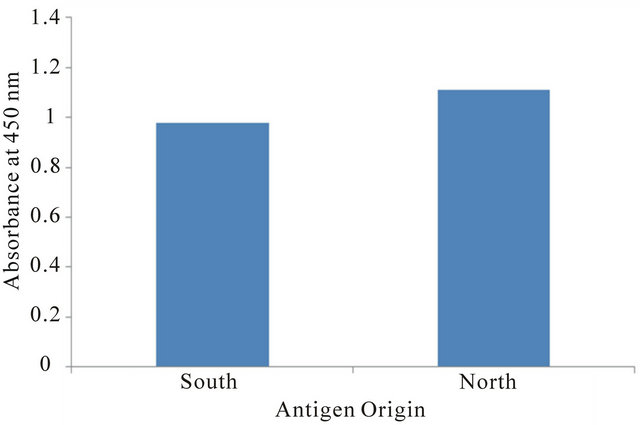

Figure 2 represents 28 dog serum specimens collected from dogs infected with B. dermatitidis from Wisconsin and Tennessee. The Wisconsin (WI-J) antigen efficacy was tested using the standard ELISA assay. The average absorbance values were 0.978 and 1.112 from the south and north respectively.

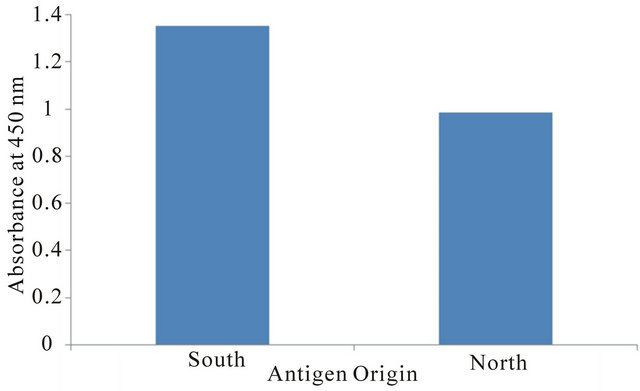

Twenty-eight dog serum samples were collected from dogs infected with B. dermatitidis from Wisconsin and Tennessee areas (see Figure 3). The standard ELISA assay was used to testthe Tennessee (T-66) antigen efficacy against antibody from the south and north. The average absorbance values were 1.350 and 0.986 from the south and north respectively.

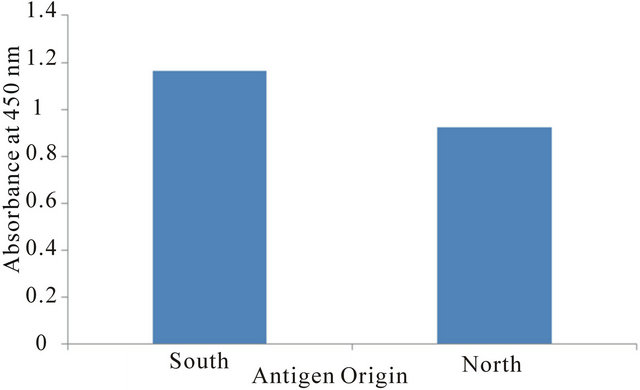

As shown in Figure 4, dog serum specimens were collected from 28 dogs infected with B. dermatitidis from the north and south regions. The Tennessee (T-58) antigen efficacy was tested and absorbance values were compared looking for a high antibody-antigen affinity. The average absorbance values were 1.163 and 0.922 from the south and north respectively.

Figure 5 shows results from 28 rabbit serum speci-

Figure 1. The mean absorbance value of 28 dog serum specimens were assayed against the WI-R antigen.

Figure 2. The mean absorbance value of 28 dog serum specimens assayed using the WI-J antigen.

Figure 3. The mean absorbance value of 28 dog serum specimens were assayed against the T-66 antigen.

Figure 4. The mean absorbance value of 28 dog serum specimens were assayed using the T-58 antigen.

mens immunized with WI-R B. dermatitidis antigen. The Wisconsin (WI-R) antigen efficacy was tested using the standard ELISA assay against antibody from the south (Tennessee) and north (Wisconsin). Absorbance values were compared looking for a high antibody-antigen affinity. The average absorbance values were 0.580 and 0.960 from the south and north respectively.

Twenty-eight rabbit serum specimens were collected from rabbits infected with WI-J B. dermatitidis antigen. The Wisconsin (WI-J) antigen reactivity was tested against antibody from Tennessee and Wisconsin. The average absorbance values were 0.533 and 0.872 from the south and north respectively (see Figure 6).

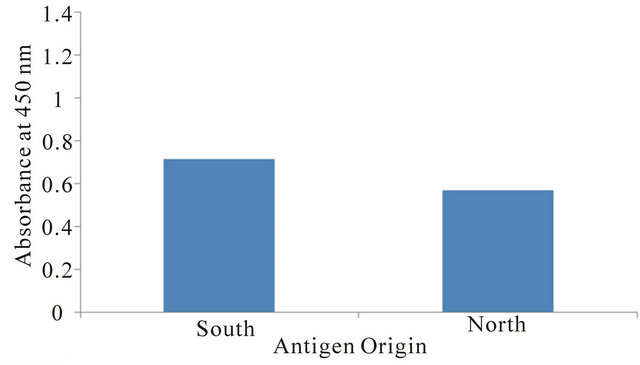

As seen in Figure 7, 28 rabbit serum samples were collected from T-66 B. dermatitidis immunized rabbits. The Tennessee (T-66) antigen efficacy was tested using the standard ELISA assay against antibody from the south and north. The average absorbance values were 0.717 and 0.567 from the south and north respectively.

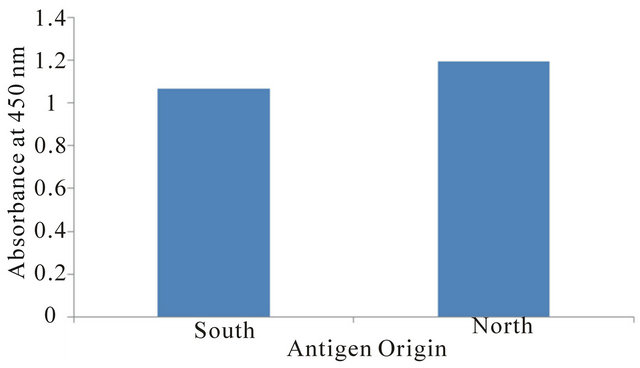

Serum samples from 28 rabbits immunized with T-58 B. dermatitidis antigen. The Tennessee (T-58) antigen efficacy was tested using the standard ELISA assay. Absorbance values were compared looking for a high antibody-antigen affinity. The average absorbance values were 1.067 and 1.191 from the south and north respectively (see Figure 8).

Figure 5. The mean absorbance value of 28 rabbits serum specimens were assayed using the WI-R antigen.

Figure 6. The mean absorbance value of 28 rabbit serum specimens were assayed using the WI-J antigen.

Figure 7. The mean absorbance value of 28 rabbit serum specimens were assayed using the T-66 antigen.

Figure 8. The mean absorbance value of 28 rabbit serum specimens were assayed using the T-58 antigen.

4. Discussion

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a fungal organism found primarily in the southeastern and south-central states that border the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and is highly endemic in the Wisconsin and Tennessee areas. Four antigens, two from the north (WI-R and WI-J) and two from the south (T-66 and T-58), were used to test for the antibody present in serum samples collected from infected dogs and immunized rabbits. It seems that there may be some correlation between an antigen’s geographical origin and its ability to detect antibodies from the same region. As seen in Figures 1-7, antigens from the north detected antibodies in the northern samples more strongly, and antigens from the south detected antibodies in the southern samples with greater efficacy. However, Figure 8, which examined antigen T-58 in rabbit sera, did not follow this trend, with the southern antigen detecting the antibodies present in the northern serum specimens more strongly.

Despite the observed correlation, the variation between location for each antigen doesn’t appear to be substantial. Therefore, it is likely that of the tested antigens, any can be used to detect the presence of antibodies in serum samples regardless of those samples’ geographical origin. Specifically, antigen T-58 appeared to universally detect antibodies regardless of geographical origin. This lack of region specificity in future antibody detection would be useful in immunodiagnostic techniques. Additionally, studies are in progress to determine if combinations of the above antigens could provide an even greater diagnostic response.

Antibodies were detected more strongly in dog sera when compared to rabbit sera. In the dog sera, absorbance values ranged from 0.774 to 1.350, while the rabbit sera values ranged from 0.533 to 1.191. This may be related to dogs being infected with B. dermatitidis rather than being immunized, as the rabbits were. In addition, might the amount of antibodies be due to the length of time infected with B. dermatitidis? The rabbit serum samples were collected a maximum of three weeks after immunization with B. dermatitidis, whereas the dogs were infected for an unknown length of time. Perhaps this could lead to further investigation.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Daniel Jackson and Pratik Katwal for their help in data collection.

This research was supported by the Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID 83209-8007.

REFERENCES

- A. F. DiSalvo, “Blastomycosis, in Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections,” 9th Edition, Arnold Publishers, London, 1998, pp. 337-355.

- R. W. Bradsher, “Clinical Features of Blastomycosis,” Seminars in Respiratory Infections, Vol. 12, No. 3, 1997, pp. 229-234.

- R. W. Bradsher, S. W. Chapman and P. G. Pappas, “Blastomycosis,” Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2003, pp. 21-40. doi:10.1016/S0891-5520(02)00038-7

- J. R. Bariola and K. S. Vyas, “Pulmonary Blastomycosis,” Seminars in Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 32, No. 6, 2011, pp. 745-753. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1295722

- J. A. McKinnell and P. G. Pappas, “Blastomycosis: New Insights into Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment,” Clinical Chest Medicine, Vol. 30, No. , 2009, pp. 227-239. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2009.02.003

- M. Saccente and G. L. Woods, “Clinical and Laboratory Update on Blastomycosis,” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2010, pp. 367-381. doi:10.1128/CMR.00056-09

- J. A. Smith and C. A. Kauffman, “Pulmonary Fungal Infections,” Respirology, Vol. 17, No. 6, 2012, pp. 913-926.

- J. A. Smith and C. A. Kauffman, “Blastomycosis,” Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2010, pp. 173-180. doi:10.1513/pats.200906-040AL

- J. E. Cutler, G. S. Deepe Jr. and B. S. Klein, “Advances in Combating Fungal Diseases: Vaccines on the Threshold,” Nature Review of Microbiology, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2007, pp. 13-18. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1537

- R. W. Bradsher, “Detection of Specific Antibodies in Human Blastomycosis by Enzyme Immunoassay,” Southern Medical Journal, Vol. 88, No. 12, 1995, pp. 1256-1259. doi:10.1097/00007611-199512000-00013

- C. A. Hage, T. E. Davis, L. Egan, M. Parker, D. Fuller, A. M. LeMonte, D. Durkin, P. Connelly, L. J. Wheat, D. Blue-Hindy and K. A. Knox, “Diagnosis of Pulmonary Histoplasmosis and Blastomycosis by Detection of Antigen in Bronchoalveolar Lavage fluid Using an Improved Second-Generation Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay,” Respiratory Medicine, Vol. 101, No. 1, 2007, pp. 43-47. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2006.04.017

- B. S. Klein and J. M. Jones, “Isolation, Purification, and Radiolabeling of a Novel Surface Protein on Blastomyces dermatitidis Yeasts to Detect Antibody in Infected Patients,” Journal of Clinical Investigation, Vol. 85, No. 1, 1990, pp. 152-161. doi:10.1172/JCI114406

- K. S. Vyas, J. R. Bariola and R. W. Bradsher, “Advances in the Serodiagnosis of Blastomycosis,” Current Fungal Infection Reports, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2008, pp. 227-231. doi:10.1007/s12281-008-0033-z

- B. S. Klein, R. A. Squires, J. K. Lloyd, D. R. Ruge and A. M. Legendre, “Canine Antibody Response to Blastomyces dermatitidis WI-1 Antigen,” American Journal of Veterinary Research, Vol. 61, No. 5, 2000, pp. 554-558. doi:10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.554

- D. Spector, A. M. Legendre, J. Wheat, D. Bemis, B. Rohrbach, J. Taboada and M. Durkin, “Antigen and Antibody Testing for the Diagnosis of Blastomycosis in Dogs,” Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2008, pp. 839-843. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0107.x

- J. F. Shurley, A. M. Legendre and G. M. Scalarone, “Blastomyes dermatitidis Antigen Detectioni in Urine Specimens from Dogs with Blastomycosis Using a Competitive Binding Inhibition ELISA,” Mycopathologia, Vol. 160, No. 2, 2005, pp. 137-142. doi:10.1007/s11046-005-3153-9

- M. Durkin, L. Estok, D. Hospenthal, N. Crum-Cianflone, S. Swartzentruber, E. Hackett and L. J. Wheat, “Detection of Coccidioides Antigenemia Following Disssociation of Immune Complexes,” Clinical Vaccine Immunology, Vol. 16, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1453-1456. doi:10.1128/CVI.00227-09

- J. R. Bariola, C. A. Hage, M. Durkin, E. Bensadoun, P. O. Gubbins, L. J. Wheat and R. W. Bradsher, “Detection of Blastomyces dermatitidis Antigen in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Blastomycosis,” Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Vol. 69, No. 2, 2011, pp. 187-191. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.015

- P. Connolly, C. A. Hage, J. R. Bariola, E. Bensadoun, M. Rodgers, R. W. Bradsher and J. J. Wheat, “Blastomyces dermatitidis Antigen Detection by Quantitative Enzyme Immunoassay,” Clinical Vaccine Immunology, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2012, pp. 53-56. doi:10.1128/CVI.05248-11

- D. R. Allton, R. G. Rivard, P. A. Connolly, S. McCall, M. M. Durkin, T. M. Boyd, J. P. Flanagan, L. J. Wheat and D. R. Hospenthal, “Detection of Latin American Strains of Histoplasma in a Murine Model by Use of a Commercially Available Antigen Test,” Clinical Vaccine Immunology, Vol. 17, No. 5, 2010, pp. 802-806.

- C. A. Hage, J. A. Ribes, N. L. Wengenack, L. M. Baddour, M. Assi, D. S. McKinsey, K. Hammoud, D. Alapat, N. E. Babady, M. Parker, D. Fuller, A. Noor, T. E. Davis, M. Rodgers, P. A. Connolly, B. El Haddab and L. J. Wheat, “A Multicenter Evaluation of Tests for Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 53, No. 5, 2011, pp. 448-454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- S. M. Johnson and G. M. Scalarone, “Preparation and ELISA Evaluation of Blastomyces dermatitidis Yeast Phase Lysate Antigens,” Diagostic Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1989, pp. 81-86. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(88)90076-4

- J. L. Bono, A. M. Legendre and G. M. Scalarone, “Detection of Antibodies and Delayed Hypersensitivity with Rotofor Preparative IEF fractions of Blastomyces dermatitidis Yeast Phase Lysate Antigens,” Journal of Medical and Veterinary Mycology, Vol. 33, No. 4, 1995, pp. 209- 214. doi:10.1080/02681219580000441

- M. A. Fisher, J. L. Bono, R. O. Abuodeh, A. M. Legendre and G. M. Scalarone, “Sensitivity and Specificity of an Isoelectric Focusing Fraction of Blastomyces dermatitidis Yeast Lysate Antigen for the Detection of Canine Blastomycosis,” Mycoses, Vol. 38, No. 5-6, 1995, pp. 177- 182. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1995.tb00046.x

- R. C. Axtell and G. M. Scalarone, “Serological Differences in Three Blastomyces dermatitidis Strains,” Mycoses, Vol. 45, No. 11-12, 2002, pp. 437-442.

- C. M. Sestero and G. M. Scalarone, “Detection of IgG and IgM in Sera from Canines with Blastomycosis Using Eight Blastomyces dermatitidis Yeast Phase Lysate Antigens,” Mycopathologia, Vol. 162, No. 1, 2006, pp. 33-37. doi:10.1007/s11046-006-0028-7

- C. M. Sestero and G. M. Scalarone, “Detection of the Surface Antigens BAD-1 and Alpha (1-3) Glucan in Six Different Strains of Blastomyces dermatitidis Using Monoclonal Antibodies,” Journal of Medical and Biological Science, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2006, pp. 1-7.

- J. F. Shurley and G. M. Scalarone, “Isoelectric Focusing and ELISA Evaluation of a Blastomyces dermatitidis Human Isolate,” Mycopathologia, Vol. 164, No. 2, 2007, pp. 73-76. doi:10.1007/s11046-007-9033-8

- W. O. Hatch and G. M. Scalarone, “Comparison of Colorimetric and Chemiluminescent ELISAs for the Detection of Antibodies to Blastomyces dermatitidis,” Journal of Medical and Biological Sciences, Vol. 3, No 1, 2009, pp. 1-6.

- J. C. Wright, T. E. Harrild and G. M. Scalarone, “The Use of Isoelectric Focusing Fractions of Blastomyces dermatitidis for Antibody Detection in Serum Specimens from Rabbits Immunized with Yeast Lysate Antigens,” Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2012, pp. 237-241. doi:10.4236/ojvm.2012.24038

- H. B. Levine, G. M. Scalarone and S. D. Chaparas, “Preparation of Fungal Antigens and Vaccines: Studies on Coccidioides immitis and Histoplasma capsulatum,” Contributions to Microbiology and Immunology, Vol. 3, 1977, pp. 106-125.

- G. M. Scalarone, H. B. Levine and S. D. Chaparas, “Delayed Hypersensitivity Responses of Experimental Animals to Histoplasmin from the Yeast and Mycelial Phases of Histoplasma capsulatum,” Infection and Immunity, Vol. 21, No. 3, 1978, pp. 705-713.

- H. B. Levine, G. M. Scalarone, G. D. Campbell, R. C. Graybill and S. D. Chaparas, “Histoplasmin-CYL, A Yeast Phase Reagent in Skin Test Studies in Humans,” American Review of Respiratory Diseases, Vol. 119, No. 4, 1979, pp. 629-636.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.