Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.05 No.05(2015), Article ID:56519,7 pages

10.4236/ojn.2015.55053

Factors Influencing Practice of Patient Education among Nurses at the University College Hospital, Ibadan

Modupe Olusola Oyetunde, Atinuke Janet Akinmeye

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Email: modupeoyetunde@gmail.com, akinmodesola@gmail.com

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 18 April 2015; accepted 19 May 2015; published 22 May 2015

ABSTRACT

Patient education is the process of influencing patient behaviour and producing the changes in knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to maintain or improve health. Health education may be general preventive, health promotion or diseases specific education. With an education system in place, patients will be satisfied with care, patients will be healthier, and will seek medical services less frequently. There is little or no documentation on the practice of patient education at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. The aim of this descriptive study was to explore factors influencing the practice of patient education among nurses at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. Stratified and simple random sampling techniques were used in selecting 200 nurses at the University College Hospital Ibadan. A self-designed questionnaire was used to collect data. Statistical package for social sciences version 15 (SPSS 15) was used in analysing data. The study revealed that the knowledge and practice of patient education among the nurses in University College Hospital was high and the knowledge was found to be significantly associated with its practice (X2 = 7.89, p = 0.017). The working experience of nurses does not determine whether they practice patient education or not. Almost all the respondents (70% - 90%) in this study affirmed that the nurses’ experiences, cultural barriers, work place culture, lack of time, heavy workload, insuffi- cient staffing, and the complexity of patients’ condition were important factors that influenced the practice of patient education. In conclusion, nurses at the University College Hospital have good knowledge and positive attitude towards patient education but could not practice effectively. A more critical approach in addressing heavy workload, insufficient staffing, among others is needed to improve patient education. Further studies should be carried out on developing nurses’ roles as patient educators.

Keywords:

Patient Education, Patient Education Process, Outcome of Care

1. Introduction

Given the changing disease panorama, increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, and escalating health care cost, patient education becomes more important on the agenda now as ever. The need for nurses to teach others and to help others learn will continue to increase in the healthcare environment [1] . Patient education has long been considered a major component of standard care given by nurses [2] . Education is the key to having compliant patients. It has been proven that education system improves patients’ satisfaction with care, health status, and reduction in request for medical services [3] . Throughout the history of nursing, nurses have helped patients take responsibility for their own health [4] . Florence Nightingale attested to teaching as a function of nursing in her treatises on nursing in 1859 [5] . The quality of nursing care can be measured in part, by the quality of patient and family education provided [6] .

Many studies revealed that nurses regarded patient education as a significant part of everyday practice [7] [8] and as a specific responsibility [9] . Nurses who perceived higher levels of responsibility in their teaching roles also performed teaching activities more frequently [10] .

Several studies also revealed that patient education was not considered part of routine care, but rather as conditional to other work demands [11] [12] . In parallel, the educator role was described as difficult to grasp [12] . Even if nurses expressed enthusiasm for their patient-education role, it was not the same as knowing how to teach [13] [14] . In several studies, knowledge of teaching and learning was considered to be important, and a need for more education, training and skills to undertake patient teaching was emphasized [15] [16] . Although some studies [17] [18] show that nurses feel competent in their teaching role, others point to lack of training and lack of confidence as contributing factors in nurses’ reluctance to conduct patient education [15] [16] . Another aspect of competence is the significance of having factual knowledge, which means knowing what to teach [16] . In a study of nurses and physicians [19] , 85% of the participants had good knowledge of treating illness, while 68% had good knowledge of its impact on everyday life. The content of the information nurses gave in counselling sessions was dependent on their length of nursing experience (49%), ward routines (29%) and professional training (19%) [19] . A nurse’s positive attitude to patient education improved with length of service [20] .

Lack of time was reported as an obvious hindrance to patient education [21] . Adequate time was regarded as important in creating a trustful relation as was adequate documentation [21] . Patient and family teaching was ranked as the fifth most time-consuming activity of the eight responsibilities that staff nurses were asked to rank [22] . A study revealed that nurses working in outpatient units had more time for patient education than those working in a ward [15] . Good-quality patient education requires appropriate resources of time, facilities and equipment. The significance of allocating a place for teaching and being left alone without interruptions was described as important [16] .

Supportive administration is needed for the accomplishment of patient education [16] . In a study, 69% of the nurses agreed that supervisors or managers emphasized the importance of patient teaching [23] . While another study shows that heavy workload is a barrier to the accomplishment of patient education [24] . Other aspects were insufficient staffing, lack of organizational support in completing nursing duties to allow time for teaching [25] , nurses taking care of a larger number of patients than recommended, which affected the time given to each patient, and the complexity of the patients’ disease or health situation [26] . The use of teaching materials is of importance for successful patient education [26] . Lack of materials, supplies or teaching tools to adequately teach the patient was reported as frustrating [25] . It is important that the work place culture values education and this requires organizational support to develop empowerment and to facilitate nurses’ fulfilment of their educational roles. Organizational development is needed to create high quality patient education.

Anecdotal experience shows that patients appear not to have information about their disease process, nursing and medical management. This observation was made from the various questions posed by patients for enlightenment and clarifications. These are questions that would not have been raised if the patients had been duly educated. Patient education promotes patients’ compliance, patients’ satisfaction with care, healthy lifestyles and maximizes patients’ self-care skills among other effects; although these all seem to be grossly deficient in patients. In an age where patients pay more health care, demand for quality care is on the increase. Efforts to reduce patients’ stay and payment among others become a nursing concern. Exploring the factors influencing the practice of patient education is an attempt to solve this problem. It is against this background that the researchers seek answers to the following questions.

1) Are nurses knowledgeable about the practice of patient education?

2) Do nurses practice patient education?

3) What factors could influence the practice of patient education?

4) Is there any perceived effect of patient education on outcome of care?

2. Method

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional survey designed to collect information about factors influencing the practice of patient education among nurses at University College Hospital (UCH).

2.1. Research Setting

Study setting is the University College Hospital Ibadan with the principal focus on nurses working in the hospital. This is the first teaching hospital in Nigeria established in 1957. The hospital was established solely to provide health care services for the masses and to train various health professionals. The vision for its establishment includes being a stimulus for medical education in West Africa, centre of excellence and scientific research in nursing and medical sciences. It is national reference centre for all forms of health problems and an institution for higher learning second to none in Black Africa. The tertiary institution has about 1004 nurses.

2.2. Target Population

The target population comprises of all registered nurses of University College Hospital, Ibadan. There are about 1004 nurses working in the University College Hospital, Ibadan.

2.3. Sampling Technique

The study population comprises of nurses working in both inpatient and outpatient departments of University College Hospital, Ibadan. The study population was selected using stratified and then simple random sampling technique. The accessible population from the selected strata of units was 507. The units selected were; Medicine, Surgery, Obstetrics & Gynecology and out-patient departments.

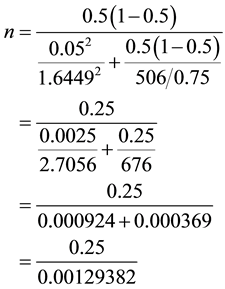

2.4. Sample Size Determination

The sample size was obtained using;

Formula

where

n = sample size;

N = Accessible population;

p = estimated variance in population as a decimal (0.5);

A = precision desired expressed in decimal (0.05);

Z = based on confidence level 1.6449 for 90%;

R = estimated response rate expressed in decimal (0.75 for 75%).

Given N = 570

n = 193

Consideration for attrition; 10% attrition rate,

10% attrition rate = 19.3

n = 193 + 19

n = 212

A proportionate sample of each stratum was used in the course of distributing the questionnaires.

2.5. The Research Instrument

The study utilized a 52 item structured and self-administered questionnaire. The instrument was divided into two major sections A and B. Section A: dealt with Socio-demographic data of the respondents. Section B addressed the research questions. i) Knowledge and practice of patient education; ii) Factors influencing practice of patient education; iii) Relationship between patient education and outcome of care; iv) Perception of ways of improving patient education among nurses.

The instrument was developed after a thorough review of literature. The face and content validity was ensured by subjecting the instrument to critical review among colleagues. Suggested corrections were effected. A test retest at two weeks interval was carried out among 20 nurses with similar characteristics to ensure reliability and consistency of the instrument. The data were analyzed and a Chronbach’s alpha score of 0.75 was obtained.

Procedure for data collection: Due ethical considerations were given and observed. Institutional and individual permission were obtained prior administration of questionnaire. Trained research assistant were employed to distribute and collect questionnaires. At the point of data collection, consent was sought again verbally and 1 out of 3 nurses who consented was given questionnaire in the selected units. The research assistants made use of the various shifts moving from one nurse to the other and from one ward to another. The data collection lasted for three weeks, retrieval rate was 100 per cent but only 90% (200) was valid for analysis.

2.6. Procedure for Data Analysis

The complete questionnaires were coded and subjected to statistical analysis using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15 (SPSS 15). The hypotheses were tested using Chi square test and the level of significance was set at alpha 5%.

3. Results

Socio Demographic Variables

This was done by analysing the first seven items on the questionnaire. In all a total of 200 nurses participated in the study. The mean age of respondents was 34.0 ± 8.6 years, with about 80% of them being 40 years or less. Fourteen (7.0%) were males while 186 (93.0%) were females. More than 80% of the respondents were Yoruba. The educational qualification of these nurses is quite high; 46 (24.0%) were registered nurses, 90 (46.9%) were registered nurses or midwives, 34 (17.7%) had bachelor’s degree in nursing, while others have postgraduate degrees such as masters and PhD. The professional cadre of these nurses ranges from Assistant Director of Nursing (ADN) to nursing officer (NO II). Half of the nurses who participated in this study had been working for eight years or less; also one hundred (50.0%) work at the medical ward, 40 (20.0%) at surgical wards, 40 (20.0%) at O & G, and 20 (10.0%) at out-patients department (Table 1).

The knowledge and practice of patient education among the nurses sampled for this study is high. More than 90% stated that they actually practiced patient education and believed that patient education should be included in their plan of care, nurses are responsible for providing reliable discharge information, that patients should be informed about their health care options, and that it is necessary to document after patient teaching. About 80% of our respondents stated that patient education should be individualized, that patient teaching should be done after identifying their needs, and that they assess their patients for learning needs.

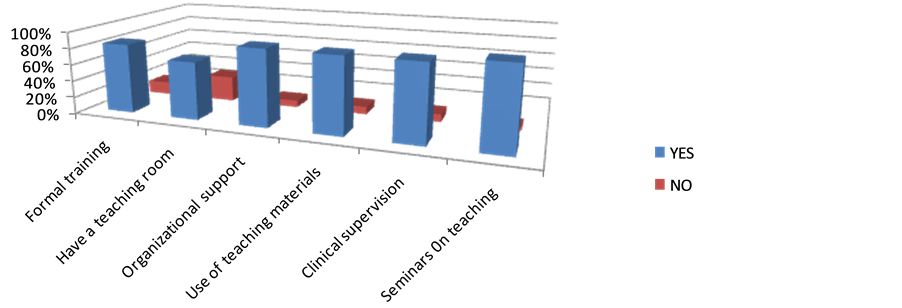

Figure 1 shows the factors that determine the practice of patient education among UCH nurses. A large proportion of these respondents agreed that those nurses’ experiences, cultural barriers, work place culture, lack of time, heavy workload, insufficient staffing, and the complexity of patients’ condition are factors that influence the practice of patient education.

Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure 3 were used to report findings of each research question.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

*RN: registered nurse; **RN/RM: RN and registered midwife; ***BNSc: bachelor of nursing science.

Table 2. Knowledge and practice of patient education among the respondents.

Figure 1. Factors that determine practice of patient education.

Figure 2. Perceived effects of patient education on outcome of care.

Figure 3. Suggested ways of improving practice of patient education.

4. Discussion of Findings

The term “patient education” in this study refers to formal and informal interactive activities performed by health care professionals, aiming at achieving better health outcomes for patients. This is achieved through the provision of information, knowledge and skills that are necessary for the management of their health and illness concerns. Despite the fact that nurses are often regarded as the best health care professionals for effective patient education, their capacity to do this has been frequently questioned [3] [14] .

This study reveals that knowledge of patient education was found to be significantly associated with its practice (X2 = 7.89, p = 0.017). This is contradictory to the results that nurses’ knowledge and skills were largely inadequate but their attitudes to patient-education were positive [12] .

In this study it was found that the year of working experience of nurses whether high or low will not determine whether they practice patient education or not. This contradicts the opinion that a nurse’s positive attitude to patient education improved with length of service and that the content of the information nurses gave in counselling sessions was dependent on their length of nursing experience (49%), ward routines (29%) and professional training (19%) [15] . Nevertheless, experienced nurses and those with advanced degrees were more comfortable teaching patients about diagnosis and treatments.

Similar factors stated in other studies that influences the practice of patient education include insufficient staffing, lack of organizational support in completing nursing duties to allow time for teaching, nurses taking care of a larger number of patients than recommended, which affected the time given to each patient, and the complexity of the patients’ disease or health situation [16] , poor coordination of education, inadequate time, and work place culture, and lack of forums for discussion and clinical supervision of educational activities [12] and organizational development [23] .

In this study, nurses affirmed that the use teaching materials are of utmost importance for successful patient teaching. 82% of their respondents evaluated their command of written counselling as good, but computer-aided counselling and audiocassettes were used very little [15] . Lack of materials, supplies or teaching tools to adequately teach the patient was reported as frustrating [6] .

The nurses also stated that the involvement of other medical disciplines will improve patient education. The significance of interdisciplinary cooperation is emphasized in several studies but obstacles are also described [8] .

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the study revealed that nurse’ experiences, cultural barriers, work place culture, lack of time, heavy workload, insufficient staffing, and the complexity of patients’ condition were the factors influencing the practice of patient education. Findings from this study revealed that, the knowledge of patient education determined the practice of patient education; the working experience did not determine practice of patient education; the educational qualifications of nurses influenced the practice of patient education among nurses in the University College Hospital, Ibadan.

References

- Avsar, G. and Kasikci, M. (2011) Evaluation of Patient Education Provided by Clinical Nurses in Turkey. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 17, 67-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01908.x

- Balcou-Debussche, M. and Debussche, X. (2008) Type 2 Diabetes Patient Education in Reunion Island: Perceptions and Needs of Professionals in Advance of the Initiation of Primary Care Management Network. Diabetes and Metabolism, 34, 375-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2008.03.002

- Bird, A. and Wallis, M. (2002) Nursing Knowledge and Assessment Skills in the Management of Patients Receiving Analgesia via Epidural Infusion. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40, 522-531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02409.x

- Carpenter, J.A. and Bell, S.K. (2002) What Do Nurses Know about Teaching Patients? Journal of Nursing Development, 18, 157-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00124645-200205000-00009

- Deccache, A. and Aujoulat, I. (2001) A European Perspective: Common Developments, Differences and Challenges in Patient Education. Patient Education and Counseling, 44, 7-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00096-9

- Fitzpatrick, A. and Hyde, A. (2005) What Characterizes the “Usual” Preoperative Education in Clinical Contexts? Nursing and Health Sciences, 7, 251-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2005.00244.x

- Friedman, A.J., Cosby, R., Boyko, S., Hatton-Bauer, J. and Turnbull, G. (2011) Effective Teaching Strategies and Methods of Delivery for Patient Education: A Systematic Review and Practice Guideline Recommendations. Journal of Cancer Education, 26, 12-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13187-010-0183-x

- Gregor, F.M. (2001) Nurses’ Informal Teaching Practices: Their Nature and Impact on the Production of Patient Care. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38, 461-470. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00081-X

- Hubley, J. (2006) Patient Education in the Developing World―A Discipline Comes of Age. Patient Education and Counseling, 61, 161-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.011

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (2001) Hospital Accreditation Standards, Oakbrook Terrace.

- Jones, R.A. (2010) Patient Education in Rural Community Hospitals: Registered Nurses’ Attitudes and Degrees of Comfort. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 41, 41-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20091222-07

- Kääriäinen, M. and Kyngäs, H. (2010) The Quality of Education Evaluated by the Health Personnel. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 24, 548-556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00747.x

- Kendall, S., Deacon-Crouch, M. and Raymond, K. (2007) Nurses’ Attitudes toward Their Role in Patient Discharge Medication Education and Toward Collaboration with Hospital Pharmacists: A Staff Development Issue. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 23, 173-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NND.0000281416.04731.3e

- Latter, S., Rycroft-Malone, J., Yerrell, P. and Shaw, D. (2000) Evaluating Educational Preparation for a Health Education Role in Practice: The Case of Medical Education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 1282-1290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01599.x

- Lipponen, K., Kyngäs, H. and Kääriäinen, M. (2006) Surgical Nurses Readiness for Patient Counselling. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing, 10, 221-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joon.2006.10.013

- Marcum, J., Ridenour, M., Shaff, G., Hammons, M. and Taylor, M. (2002) A Study of Professional Nurses’ Perceptions of Patient Education. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 33, 112-118.

- Moret, L., Rochedreux, A., Chevalier, S., Lombrail, P. and Gasquet, I. (2008) Medical Information Delivered to Patients: Discrepancies Concerning Roles as Perceived by Physicians and Nurses Set Against Patient Satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling, 70, 94-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.011

- Park, M.Y. (2005) Nurses’ Perception of Performance and Responsibility of Patient Education. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 35, 1514-1521.

- Park, M.Y. and McMillan, M.A. (2000) Patient Education in the Face of Work Constraints. Paper Presented at the 1st Asia-Pacific Nursing Congress, Seoul.

- Sally, H., Karen, D. and Fran, L. (2005) Patient Education in Health and Illness. 5th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- Sigurdardottir, A.K. (1999) Nurse Specialists’ Perceptions of Their Role and Function in Relation to Starting an Adult Diabetic on Insulin. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 8, 512-518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00279.x

- Thoma, G.B. (1999) A Comparison of the Role of Patient Educator to Other Nursing Roles: Identifying Influences Affecting the Attainment of the Patient Educator Role among Staff Nurses. Microform University of Memphis, Memphis.

- Zakrisson, A.B. and Hägglund, D. (2010) The Asthma/COPD Nurses’ Experience of Educating Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Primary Health Care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 24, 147-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00698.x

- Turner, D., Wellard, S. and Bethune, E. (1999) Registered Nurses’ Perceptions of Teaching: Constraints to the Teaching Moment. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 5, 14-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172x.1999.00147.x

- Halse, K.M., Fonn, M. and Christiansen, B. (2014) Health Education and the Pedagogical Role of the Nurse: Nursing Students Learning in the Clinical Setting. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 4, 30-38.

- Abdi, A., Izadi, A., Vafaeei, K. and Lorestani, E. (2014) Assessment of Patient Education Barriers in Viewpoint of Nurses and General Physicians. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 8, 2252-2256. www.irjabs.com