Open Journal of Preventive Medicine

Vol.4 No.5(2014), Article ID:46228,11 pages DOI:10.4236/ojpm.2014.45040

A Qualitative Exploration of South African Women’s Psychological and Emotional Experiences of Infertility

Athena Pedro, Michelle Andipatin

Psychology Department, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

Email: aspedro@uwc.ac.za

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 27 February 2014; revised 6 May 2014; accepted 19 May 2014

ABSTRACT

Despite the high prevalence of infertility in Africa, the study of reproductive health in Africa, has for the most part, not addressed the impact of involuntary childlessness on women. In contrast, the health priority has been on fertility regulation rather than on infertility. In Sub-Saharan Africa, at least 20% - 50% of couples of reproductive age experience a fertility problem and 30% are diagnosed with infertility. This study explored a sample of South Africa women’s psychological and emotional experiences of infertility or involuntary childlessness. Utilising a qualitative methodology, 21 married women who were diagnosed with infertility were recruited. Semi-structured, indepth individual interviews were conducted and the data were analysed using thematic analysis. The results of the study indicated that the women reported emotional turmoil characterised by emotions such as disappointment and shock, anger and frustration, a deep sense of sadness and then progressed to experience a sense of acknowledgement that a problem existed. Within each of these emotional phases the emotions of hope and optimism were present. The findings of this study suggest that severe psychological and emotional tug-of-war effects accompany infertility. Possible coping strategies for women struggling with infertility are discussed.

Keywords:Infertility, Psychological and Emotional Trauma, Motherhood, Involuntary Childlessness

1. Introduction

Despite the high prevalence of infertility in Africa, and the evidence showing infertility to be a major reproductive health problem with immense social consequences, the study of reproductive health in Africa, has for the most part, not addressed the impact of involuntary childlessness on women [1] -[4] . In contrast, the health priority has been on fertility regulation rather than on infertility [1] -[4] . Population control, as a priority, has often negated the impact of involuntary childlessness [5] -[7] .

Infertility or involuntary childlessness is medically defined as the inability to achieve a pregnancy after a period of at least twelve months of regular sexual intercourse without contraception [8] . In Sub-Saharan Africa the incidence of infertility is exceptionally high in comparison to other regions in the world [2] [4] [5] . Further research indicates that in Sub-Saharan Africa at least 20% - 50% of couples of reproductive age, experience a fertility problem, and 30% are diagnosed with infertility. The incidence of infertility in South Africa is estimated at 15% - 20% of couples of reproductive age [9] . The major underlying cause of the increased incidence of infertility in Africa, may be attributed primarily to elevated incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STI’s), infections or complications following unsafe abortions and postpartum infections [2] [4] [5] [10] -[13] . In South Africa, the leading causes of infertility are tubal factor infertility (diagnosed in 57% of couples), male factor infertility (36%), and anovulation (29%) [14] . The main causes of infertility are generally divided into four main categories, namely the female factor, the male factor, combined male and female factors and unexplained, idiopathic or psychosomatic infertility [15] [16] . It is estimated that male and female factors each account for 40% while the remaining 20% are either shared or unexplained factors [17] [18] .

For many men and women, parenthood is one of the most natural progressions in adult life [19] . The assumption of trouble-free fertility may result in many couples automatically using contraceptives until they plan to start a family [20] . Ordinarily, when couples are ready to start a family, they suspend the use of all contraception, may even make a concerted effort in achieving optimal health for their prospective pregnancy. When couples experience repeated failure to conceive naturally, they tend to compare themselves with their peers that have conceived and gauge the timeframe from suspension of contraception to conception and thus use that as a guide for their own situation. It is often at this point that the couple acknowledges the significant role of the menstrual cycle. Specifically, women may diligently monitor the occurrence of ovulation as well as the non-occurrence of menses. The onset of menses is an indication of their failure to conceive. Couples who are actively trying to conceive menses are often met with feelings of shock, anxiety, devastation, loss of control and even denial of non-conception [20] [21] , while the anticipation of not having a menses results in excitement and joy. Pregnancy is viewed as exclusively a female biological occurrence. In this light, prevailing discourses have presented biological reproduction as being associated with women’s bodies; consequently fertility is viewed in terms of women, and infertility as her failure and particularly her body failing her [22] .

Since women ultimately are the ones to conceive and become pregnant, infertility is often regarded as a woman’s problem whether or not the cause has been determined to be male factor infertility [2] [4] [5] [10] [23] -[25] . In some cultures, pregnancy and motherhood represent a profound developmental milestone that is highly revered [25] . Since South Africa is a pronatalist country, women often derive their value from their reproductive abilities [26] -[28] . Since society places emphasis on the master narrative of motherhood for women, [29] childless individuals are often stigmatised [30] as they are viewed as indifferent, ineffective and culturally deviant [12] [31] .

Even though infertility is primarily dealt with medically, the psychological and emotional effects thereof are undeniable. Often when individuals discover their infertility status, they may experience emotions such as surprise, denial, anger, depression, rejection, guilt and feelings of worthlessness [32] . These are emotional reactions or manifestations of the psychological effects of infertility, which develop into what is often referred to as the “crisis of infertility” [33] . Kubler-Ross’ (1969) [34] ground-breaking work in the areas of death, grief and loss are now well recognised in grief counselling and have extended its application to various other traumatic experiences, like infertility.

Infertile women endure a myriad of felt losses and high levels of suffering and sorrow as a result of their inability to have children. Domar et al., (1993) [35] reported that infertile women revealed psychological distress levels similar to patients with grave medical conditions such as cancer, heart disease and hypertension. According to Leisewitz (1997) [36] women experience feelings of emptiness, loneliness, depression, rejection, helplessness, powerlessness and anger as emotional reactions to infertility. Infertility has also been linked to psychological problems such as low self-esteem, depression and anxiety disorders [37] . Infertility can thus be a very traumatic and tormenting time for men and women who aspire to conform to these socio-cultural conventions and who believe that childbearing is central to their lives and their identity [38] . Documented research suggests that about 40% of infertile individuals experience psychological distress associated with their condition [39] . Burns (1999) [40] revealed that anxiety and major depressive episodes are the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric problems experienced by infertile individuals, and that this incidence tends to be higher in infertile women.

In addition, women often find themselves positioned as outcasts and ostracised due their inability to have children. Involuntarily childless women may often find themselves unable to conform to the social norms of motherhood. Yet these “non-mothers” are judged according to the same standard as that of women with children as a basis for their gender and social identity [41] . Infertile women have no alternative identity, as their master narrative is that of motherhood. Consequently, infertile women often fall victim to various forms of abuse and disempowerment. Several studies [5] [7] [42] [43] emphasise the issue of the cultural construct of motherhood as important for a woman’s social, psychological and physical sense of adequacy and completeness.

This study seeks to understand the experiences of women in South Africa who are involuntary childless, and explores their psychological responses to infertility as well the effects of these responses. It is further hoped that by identifying these effects and by stimulating attention to the psychological trauma of infertility that it will create an awareness for many couples who experience it. Also, it may assist health practitioners who work with infertile couples to become more aware of the psychological and emotional experiences that infertility presents. Perhaps this awareness may assist in alleviating the psychological trauma for many infertile individuals and couples as they may feel that their feelings are validated and therefore exhibit “normal” reactions to infertility. Involuntary childless individuals find themselves unable to conform to the social norms of motherhood. With no alternative identity they tend to internalise the social scorn and ostracisation. However, by creating sufficient awareness this study can assist infertile women in understanding their experience and the need to renegotiate the meaning of the body by finding identity space for being a woman and space for being childless at the same time. For these women, the challenge lies in creating awareness and providing alternative identities; the ability to reconfigure the lens for viewing motherhood and the hegemonic ideologies of motherhood as the master identity for womanhood.

Aims and Objectives of the Study

This study explored the experiences of infertile women and understanded their struggle in their pursuit of motherhood. The primary objective of the study was to explore how infertile women understand the experience of their infertility. A secondary objective was to identify their psychological (i.e. what they think or how they understand) and emotional (i.e. how they feel) responses to infertility. By identifying these experiences of infertility the necessary recommendations may be submitted to other involuntary childless couples as well as health practitioners working with infertile couples so that these practitioners may feel encouraged to implement the recommended support structures.

2. Method

This study utilised a qualitative methodological approach as it provides personal descriptive accounts of how involuntary childless women experience infertility and also identified the psychological effects thereof. These subjective accounts provided in-depth insight into these women’s thoughts and emotions of how they experienced infertility. Also using an interpretivist framework where the role of language and discourse became central in the research process facilitated an in-depth understanding of these experiences. Applying a social constructionist theory abetted in understanding how involuntary childless women in our study interpreted, responded to and attached meaning to fertility and infertility. It also facilitated our understanding of how they made sense of these constructs in drawing meaning from discourses located within their socio-cultural context.

2.1. Study Participants

The criterion for participation in the study was that participants had to be married or at least in a committed relationship; and display either primary or secondary infertility. The snowball technique was used to recruit these participants. As potential participants were identified a screening questionnaire was used to determine whether these women matched the sample criteria. The participants were invited to a briefing session whereby they were informed about the study aims, procedures and ethical considerations. As the aim was to recruit a diverse sample, further consideration was given to the distributions of ethnic (black, white or coloured ancestry) groups, the participants’ mother tongue language/s (i.e. Afrikaans, English and Xhosa) and religion (Christian, Muslim or Indian). At least 21 women were recruited and participated in the study. Initially it was intended to recruit a sample of 30 participants however saturation point was reached at the 21st interview.

2.2. Data Collection and Study Instruments

From the onset of the study it was decided that semi-structured individual interviews would be appropriate for the study as this method of data collection allows the participants flexibility and creates space for the participants to share their story in an unrestrictive manner. The interview schedule was formulated largely based on literature and theoretical content. The key research questions were of an exploratory and descriptive nature. The questions probed specifically about their experiences of the psychological and emotional effects of infertility. Some of the questions asked were “how did you come to realise that you were having difficulty falling pregnant, what does it mean to you to be a woman, what does infertility mean to you, how did you feel when you were diagnosed as being infertile, what were your thoughts around being infertile, explain the effect infertility had on your daily functioning and your life in general”. The interview guide was pretested to ensure content validity. The duration of the interview was approximately one hour. Before the interview commenced, a debriefing session was held. In this session, informed consent was obtained, the participants were each handed a copy of the interview guide to peruse and then explained how the interview process would unfold. The final phase of the interview involved another debriefing session. The purpose of this post-debriefing session was to alleviate the strain for the participants by talking about how they felt sharing their story and how they experienced the interview. The pre and post debriefing sessions were approximately 20 minutes each. The interviews were either conducted at the participant’s home or at a neutral venue such as a local coffee and snack bar.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The ethical considerations adhered to in this study ranged from informed consent; minimization of potential harm/deprivation of benefits; and confidentiality and protection of privacy. The proposal of the research study served at the University of the Western Cape Ethics Committee and permission was granted to conduct the current study. All of the participants voluntarily participated in the study; none of the participants were coerced or manipulated into sharing their subjective experiences of infertility. The participants were given the option of withdrawing from the study at any time and also given the assurance that any questions deemed too difficult to answer could be omitted. Participants were also provided with a psychological counsellor if required.

2.4. Data Analysis

The levels of analysis embarked upon in this study were preliminary analysis, thematic analysis, coding, and interpretation. The first entry into analysis was to critically assess the data as it was collected, ascertain gaps in the information, and to commence with various concepts and establish a framework to assess if the data collected provided more information on issues relating to the research topic. Each interview transcription was read, summarized and analysed by means of developing themes. The themes that were established with the preliminary analysis were scrutinized once data had become saturated and an extensive view of the topic acquired. Each theme was placed in a specific file once it had been contextualised. There were essentially five major steps that made up the levels of analysis. The steps were; data organisation and reduction, thematic analysis, coding, interpretation and conclusion drawing.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the Sample

A total of 21 women were recruited and participated in the study. The women ranged in age from twenty six to forty-one years, with the average age being 30 years old. All of the participants are married, 15 of the participants had a post-matric qualification while the remaining six participants had a matric qualification. English was the first language for 16 of the participants, while three of the participants were bilingual with both English and Afrikaans languages, and the remaining two participants spoke Afrikaans as a mother tongue. Only four of the participants were Muslim, while the remaining 17 of the participants were Christian in religion. About 19 of the participants were employed full time, only two of the participants were unemployed. While 11 of the participants were of the white race, the remaining 10 participants were of the coloured race. Of the 21 participants recruited and interviewed, only 11 of the participants disclosed that they had received some form of counselling.

3.2. Psychological Responses to Infertility

3.2.1. Disappointment and Shock

Since fertility is often taken-for-granted, the emotions of disappointment and shock are very common. The women in this study were quite eager to conceive so they were anticipating pregnancy and engaged in close monitoring of the menstrual and ovulation cycles. In anticipating a pregnancy, the participants described emotions of excitement, joyfulness, happiness, deep satisfaction, and generally feeling in high spirits.

“We were eagerly waiting for a pregnancy every month. We were excited and happy, we were always feeling good about it, we always expected okay this month its going to happen”.

“Every month that came and gone we were just waiting to be pregnant. We would have about 2 - 3 pregnancy tests in the house with every cycle just waiting to see if it was going to be positive. At that time we were very happy, everything was good and were very satisfied with everything at the time, very keen and enthusiastic that everything would be fine.

These participants expressed their viewpoints with great conviction and sincerity, but also with humiliation and shame. However, whilst some of the participants were expressing their feelings, an undertone of anger was detected.

3.2.2. Anger and Frustration

Some of the participants shared their experiences with undertones of anger. However, the level of anger in their undertones varied from subtle to severe. These participants expressed that their inability to have a biological child has resulted in feelings of frustration and anger.

“the frustration would come and go but the anger remained and intensified.” The anger was sometimes selfinflicted because of the belief that they themselves have caused this injustice. You feel angry because nobody can give you an answer, you feel frustrated, because you are not in control anymore and you feel powerless because you can’t fix this problem. And if you feel that you are somehow to blame or that you somehow caused it then you keep the anger inside because you feel that you deserve to feel the pain and frustration”.

For this participant, living with the anger was a way of coping with the infertility because it provided her with some kind of “control” for the infertility. It was a constant reminder that their infertility was there and feeling that anger gave her some measure of control in handling the infertility. She explained that she felt powerless because she could not take control and fix the problem and that this was the only form of control she had. Mabasa’s (2002) [44] study found similar results where the participants described how their inability to take control of the situation made them feel powerless. Despite the feelings of dyscontrol and powerlessness, however hope was a constant emotion experienced.

3.2.3. Hope and Optimism

Every month was a month of new hope. In the initial stages, it was easy to raise the expectation that next month may yield a positive result. As the number of attempts increased, the level of optimism grew. But as time went by, the intensity of the disappointment outgrew the level of optimism.

“I was really very positive in the beginning and I thought you know with medical treatment you can’t go wrong. I thought of the treatment as merely a formality for one that struggles and I thought okay here we go, it won’t be long now. And as the more attempts went by I was still very optimistic, saying and really believing the next one, the next one, etc. but you know, even though I am a very positive person I must admit that I became very despondent as the more and more attempts went by”.

“Eventually I was very disappointed. [Interviewer: can you tell me more about the disappointment?] I was disappointed in myself for not responding positively physiologically, I was disappointed in the medical profession, and I was very disappointed in God. He is the one person that can make everything right, but He chose not to. It took me a long time to come to terms with God’s way. I have to continue to put my trust in Him and believe that He knows why he is doing this and that may be if it is according to His will He will grant me a baby. It is all in God’s hands now”.

“It’s not easy to keep yourself positive all the time. But I kept the faith and I kept believing that it would happen. As time went bye I just lost that belief and I started to doubt things in my life. I doubted myself as a person, as a woman, as a wife. I doubted my marriage and my relationship with God. When you are unsure about your identity, you question everything in your life”.

The participants expressed their belief in the medical treatment and their belief in God and their optimism was based on this belief. The participants explained that they kept the faith despite their struggles and failed attempts at conceiving. Every cycle presented a new hope, another opportunity to conceive and the hope and optimism was continuous. These women were serial optimist always waiting for the next cycle and the next cycle until eventually the disappointment of failed attempts transcended the hope and optimism.

The participants also demonstrated strong religious beliefs that reinforced the philosophy that children are gifts from heaven, and are privileges awarded to good women as blessings from God. The participants, at this stage, experienced an overwhelming sense of blame. This sense of blame was directed at themselves as well as other people with whom they had contact.

3.2.4. Self-Blame and Blaming Others

The participants described a strong feeling of blame and articulated a need to blame themselves, their spouses or God. They were asked to explain how they made sense of their infertility. The participants’ responses portrayed similar explanations.

“I use to think maybe I did something terribly wrong and God is taking away what I would like to so much have. Initially I use to think maybe I am a bad person or I am not worthy of a child or, you know all these feelings go through your mind. Maybe I am not going to be a good mother, maybe it is not meant for me. Sometimes I think all the weird things as well like maybe I am going to have a very short lifespan and that’s why God doesn’t want to grant me a child. All these things it goes through your mind, because you don’t know what is wrong. Generally there was no problem with my tubes, I was menstruating regularly, ovulating regularly so I did not have a physical or biological problem, it had to be something else”.

“We are women, it should be a natural process by now. I can’t make sense of it, because people fall pregnant, 16 year olds fall pregnant and I want a baby. Homeless people fall pregnant, they drink and use drugs. I don’t think any person will make sense of infertility. Especially when you know that you can provide for a child and there are so many children out there. I kept thinking about why this was happening, I kept trying to make sense of it but I couldn’t. It just didn’t make sense to me because those homeless people and 16 year olds definitely did not deserve a baby more than me. I can offer a child a good life, I am a good person. And it I don’t want a child then it is God’s will not mine, He does not want to give me a child, I don’t know why”.

In trying to understand and make sense of their infertility, the participants experienced feelings of self-blame, blame for their spouses and even God. The responses showed how the participants equated infertility with a form of punishment. It was a common practice among these participants to engage in a process of introspection in an attempt to make sense of their infertility by tracing the wrong that they might have done in the past to assess if the “punishment fit the crime”. Upon completion of this reflection, many of the participants felt that they were able to identify possible reasons for punishment. Dyer et al., (2002: 1659), found in their study that women viewed fertility as a gift from God and therefore viewed infertility as a form of punishment. One participant in their study said “maybe I am being punished for having sex before marriage”.

“I sometimes think to myself that I deserve this infertility because when I was younger I used to do things that weren’t right. I was sexually active before I was married and to top that off there was a time when I was seeing a married man and we were intimately involved. Now when I think back to that then I feel like I deserve this and brought it upon myself. The other thing that nags me is that now my husband has to suffer to”.

“When I was younger I didn’t really appreciate my body, I mean really appreciate my body. And when I think back to my young days I remember how I was quite flirtatious with the boys and things would often get out of hand. I used to like all the attention and always looked and dressed the part. I was always dressed in low tops showing off my cleavage and sexy short skirts that would get everyone talking. I liked the reaction and I liked the idea that all the boys wanted to be with me, naturally all the other girls hated my guts. Sometimes I think this is the price I have to pay for that. And when I think about it now its like a lump in my throat because I chose to show off my body and now I’m being punished with a body that doesn’t work properly. I went from having a body that everyone desired to having a body that no one wanted.

This sentiment was shared by many of the participants where a reciprocated relationship between blame and guilt became apparent. Braveman (2002: 2) [45] also found similar results in the research study where participants blamed themselves and felt guilty for having done things in the past and now felt that perhaps they were being punished. To illustrate this discourse, a participant in this study said “everyone else can get pregnant, I must have done something wrong to deserve this”.

“I tend to ask the question what did I do wrong to be punished this way. Obviously if this is happening to me then I must have done something wrong. Well, if it is punishment then I probably deserve what I’m getting, its my lot in life, I have to deal with it”.

“I do believe God have a plan for us all. In his own time he will let us have a child. Sometimes I feel God forgot about me or he is moving me down the list every time its my chance. It makes me sometimes quite angry with Him, although I can’t get angry with Him. I respect God too much for that but I’m only human. I also have wants and needs and I don’t understand why I can’t have my own child what I did that was so wrong. God know best and He must know why he is keeping me from having a child, if I did something to deserve this then I must know its my own fault and I can’t blame anyone else”.

The relationship between infertility and punishment has also become very evident in the lives of the participants as they try to make sense and understand why this has happened to them. The participants also thought of their infertility as being a form of physical deficiency whereby their body’s use and effectiveness had been diminished. This was often thought of as a result of a prior bodily misconduct, which could have been sexual promiscuity, an abortion or having multiple sexual partners. The infertility is then thought of as a form of punishment or even a life sentence for some past wrongdoing. This finding is in keeping with a study conducted by Williams, (1997) [18] , where the participants expressed a similar view that infertility was a punishment for some past wrongdoing. Subsequent to processing the “crime” and “punishment” the participants reported that they were confronted with accepting that they have fertility problem.

3.2.5. Acknowledgement

The participants progressed to a stage of acknowledgement that a problem exists. Participants reached the realisation that something had to be done to get to the bottom of the problem and to understand why they are having difficulty conceiving. This realisation stemmed from their frustration of the many months and the many monthly cycles that had gone by and missed opportunities to fall pregnant. The “need to know why” prompted acknowledgement of a problem and the pursuit of further medical investigation. Once participants were able to acknowledge the problem they described experiencing various emotions.

3.3. Stages of Emotions of the Responses to Infertility

The emotions described in the current study are similar to the Kubler-Ross grief theory of emotions. The Kubler-Ross grief theory identified five stages of emotions that one progresses through in a time of grieving and loss. These stages of grief are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. However, there are fundamental differences. The participants initially experienced disappointment and shock, anger and frustration, a deep sense of sadness and then progressed to a sense of acknowledgement. Hope and optimism were emotions experienced at each of the five stages of emotion. Previous studies [46] -[49] described various stages of emotions through which infertile people generally progressed. A common thread among these theories is that all infertile patients responded with shock, anger, depression and grieving for an intangible loss. However, there were also great disparities amongst these theories with regards to the number of stages, the time allocation for these stages, whether all infertile individuals experienced these stages and the sequence in which these emotions had been experienced. Many of these theorists based their theories on the Kubler-Ross theory of grief in direct relation to infertility.

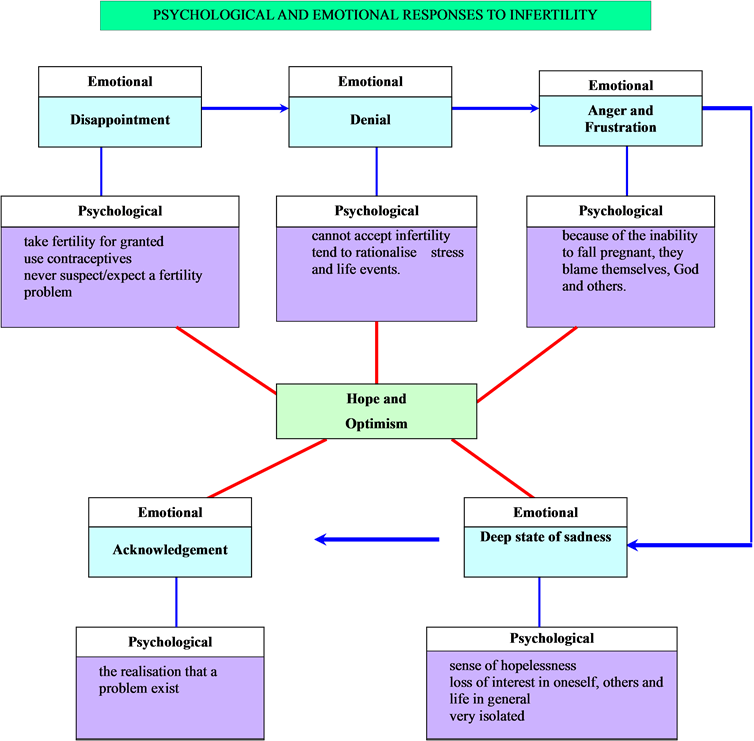

The current study proposes the following model to depict the stages of emotions that the participants progressed through in their experience with infertility. Even though this model is similar to the Kubler-Ross theory, there are essential differences. Perhaps the biggest divergence lies with stage five, which is the Acknowledgement stage. Unlike the Kubler-Ross theory where the individual accept their mortality, the participants in this study did not accept their infertility at this stage but rather only came to the realisation that a problem existed. As no medical diagnosis had been sought or made at this stage, they did not experience acceptance of infertility as such but only acknowledgement of a problem. The previous discussion described the participants’ general emotional response to infertility. The ensuing discussion presents a synopsis of the participants’ responses to infertility. The emotions described by the participants were disappointment and shock, denial, anger and frustration, deep state of sadness and acknowledgment, as well as hope and optimism being the emotions that are centrally located within each of the five emotions describes.

3.4. Explanation of Synopsis of Psychological and Emotional Responses to Infertility

Stage 1: Disappointment and Shock

Initially when the participants got married, they assumed that fertility was problem-free and therefore feared an imminent pregnancy. They used contraceptives as a means of preventing a pregnancy until they were ready to plan a family. When the participants felt they were ready to conceive they suspended the use of contraceptives, engaged in unprotected sexual activity and anticipated a pregnancy. The continued failed attempts resulted in the participants feeling disappointed and shocked by the non-conception.

Stage 2: Denial

After months of trying and failed attempts the participants lived with the feelings of disbelief and denial. They could not accept that this was happening to them and their first inclination was to attribute these failed attempts to stress and other life events that were happening at the time.

Stage 3: Anger and Frustration

In this stage the participants were experiencing feelings of anger and frustration since their attempts to conceive were futile. As the number of failed cycles increased, the intensity of anger and frustration increased. As a result of dealing with this anger they would often blame themselves, God and their spouses. The inability to take control of the problem made the participants feel helpless and powerless and this fuelled their anger.

Stage 4: Deep State of Sadness

All these negative emotions resulted in the participants slipping into a state of deep sadness. They experienced a strong sense of hopelessness, loss of self-interest, interest in others and life in general. The participants questioned the meaning of their life, their purpose and value in living a life without children. They isolated themselves from family members and friends as they felt that their feelings were not understood and that people often made insensitive comments and offered futile unsolicited advice.

Stage 5: Acknowledgement

After some time has lapsed the participants began to realise that they could no longer deny that a problem existed. As time lapsed, they began to suspect a problem and expressed that the “need to know” what the problem was for their non-conception. This need to know prompted further inquiry and the pursuance of medical intervention.

Stage 6: Hope and Optimism

The emotions of hope and optimism are presented in the centre of the diagram because these emotions are present at every stage. Even before the first phase (i.e. disappointment and shock), the participants were hopeful and optimistic that they were going to fall pregnant. At the second phase (i.e. denial), the participants could not believe that they were not pregnant and somehow were still able to drudge up hope and optimism. At the third phase, (i.e. anger and frustration), they could still find hope and optimism to move on and believe that a pregnancy is possible. At the fourth phase (i.e. deep state of sadness) amidst the gloom and despair, the participants were once again able to find hope and optimism. At the final phase (i.e. acknowledgement), the participants were able to concede that they had a fertility problem but were still hopeful and optimistic that they had viable options to motherhood.

4. Sum

In sum, the participants expressed the huge psychological strain and impact of infertility on their lives. Living with infertility in a social context where women are judged and valued for their reproductive abilities can be difficult [50] and harmful to one’s psychological and emotional well-being. The findings of this study have highlighted the severe psychological and emotional effects that accompany infertility. Therefore, for couples who are experiencing difficulty in conceiving, it is imperative to employ effective coping strategies in dealing with infertility. Also, ensuring that they have adequate support and are privy to important information that is accurate and reliable as this will provide these couples with some kind of awareness and knowledge as to what the infertility journey entails.

References

- Hazelwood, L.C. (1999) Leadership, Responsibility and Men’s Partnership with Women to Improve Reproductive Health. Mussoorie, 1-71. http://etd.uwc.ac.za/usrfiles/modules/etd/docs/etd_init_4736_1180442790.pdf

- Okonofua, F. (1999) Infertility and Women’s Reproductive Health in Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 3, 7-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3583224

- Raymond, J. (1993) The Product of Fertility and Infertility: East and West, South and North. “Women as Wombs”. Harper-Collins Publishers, San Francisco, 1-28. http://rocateo.ubbcluj.ro/studia/st_Hubel_2006_1.pdf

- Van Balen, F. and Gerrits, T. (2001) Quality of Infertility Care in Poor-Resource Areas and the Introduction of New Reproductive Technologies. Human Reproduction, 16, 215-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/16.2.215

- Inhorn, M.C. (1994) Interpreting Infertility: Medical Anthropological Perspectives. Social Science & Medicine, 39, 459-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90089-2

- Sandelowski, M. (1988) Without Child: The World of Infertile Women. Health Care Women International, 9, 147-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07399338809515814

- Ulrich, M. and Weatherall, A. (2000) Motherhood and Infertility: Motherhood through the Lens of Infertility. Feminism & Psychology, 10, 323-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959353500010003003

- World Health Organisation (2003) Infertility Definitions and Terminology. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/definitions/en/

- Martin, A. (1997) Women’s Health Project. Infertility: A Literature Review and Annotated Bibliography. Wits Press, Johannesburg.

- Abbey, A., Andrew, F.M. and Halman, J.L. (1991) Gender’s Role in Responses to Infertility. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 295-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1991.tb00798.x

- Dyer, S.J., Abrahams, N., Hoffman, M. and van der Spuy, Z.M. (2002) Infertility in South African: Women’s Reproductive Health Knowledge and Treatment-Seeking Behaviour for Involuntary Childlessness. Human Reproduction, 17, 1657-1662. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.6.1657

- Dyer, S.J., Abrahams, N., Hoffman, M. and van der Spuy, Z.M. (2002) “Men Leave Me as I Cannot Have Children”: Women’s Experience with Involuntary Childlessness. Human Reproduction, 17, 1663-1668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.6.1663

- Larsen, U. (2000) Primary and Secondary Infertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29, 80-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/29.2.285

- Wiswedel, K. and Allen, D.A. (1989) Infertility Factors at the Groote Schuur Hospital Fertility Clinic. South African Medical Journal, 76, 65-66.

- Cooper-Hilbert, B. (1998) Infertility and Involuntary Childlessness. W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., London.

- Davajan, V. and Israel, R. (1991) Diagnosis and Medical Treatment. In: Stanton, A.L. and Dunkel-Schetter, C., Eds., Infertility: Perspectives from Stress and Coping Research, Plenum Press, New York.

- Eunpu, D.L. (1995) The Impact of Infertility and Treatment Guidelines for Couple Therapy. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 23, 115-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01926189508251343

- Williams, M.E. (1997) Toward Greater Understanding of the Psychological Effects of Infertility on Women. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 16, 7-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J294v16n03_02

- Rowland, R. (1992) Dark Side of the Desire for Fertility. Guardian, 2, 16.

- Olshansky, E.F. (1987) Identity of Self as Infertile: An Example of Theory-Generating Research. Advanced Nursing Science, 9, 54-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198701000-00009

- Williams, L.S. (1990) No Relief until the End: The Physical Costs of in Vitro Fertilization. In: Overall, C., Ed., The Future of Human Reproduction, Women’s Press, Toronto, 120-138.

- Riessman, C. (2000) Stigma and Everyday Resistance Practices: Childless Women in South India. Gender & Society, 14, 111-135.

- Becker, G. and Nachtigall, R.D. (1994) “Born to Be a Mother”: The Cultural Construction of Risk in Infertility Treatment in the U.S. Social Science and Medicine, 39, 507-518.

- Bliss, C. (1999) The Social Construction of Infertility by Minority Women. Doctoral Dissertation.

- McEwan, K.L., Costella, C.G. and Taylor, P.J. (1987) Adjustment to Infertility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96, 108-116.

- Leke, R.J., Oduma, J.A., Bassol-Mayagoitia, S., Bacha, A.M. and Grigor, K.M. (1993) Regional and Geographical Variation in Infertility: Effects of Environmental, Cultural and Socioeconomic Factors. Environmental Health Perspectives, 101, 73-80.

- Blenner, J.L. (1992) Patients’ Perceptions of Infertility Treatment. American Journal of Nursing, 41, 92-97.

- Savage, O.M. (1992) Artificial Donor Insemination in Yaounde: Some Socio-Cultural Considerations. Social Science & Medicine, 35, 907-913.

- Sonko, S. (1994) Fertility and Culture in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. United Nations Educational Scientific Certified Organisation, 141, 397-411.

- Venkatesan, L. (2005) Self-Concept of Infertile Women. Nursing Journal of India, 96, 55-56.

- Beutel, M., Kupfer, P., Kehde, S., Kohn, F.M., Schroeder-Printzen, I., Gips, H., Herrero, H.J.G. and Weidner, W. (1999) Treatment-Related Stresses and Depression in Couples Undergoing Assisted Reproduction Treatment IVF or ICSI. Andrologia, 31, 27-35.

- Frediani, J.M. (1999) The Effects of Infertility on Status and Access to Resources among Wamakonde Women in Tanzania. Dissertation, University of California at Davis, Davis. www.nsf.gov/sbe/bcs/anthro/samples/borgprop.doc

- Seibel, M.M. and Taymor, M.L. (1982) Emotional Aspects in Infertility. Fertility and Sterility, 37, 137-145.

- Kubler-Ross, E. (1969) On Death and Dying. Macmillan, New York.

- Domar, A.D., Zuttermeister, P.C. and Friedman, R. (1993) The Psychological Impact of Infertility: A Comparison with Patients with Other Medical Conditions. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 14, 45-52.

- Leisewitz, W.A. (1997) Explanatory Models of Infertility. Unpublished Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Boonmongkon, P. (2002) Family Networks and Support to Infertile People. In: Vayena, E., Rowe, P.J. and Griffin, P.D., Eds., Current Practices and Controversies in Assisted Reproduction, World Health Organisation (WHO), Geneva.

- Ndaba, N. (1994) The Experiences of Infertile African Women in Durban. Unpublished Master’s Dissertation, University of Natal, Kwa Zulu Natal.

- Morrow, K.A., Thoreson, R.W. and Penny, L.T. (1995) Predictors of Psychological Distress among Infertility Clinic Patients. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 63, 163-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.1.163

- Burns, L.H. and Covington, S.N. (1999) Psychology of Infertility. In: Burns, L.H. and Covington, S.N., Eds., Infertility Counselling: A Comprehensive Handbook for Clinicians, Parthenon Publishing, New York.

- Kantor, B. (2006) A Foucaldian Discourse Analysis of South African Women’s Experience of Involuntary Childlessness. Unpublished Master Thesis, University of the Western Cape, Western Cape.

- Ponticas, Y. and Fagan, P. (1997) Issues in the Psychological Evaluation and Care of in Vitro Fertilization Couples. In: Wildes, R.W., Ed., Infertility: A Crossroad of Faith; Medicine and Technology, Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Netherlands, 27-38.

- Woollett, A. and Boyle, M. (2000) Reproduction, Women’s Lives and Subjectivities. Feminism & Psychology, 10, 307-311.

- Mabasa, L.F. (2002) The Psychological Impact of Infertility on African Women and Their Families. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Braveman, A.M. (2002) Stress and Infertility. Healthology Fertility Focus. http://www.Healthology.com

- Nija, P. and Rouffa, L. (1975) AID Couples: Psychological and Psychopathological Evaluation. Andrologia, 7, 187.

- Menning, B.E. (1982) The Psychosocial Impact of Infertility. Nursing Clinics of North America, 17, 155-163.

- Renne, D. (1977) There Is Always Adoption: The Infertility Problem. Child Welfare, 34, 861-871.

- Keye Jr., W.R. (1999) Infertility: Is There a Role for the Surgeon. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 43, 929-941. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003081-200012000-00022

- Benyamini, Y., Gozlan, M. and Kokia, E. (2005) Variability in the Difficulties Experienced by Women Undergoing Infertility Treatment. Fertility and Sterility, 83, 275-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.014