Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

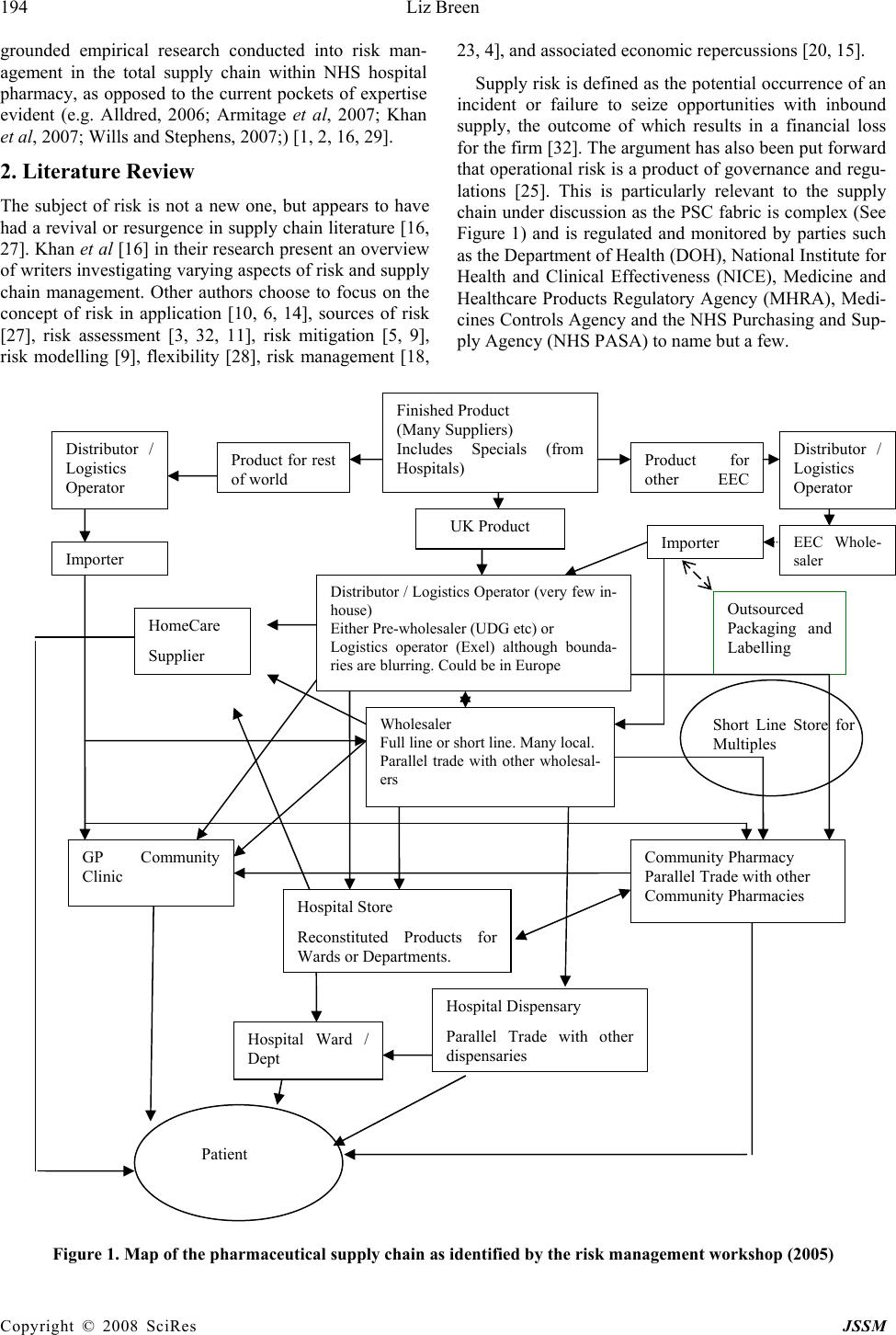

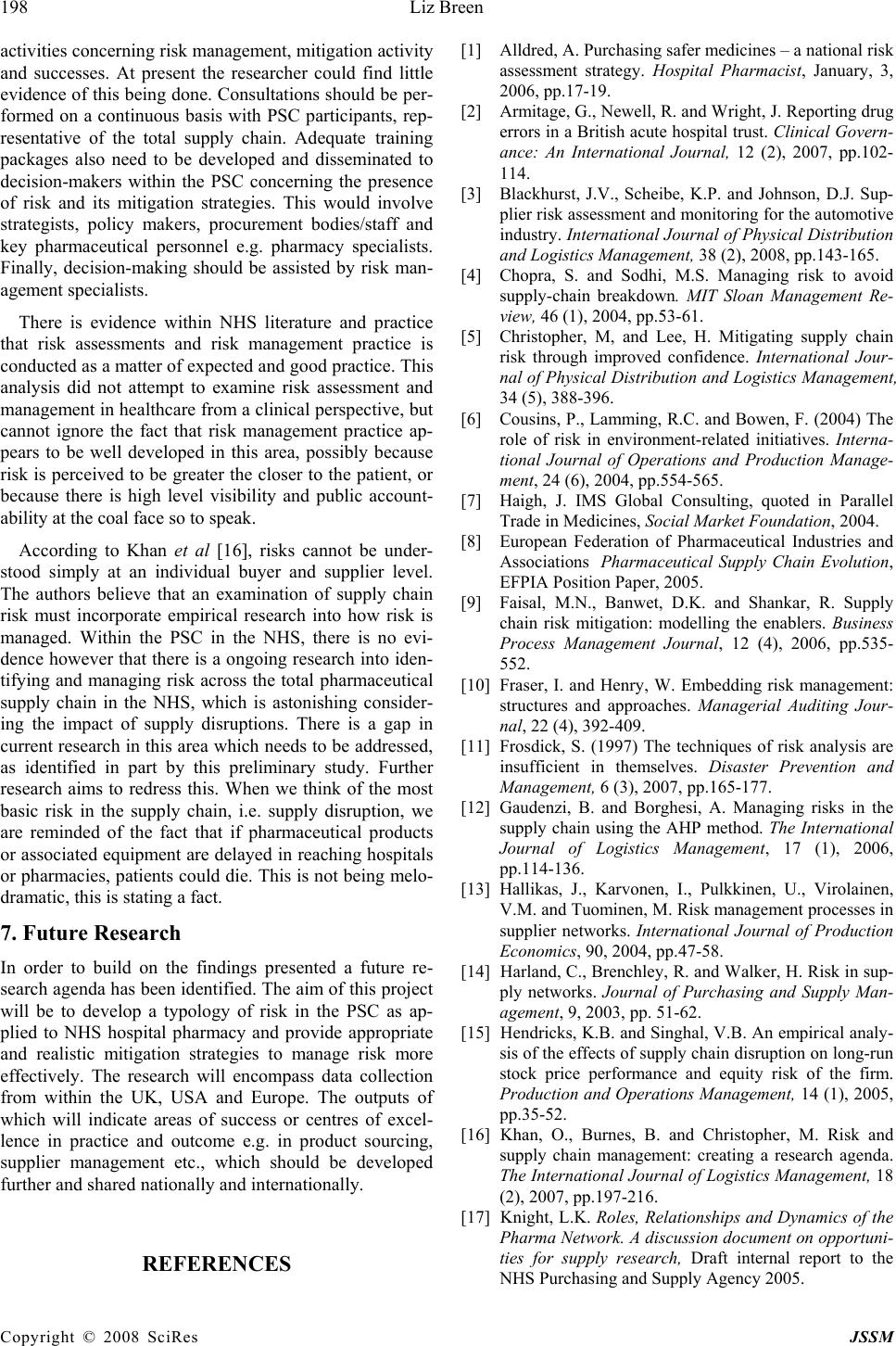

J. Serv. Sci. & Management, 2008, 1: 193-199 Published Online August 2008 in SciRes (www.SRPublishing.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM A Preliminary Examination of Risk in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain (PSC) in the National Health Service (NHS) (UK) Liz Breen Bradford University School of Management, Emm Lane, Bradford, West Yorkshire, BD9 4JL E-mail:l.breen@bradford.ac.uk ABSTRACT The effective management of pharmaceuticals in the National Health Service (NHS) is critical to patient welfare thus any risks attached to this must be identified and controlled. At a very basic level, risks in the pharmaceutical supply chain are associated with product discontinuity, product shortages, poor performance, patient safety/dispensing errors, and technological errors (causing stock shortages in pharmacies) to name but a few, all of which incur risk through disruption to the system. Current indications suggest that the pharmaceutical industry and NHS practitioners alike have their concerns as to the use of generic supply chain strategies in association with what is perceived to be a spe- cialist product (pharmaceuticals). The aim of the study undertaken was to gain a more realistic understanding of the nature and prevalence of risk in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain (PSC) to be used as a basis for a more rigorous research project incorporating in- vestigation in the UK, Europe and USA. Data was collected via a workshop forum held in November 2005. The outputs of the workshop indicated that there were thirty-five prevalent risks. The risks were rated using risk assessment catego- ries such as impact, occurrence and controllability. The findings indicated that the risks identified are similar to those prevalent in industrial supply chains, regardless of the idiosyncrasies of pharmaceuticals. However, the group consen- sus was that caution must be applied in how such risks are addressed, as there are aspects of the product that highlight its uniqueness e.g. criticality. Keywords: pharmaceutical supply chain, risk management 1. Introduction According to Khan et al “Risk is an ever-present aspect of organisational life” [16] and “ there is a need to de- vise robust and well-grounded models of supply chain risk management, which incorporate risk management tools and techniques from other disciplines of research [16]”. Whilst this may be the case, there has been no re- search to date, which has investigated risks within the total PSC as pertinent to NHS pharmacy. It is vital to do so because pharmaceuticals are a core input into health- care treatment and are critical products. The authors above would support this sentiment arguing that risk management has only recently been seen as an issue that urgently needs to be addressed in supply chain manage- ment. Academic researchers and practitioners believe that “pharmaceuticals are different; they cannot be treated like other commodities” [24]. The reasons for this senti- ment were the high cost and long duration for research and development and the repercussions of the product not being available, hence again its criticality. Other unsup- ported perception-based factors that appear to make this supply chain distinctive include; the level of regulation in the product production, storage, distribution, consump- tion and the complexity of the fabric of this supply chain [17]. Research conducted by Blackhurst et al [3] devel- oped a risk framework based on that formulated by Cho- pra and Sodhi [4], but it had to be customised further to incorporate industry idiosyncrasies. This may also be an option for the PSC in the NHS (UK). It would appear, purely from the research findings, that there is concern as to the growing number of risks within the PSC, and the lack of co-ordinated effort in assessing and managing them. This is worrying as the purpose of the PSC is to source pharmaceuticals and materials that can be moved through the supply chain to provide treat- ment to the end-user. Risks have been identified by this research, which would negatively affect the performance of the total supply chain (from raw material sourcing through to dispensation of medication). This paper aims to highlight this issue, identifying the nature and prevalence of risk, as determined by supply chain users. The paper will conclude by stating that there needs to be a more co-ordinated approach to and  194 Liz Breen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM grounded empirical research conducted into risk man- agement in the total supply chain within NHS hospital pharmacy, as opposed to the current pockets of expertise evident (e.g. Alldred, 2006; Armitage et al, 2007; Khan et al, 2007; Wills and Stephens, 2007;) [1, 2, 16, 29]. 2. Literature Review The subject of risk is not a new one, but appears to have had a revival or resurgence in supply chain literature [16, 27]. Khan et al [16] in their research present an overview of writers investigating varying aspects of risk and supply chain management. Other authors choose to focus on the concept of risk in application [10, 6, 14], sources of risk [27], risk assessment [3, 32, 11], risk mitigation [5, 9], risk modelling [9], flexibility [28], risk management [18, 23, 4], and associated economic repercussions [20, 15]. Supply risk is defined as the potential occurrence of an incident or failure to seize opportunities with inbound supply, the outcome of which results in a financial loss for the firm [32]. The argument has also been put forward that operational risk is a product of governance and regu- lations [25]. This is particularly relevant to the supply chain under discussion as the PSC fabric is complex (See Figure 1) and is regulated and monitored by parties such as the Department of Health (DOH), National Institute for Health and Clinical Effectiveness (NICE), Medicine and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), Medi- cines Controls Agency and the NHS Purchasing and Sup- ply Agency (NHS PASA) to name but a few. Figure 1. Map of the pharmaceutical supply chain as identified by the risk management workshop (2005) Wholesaler Full line or short line. Many local. Parallel trade with other wholesal- ers Finished Product (Many Suppliers) Includes Specials (from Hospitals) UK Product Product for o th e r EE C Distributor / Logistics Operator EEC Whole- sale r Im p orte r Outsourced Packaging and Labelling Distributor / Logistics Operator (very few in- house) Either Pre-wholesaler (UDG etc) or Logistics operator (Exel) although bounda- ries are blurring. Could be in Europe Product for rest o f wo rl d Distributor / Logistics Operator I m p orte r Community Pharmacy Parallel Trade with other Community Pharmacies GP Community Clinic Hospital Store Reconstituted Products for Wards or De p artments. Short Line Store for Multiples Hospital Dispensary Parallel Trade with other dis p ensaries Patient Hospital Ward / Dept HomeCare Supplier  A Preliminary Examination of Risk in the Pharmaceutical Supply 195 Chain (PSC) in the National Health Service (NHS) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Cousins et al [6] purport that supply chain risk comes in two forms: technological risk and strategic risk. Both types focus on an over-reliance and hence increased po- tential risk from product, process and technology and suppliers. At a very basic level, risks in the PSC are asso- ciated with product discontinuity, product shortages [17], poor performance, patient safety/dispensing errors, tech- nological errors (causing stock shortages in pharmacies), internet pharmacies and counterfeit drugs; all of which cause delays in the system and cause anguish to the final users, the patients. All of these fall into the categories proposed by Cousins et al [6]. Costs associated with mis- management of risks are also the focus of many authors e.g. Papadakis, 2006 and Hendricks and Singhal, 2003. Within the PSC, medication errors alone equate to £200- 400 million per year in the UK, and to this must be added the unknown cost of errors in primary care and litigation [19]. Tang and Tomlin [28] assert that due to the spread and complexity of supply chains they are usually slow to re- spond to environmental changes and thus are less robust when faced with business disruptions. Like such busi- nesses, there is evidence to suggest that the convoluted nature of the PSC in the NHS (UK) is similar to pharma- ceutical supply chains in other countries, and similar is- sues exist such as counterfeit medications, product short- ages etc. [30]. Research has indicated that in Europe medicines can travel through as many as 20-30 pairs of hands before it finally reaches the patient [7]. The supply chain has now become more fragmented with effectively 25 pharmaceutical markets in Europe, which has led to a decrease in transparency in the supply chain [8]. The structure of the PSC is such that an examination focusing on risk needs to encompass the complete supply chain and composite network of buyers and suppliers. In which case the total supply chain needs to be the subject of assessment as opposed to individual entities or parties e.g. risks attached to a supplier or purely to patients. Adopting a broad and encompassing view on this issue and not focusing on individual entities is critical in exam- ining this area [16]. 3. Methodology The aim of this research study was to gain a more realistic understanding of the nature and prevalence of risk in the PSC. In order to do this a workshop was held in Novem- ber 2005 focussing on risk identification within the PSC. This was attended by twenty key PSC stakeholders in- cluding pharmaceutical suppliers and wholesalers, NHS professionals and government bodies. The attendees were split into two distinct groups which contained a mix of pharmaceutical manufacturers and wholesalers and NHS personnel. The two groups were facilitated by NHS pharmacy procurement specialists. The groups were asked to deliver key objectives; these being to identify risks in the PSC, to rate their criticality and to produce an agreed map of the structure of the PSC. Both groups worked individually and were brought back together for interim group sessions (IGS) to deliver their outputs. A consensual set of data was then compiled by the researcher in the presence of the total group, based on their views and comments. At each IGS discussion was generated in order to validate or explain outputs. After a comprehensive list of risks had been identified the individual groups reconvened to apply a criticality rating. The criteria used to develop such ratings were standard of those currently used within the PSC i.e. im- pact, control and occurrence. Again, during the IGS there was some discussion and movement on the ratings, and a comprehensive list was compiled. As this study was a preliminary investigation into this area, further extrapola- tion and development of the risk ratings was not con- ducted. Further examination using tools such as model- ling or Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) could be ap- plied using the ratings identified to assist in more struc- tured decision making [12]; however as this was a pre- liminary investigation they were not employed at this stage in the study. Further discussion took place concerning the structure of the PSC. Due to time constraints the final map was completed after the workshop by an NHS pharmacy pro- curement specialist, but circulated to the workshop group for further comments and amendments. However, no amendments were requested. It was felt that a workshop was the most appropriate approach to adopt in collating the necessary data as there was a lack of published data on this subject, and the data produced would be accurate and timely. As a cross-section of companies were in- volved (17 companies/organisations represented) then a tentative assumption could be made that the findings would be more representative of opinion on this subject within this field than not. 4. Results The outputs of the workshop indicated that there were 35 prevalent risks (See Table I for summary); with varying levels of criticality and that the structure of the PSC map was product-dependent, so taking a specific product into consideration the map profile could be substantially dif- ferent. It was agreed that the top 10 risks identified were representative of the state of play in the PSC. The top rated risks included fragmentation of the supply chain (multiple channels leading to poor communication); lack of visibility concerning placement and availability of stock, inappropriate forecasting conducted by the cus- tomer and a general inability of capacity to meet demand. An outlying risk that was debated on the day was that of counterfeit medication. One member of the group was  196 Liz Breen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Table 1. Risks identified and associated ratings Risk Rating Risk Rating Fragmentation of SC – no single source, multi- ple channels, no communication, unilateral decisions 10 Too much information 6.5 Lack of visibility of stock 9 Short term SC planning 6.5 Unexpected increase in demand 8.5 Operational in/efficiencies e.g. systems operating prop- erly 6 Demand versus Capacity 8.5 Non standard practice – customised policies per hospital. Lack of common codes etc 6 Information flow or lack of information 8.5 Counterfeiting 6 Lack of forecasting – customer side 8.5 Increase in demand due to NICE approval, patient in- volvement, press 6 Availability of raw material – true and com- mercially induced. Regulatory issues – manu- facturing licensing/change of standards/drug recalls 8 Rationalisation of range 5.5 Demand/economics – not able to respond to demand 8 Cash flow/cash management – threat associated with small companies and hospitals 5.5 Inadequate buffer stock – JIT/lean 8 Storage/cold chain 5.5 Contracting treated as a commodity – big con- tracts equals big risk. Drive competitors out of market 8 Reimbursement policies not consistent 5.5 Transportation – unavailability of fuel, conges- tion, weather, illness 7.5 Response of industry to shortages – communication 5.5 Manufacturer defence tactics 7.5 Loss of expertise – unsophisticated purchasing/practice? 5 Diversion of manufacturing capacity 7.5 Risk of litigation – influence on market 5 External influences – disaster recovery 7.5 Lack of knowledge regarding manufacturing process or source of supply 4.5 Stock holding – more concentrated 7 Procurement Hubs – introduce more complexity 4.5 Exploitation 6.5 Theft 4.5 Dispensing/picking error – medica- tion/packaging, prescription management 6.5 Prioritisation – conflict between patients/profits 4 Decrease in capacity linked to profit 6.5 adamant that the risk attached to this activity was greater than the rest of the group perceived it to be. This risk was placed as 23 out of 35. The findings indicated that the risks identified are simi- lar to those prevalent in industrial supply chains crossing various categories e.g. financial, legal and operational, regardless of the idiosyncrasies of pharmaceuticals. How- ever, the group consensus was that caution must be ap- plied in how such risks are addressed, as there are aspects of the product that highlight its uniqueness e.g. criticality. Similar analysis was conducted by Blackhurst et al [3] into the automotive industry, the focus however being on supplier risk assessment and monitoring. An outcome of this study was the acknowledgement that a standard risk framework did not fit that company in that industry and therefore a standard tool had to be customised for the purpose of the research. 5. Discussion The ratings produced were based on the following criteria; control, occurrence and impact. The risks identified fall into typical risk categories such as legal, operational, fi- nancial and strategic, all of which need to be addressed to achieve effective risk management [26]. A high rating indicated a greater potential for a more detrimental impact (financial or other) on the PSC thus needing more struc- tured recovery mechanisms. The findings can be discussed in three distinct sections: Supply chain structure - The highest ranked rating was due to the fragmentation of the supply chain (10/10). The group felt that there was a lack of uniformity in decision- making within the PSC which led to such problems, and affected the efficacy of the complete supply chain. This being the case, this was a risk that needed to be addressed urgently as it affected all parties and could result in finan- cial loss. This view further supports the concerns within the industry of the increasing involvement of suppliers,  A Preliminary Examination of Risk in the Pharmaceutical Supply 197 Chain (PSC) in the National Health Service (NHS) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM manufacturers, parallel importers, generics, and whole- salers to name a few. As there are numerous players and communications within the PSC, the supply chain would benefit from hav- ing a coordinating body that is responsible for setting targets and meeting deadlines, and implementing strategy. This body needs to recognise the interconnectivity be- tween members of this network and aim to support and nurture this, whilst ensuring that risk is not passed from one party to another [13]. Attention must also be paid to instigating mitigation strategies that positively impact on the total supply chain (all entities) and not exacerbate risk as a repercussion of the initial activity. In the case of the PSC, mitigating a risk attached to a product line should not increase the risk associated with another product line, or the relationship between the buyer and supplier. Controllability – On looking at the risks presented it is clear that a certain number of risks proposed are opera- tional and functional and are therefore within the control of the industry e.g. visibility of stock, communication channels, capacity management issues and information flow. This being the case, there is a need for more effec- tive management of these risks. The industry is less capa- ble of controlling other risks e.g. counterfeiting. This was rated as a 6/10, which is still high risk but was not con- sidered high priority due to the low frequency in its oc- currence. This is such a present threat that a new group (European Alliance for Access to Safe Medicines) was launched late 2007 “to campaign for the exclusion of counterfeit medicines from the supply chain” (Pharma Anti-Counterfeiting, 1:2008). Governmental influences are also less controllable e.g. the conflict between patients and profits, NICE, and the introduction of Procurement Hubs (Collaborative Procurement Organisations) whilst others are totally uncontrollable e.g. unavailability of fuel and natural disasters and illness. In reviewing the risks produced, it can be assumed that some of the risks can effectively be addressed through better co-ordination and management of the PSC and some through effective miti- gation strategies as and when they arise. Strategy – The findings of this research indicate that there are clearly identifiable risks in the NHS PSC (UK) as determined by industry practitioners. The practitioners were also in agreement that although there is an emphasis on risk from the various agencies, companies and the NHS itself, there is no co-ordinated strategy which gov- erns risk across all the supply chain parties. Anecdotal evidence would suggest that even though practitioners know that there is risk attached to core activities within the PSC e.g. procurement contracting, there is no actual risk assessment conducted on suppliers to ascertain the level of risk in a proposed contractual relationship (a key risk being the potential to disrupt supply). Decision- making appears to reside with experienced members of staff; pharmaceutical experience not risk management. According to Blackhurst et al [3], like issues, e.g. sup- plier disruptions, led to their investigation into supplier risk assessment and monitoring and development of a risk factor framework. Disruptions within the supply chain are a major source of risk. The findings from the risk management workshop indicated that supply disruptions could be seen in the form of availability of raw materials, transportation, dis- aster recovery, lack of knowledge regarding the source of supply, rationalisation of product range and theft. Any of these could restrict or stop the flow of products through the supply chain, increasing the risk to the patient. 6. Conclusions The aim of this research study was to gain a more realistic understanding of the nature and prevalence of risk in the PSC as a preliminary research exercise. The approach adopted was qualitative and exploratory in nature. The aim was realised through the collation of data from a risk management workshop. Risk analysis in the PSC in the NHS (UK) is of key importance and has a valuable input into both practice and policy; therefore research into bet- ter understanding and management of this is justified. It affects not only the practitioners and policy makers, but also the public, as current and future users of this service. Further investigation conducted within this area could yield the following benefits; a grounded empirical re- search study, greater visibility of pharmaceutical supply chain activities and players, identification and rating of risks, more structured planning ability to strengthen prac- tice and systems, informed contingency/recovery plan- ning, more effective management of the impact of high severity events on recipients, e.g. unknown disasters, and reduce the impact of low severity events such as a break- down in buyer-supplier relationships. However, whilst some of the industry seems to be very active in pursuing this subject, others do not seem to join in their enthusiasm. The twenty contributors to the risk management workshop were representative of a cross- section of this supply chain, thus their views are represen- tative of general feeling and concern regarding the level of risk attached to key issues. The views produced were consensual, the key issues and ratings discussed and agreed by the whole group. This is evidence that despite the complexity of the PSC there is a willingness to come together as a joint body to discuss topical matters. This activity was co-ordinated by a neutral party (University of Bradford School of Management) who were impartial in the proceedings. From the research findings recommendations can be made to develop policy and practice within this area. These include adopting a structured approach to under- standing the nature of risk in the total pharmaceutical supply chain in order to effectively manage it. This would involve detailed analysis of the various party and agency  198 Liz Breen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM activities concerning risk management, mitigation activity and successes. At present the researcher could find little evidence of this being done. Consultations should be per- formed on a continuous basis with PSC participants, rep- resentative of the total supply chain. Adequate training packages also need to be developed and disseminated to decision-makers within the PSC concerning the presence of risk and its mitigation strategies. This would involve strategists, policy makers, procurement bodies/staff and key pharmaceutical personnel e.g. pharmacy specialists. Finally, decision-making should be assisted by risk man- agement specialists. There is evidence within NHS literature and practice that risk assessments and risk management practice is conducted as a matter of expected and good practice. This analysis did not attempt to examine risk assessment and management in healthcare from a clinical perspective, but cannot ignore the fact that risk management practice ap- pears to be well developed in this area, possibly because risk is perceived to be greater the closer to the patient, or because there is high level visibility and public account- ability at the coal face so to speak. According to Khan et al [16], risks cannot be under- stood simply at an individual buyer and supplier level. The authors believe that an examination of supply chain risk must incorporate empirical research into how risk is managed. Within the PSC in the NHS, there is no evi- dence however that there is a ongoing research into iden- tifying and managing risk across the total pharmaceutical supply chain in the NHS, which is astonishing consider- ing the impact of supply disruptions. There is a gap in current research in this area which needs to be addressed, as identified in part by this preliminary study. Further research aims to redress this. When we think of the most basic risk in the supply chain, i.e. supply disruption, we are reminded of the fact that if pharmaceutical products or associated equipment are delayed in reaching hospitals or pharmacies, patients could die. This is not being melo- dramatic, this is stating a fact. 7. Future Research In order to build on the findings presented a future re- search agenda has been identified. The aim of this project will be to develop a typology of risk in the PSC as ap- plied to NHS hospital pharmacy and provide appropriate and realistic mitigation strategies to manage risk more effectively. The research will encompass data collection from within the UK, USA and Europe. The outputs of which will indicate areas of success or centres of excel- lence in practice and outcome e.g. in product sourcing, supplier management etc., which should be developed further and shared nationally and internationally. REFERENCES [1] Alldred, A. Purchasing safer medicines – a national risk assessment strategy. Hospital Pharmacist, January, 3, 2006, pp.17-19. [2] Armitage, G., Newell, R. and Wright, J. Reporting drug errors in a British acute hospital trust. Clinical Govern- ance: An International Journal, 12 (2), 2007, pp.102- 114. [3] Blackhurst, J.V., Scheibe, K.P. and Johnson, D.J. Sup- plier risk assessment and monitoring for the automotive industry. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 38 (2), 2008, pp.143-165. [4] Chopra, S. and Sodhi, M.S. Managing risk to avoid supply-chain breakdown. MIT Sloan Management Re- view, 46 (1), 2004, pp.53-61. [5] Christopher, M, and Lee, H. Mitigating supply chain risk through improved confidence. International Jour- nal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 34 (5), 388-396. [6] Cousins, P., Lamming, R.C. and Bowen, F. (2004) The role of risk in environment-related initiatives. Interna- tional Journal of Operations and Production Manage- ment, 24 (6), 2004, pp.554-565. [7] Haigh, J. IMS Global Consulting, quoted in Parallel Trade in Medicines, Social Market Foundation, 2004. [8] European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Evolution, EFPIA Position Paper, 2005. [9] Faisal, M.N., Banwet, D.K. and Shankar, R. Supply chain risk mitigation: modelling the enablers. Business Process Management Journal, 12 (4), 2006, pp.535- 552. [10] Fraser, I. and Henry, W. Embedding risk management: structures and approaches. Managerial Auditing Jour- nal, 22 (4), 392-409. [11] Frosdick, S. (1997) The techniques of risk analysis are insufficient in themselves. Disaster Prevention and Management, 6 (3), 2007, pp.165-177. [12] Gaudenzi, B. and Borghesi, A. Managing risks in the supply chain using the AHP method. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 17 (1), 2006, pp.114-136. [13] Hallikas, J., Karvonen, I., Pulkkinen, U., Virolainen, V.M. and Tuominen, M. Risk management processes in supplier networks. International Journal of Production Economics, 90, 2004, pp.47-58. [14] Harland, C., Brenchley, R. and Walker, H. Risk in sup- ply networks. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Man- agement, 9, 2003, pp. 51-62. [15] Hendricks, K.B. and Singhal, V.B. An empirical analy- sis of the effects of supply chain disruption on long-run stock price performance and equity risk of the firm. Production and Operations Management, 14 (1), 2005, pp.35-52. [16] Khan, O., Burnes, B. and Christopher, M. Risk and supply chain management: creating a research agenda. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 18 (2), 2007, pp.197-216. [17] Knight, L.K. Roles, Relationships and Dynamics of the Pharma Network. A discussion document on opportuni- ties for supply research, Draft internal report to the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency 2005.  A Preliminary Examination of Risk in the Pharmaceutical Supply 199 Chain (PSC) in the National Health Service (NHS) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM [18] Manuj, I and Mentzer, J.T. Global supply chain risk management strategies. International Journal of Physi- cal Distribution and Logistics Management, 38 (3), 2008, pp.192-223. [19] Matthew, L. and Bain, T. Bridging the Gap. Patient Safety: the role of the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) in helping pharmacists to improve patient safety. Pharmacy Management, 22 (3), 2006, pp.2-8. [20] Papadakis, I. Financial performance or supply chains after disruptions: an event study. Supply Chain Man- agement: An International Journal, 11 (1), 2006, pp.25-33. [21] Pharma Anti-Counterfeiting News Launch of a New European Safe Medicines Group, (3), 2008, pp.1-4. [22] Peck, H., Drivers of supply chain vulnerability: an in- tegrated framework. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 35 (4), 2005, pp.210-232. [23] Ritchie, B. and Brindley, C. Supply chain risk management and performance. A guiding framework for future development. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 27 (3), 2007, pp.303-322. [24] Savage, C.J., Roberts, K.J., and Wang, X.Z. A holistic analysis of pharmaceutical manufacturing and distribu- tion: are conventional supply chain techniques appro- priate? Pharmaceutical Engineering July/August, 2006, pp.10-18. [25] Smallman, C. Knowledge management as Risk man- agement: A Need for Open Governance? Risk Man- agement, an International Journal, 1 (4), 1999a, pp.7- 20. [26] Smallman, C. The Risk Factor Financial Times Master- ing Management Review, 30, 1999b, pp.42-45, Decem- ber. [27] Smallman, C. Risk and organisational behaviour: a research model. Disaster Prevention and Management, 5 (2), 1996, pp.12-26. [28] Tang, C. and Tomlin, B. The power of flexibility for mitigating supply chain risks. International Journal of Production Economics, doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2008.07.008. [29] Wills, S. and Stephens, M. How safe is information about medicines? A risk assessment framework. Clini- cal Governance: An International Journal, 12 (1), 2007, pp.2-37. [30] World Health Organisation Counterfeit medicines. Ac- cessed: 12/1/07, 2006. [31] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs275/es/. [32] Zsidisin, G., Melnyk, S.A., Ragatz, G.L. and Burns, L.A. Preliminary findings from a supply risk audit in- strument. Proceedings to IPSERA Conference, Paper 43, 2006. |