Technology and Investment

Vol. 3 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 24853 , 11 pages DOI:10.4236/ti.2012.34038

Ghana Cocoa Industry—An Analysis from the Innovation System Perspective

1Science and Technology Policy Research Institute (STEPRI), Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Accra, Ghana

2CSSVD-CU (COCOBOD), Hohoe VR, Ghana

Email: goessegbey@csir-stepri.org, goessegbey@hotmail.com, ofogyamfi@hotmail.com, ofogyamfi@gmail.com

Received June 12, 2012; revised July 12, 2012; accepted July 19, 2012

Keywords: Cocoa; Innovation System; Critical Actors; Policy Reforms; Value Addition; Ghana

ABSTRACT

This paper discusses Ghana’s cocoa industry from the innovation systems perspective. Cocoa is the major cash crop of Ghana. Its importance is not only in the contribution of about 25% annually of the total foreign exchange earnings but also on account of being the source of livelihoods for many rural farmers and the related actors in the value chain. The critical actors in the innovation system are the farmers, the researchers, the buyers, the transporters, public officers, consumers and the policy makers. By the roles and functions they perform, they impact on the dynamics of the cocoa industry. The paper describes the trends in cocoa production and processing and highlights the key characteristics and implications. It discusses the policy reforms in the cocoa industry and the major drivers of the reforms. The Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) is one of the biggest public institutions in Ghana and its subsidiaries are major actors in the production process of cocoa for export. The key reforms in the policies governing the industry were the dissolution of the monopoly of Produce Buying Company and the deregulation of cocoa purchasing to allow Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs) to enter the business in 1992/93 crop season. There was also the dismantling and re-organization of the Cocoa Services Division into two separate units—the Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus Disease Control Unit (CSSVDCU) and the Seed Production Unit (SPU). The processing of cocoa into cocoa butter, cocoa paste and confectioneries is an important component of the value chain especially with the national goal of processing 50% of cocoa before export. The paper discusses policy implementation in the cocoa industry underscoring the successes and failures. It highlights lessons for other primary commodity producing countries especially those whose development contexts are similar to Ghana’s.

1. Introduction

Ghana was until the 1970s the leading world producer of cocoa. It was the highest foreign exchange earner for Ghana even as far as constituting about 45% in the 1960s. Even until the 1990s, cocoa’s share of the country’s total export earnings averaged about 35% annually. Currently, the annual percentage share has dropped to about 25% [1]. Yet, it remains the most important economic crop for the nation. The political economy of cocoa surpasses that of any other commodity the country is exploiting. Six of the ten regions of Ghana grow the crop, which for many households constitute the fundamental capital base for income and employment. It is generally known that about 90% of cocoa produced the world over comes from smallholder farms varying in size up to 5 hectares. The situation is no different in Ghana making the commodity an instrumental vehicle for lowering poverty incidence in the cocoa growing areas and providing employment for a fairly wide range of skilled and unskilled labour.

When Tetteh Quarshie brought the Amelonado cocoa bean into the then Gold Coast from Fernando Po (now Equitorial Guinea) in 1876 to establish his own plantation, he probably did not foresee the dominance the bean would have in the country’s economic life. It has grown rapidly to assert itself as one of the pillars of the country’s economy. How the trend has continued in the last two decades, the drivers of change and innovation accounting for cocoa maintaining its enviable position at the top of all agricultural commodities is the crux of this paper. From the innovation system perspective, the paper analyses the experiences, the reforms and the outcomes of the cocoa industry to provide policy options for developing economies sharing similar endowments.

The paper, which is the outcome of mainly desk research and some interviews with key informants, is organised into six sections. The introductory Section 1 emphasises the importance of cocoa in Ghana’s economy and Section 2 presents the conceptual framework. Section 3 applies key aspects of the conceptual framework to highlight the roles and relationships of the critical actors in the cocoa innovation system. Section 4 analyzes trends in production and value addition. Section 5 discusses pertinent issues relating to further development and growth of the cocoa industry and Section 6 presents the conclusion.

2. The Conceptual Framework (Heading 2)

Innovation system comprises a network of critical actors interacting in a given geographical or sectoral setting to apply knowledge and information producing innovations to address socio-economic problems or needs in context [2-5]. Such knowledge may not necessarily be new outside of the setting or even in the context of use. However, new ways of application and development emerge relative to the socio-economic needs and aspirations, leading to innovations. Innovation entails processes and products, tangible and intangible. The salient characteristics of any innovation system are the critical actors, the relationships between the critical actors and the context of innovation. The relationships are invariably defined by the responses to environmental or contextual factors and stimuli. It is important to assume the systemic perspective for analysis of development issues in relation to the cocoa industry since as far as Ghana is concerned, cocoa is a pillar in national development planning. Figure 1 depicts the critical actors and the influencing factors from the internal and external environments and their converging impact on the cocoa industry.

In applying the innovation system to the cocoa industry, Figure 1 describes the cocoa innovation system and presents an analytical framework for discussing the trends, and innovations in the industry. The critical actors as highlighted, including the public institution COCOBOD, the cocoa farmers, the processing companies and the scientific institutions. External and internal factors affect the dynamics in the system. It is necessary to discuss more summarily, the roles and activities of the critical actors as done in the next section.

3. The Critical Actors and Their Roles, Functions and Relationships (Heading 3)

The analysis of trends and innovations begins with the description of the critical actors, their roles and their functions. How they relate to each other and the strength or weakness of the relationships is important for achieving the overall goals and objectives stated for the sector. The specific roles and functions expressing how the critical actors and their roles impact on the industry are detailed in Table 1.

The analysis of the impact of the critical actors on the

Figure 1. Diagram of the cocoa innovation system—Critical actors and influencing factors.

Table 1. The critical actors and their roles and functions in the cocoa innovation system in Ghana.

cocoa industry is qualitative. However, the estimation entails the consideration of the key criteria of the roles and functions performed, the effectiveness of performance reflecting in achievement of institutional goals and objectives and, the relation of achievements to national development. Implicit in the analysis is the evaluation of the strength or weakness of linkages with relevant actors in the system. The reviews of annual reports, use of secondary data and discussion with key informants, enable such estimation to be made. The importance of Table 1 is much less in the robustness of the methodology as in the illustration of the relative strengths of institutional functions. From the innovation system perspective, it points to which institutions need to be strengthened to ensure greater innovation. The following sub-sections discuss each of these critical actors listed in Table 1, the roles, functions and relationships.

3.1. Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MOFEP)

In Ghana, MOFEP is perhaps the ministry with the most onerous responsibility. It oversees national budgeting and is responsible for resource allocation. Given the limited resources at the disposal of the state, the responsibility of MOFEP in resource allocation is not an easy one. For example, consistently Ghana’s total export revenue has been below total imports value. In 2010, the total merchandise exports value including that of cocoa for Ghana was about $7.9 billion as against imports of $10.7 billion [1]. Revenue mobilization in Ghana has its own challenges and even as government’s revenue as a percentage of GDP increased from 26.23% in 2009 to 29.27% in 2010, it is still not as would adequately support allocation of resources to public institutions as these institutions have budgeted. In fact, actual government revenue excluding grants in 2010 fell short by about 7 percent of the estimated budgeted of roughly $5.5 billion [1]1. The task of resource allocation is therefore herculean and places MOFEP in a difficult position even as it makes it a powerful ministry.

The entire cocoa industry falls within MOFEP’s remit. Fortunately for cocoa, the industry is highly prioritized and therefore the cocoa institutions are among those receiving the highest attention in resource allocation. Still its relationship with the relevant actors in the cocoa industry, especially the public institutions may not be exceptionally excellent given that allocation of resources cannot always be as demanded by the institutions.

3.2. Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD)

The Ghana Cocoa Board established in 1947 has had a long history of overseeing the cocoa sector of Ghana. It has undergone various transformations since the cocoa industry became established. However, its modern constitution and mandate reflects the modern trends in the industry especially in the light of Ghana’s socio-economic and political aspirations. Reforms carried out beginning from the 1980s through 1990s to present have restructured COCOBOD significantly. There was the Cocoa Sector Rehabilitation Project funded by the World Bank which included reducing COCOBOD in size by restructuring and re-organising some of the subsidiaries to enhance the share of farmers in the earnings from cocoa exports [6]. Currently, COCOBOD is a relatively slimmer organisation with five main subsidiaries including the Quality Control Company and Cocoa Marketing Company (limited liability companies, which play lead roles in addressing the overall organizational goal of exporting premium and high-quality cocoa). It maintains functionally strong linkages with the critical actors especially its subsidiaries, the licensed buying companies, the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana, the Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus Disease Control Unit (CSSVDCU) and the Seed Production Unit (SPU).

3.3. Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs)

The purchasing of cocoa and its evacuation from the cocoa villages is a daunting task which has implications for the political economy of the crop. The role of the LBCs in tackling this task determines to a large extent the success of reaching the global market with Ghana’s cocoa.

The largest Licensed Buying Company, the Produce Buying Company Ltd. (PBC) used to be a subsidiary of the COCOBOD. It used to enjoy monopoly in the purchasing of all cocoa produced by the farmers. However, the reforms which began in the 1990s came with the deregulation of the cocoa sector and liberalized cocoa purchases. In June 1993, COCOBOD adopted the multiple cocoa purchasing system for internal marketing of the commodity as a means of introducing competition. The legal framework for this was spelt out in the “Regulations and Guidelines for the Privatisation of the Internal Marketing of Cocoa”. The decision to adopt the multiple buying system was really a major step in the reformation of the cocoa sector which was at that time being buffeted by certain challenges making it slide down in competetiveness [7]. The reforms were carried out with one of the goals being the restructuring of the key public institutions in the cocoa sector like COCOBOD and its subsidiaries including PBC. The reforms continued with the enlistment of the PBC on the Ghana Stock Exchange with the public coming in to purchase shares of the company. Currently, the Ghana Government only holds about 37% share of PBC. The Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) holds 38% of the shares and others comprising institutions and individuals hold 25% [8]. Given that SSNIT is a public institution, one may say the ownership of PBC is primarily public. Yet, the 25% completely private ownership is no mean achievement given the historical organization of the company not only as a wholly public institution and a subsidiary of COCOBOD but also the only LBC in the country. Currently, PBC only controls about 33% of cocoa bean purchases in the country and competes against about 26 other LBCs. Yet, it remains a formidable enterprise and was in 2011 adjudged the topmost company in Ghana’s Club 100 which ranks the top 100 companies in the country including the banks and industrial companies whether local or international. Without doubt, the reforms constitute one of the key factors in the revitalization of the cocoa Industry in Ghana. It is one of the experiences in institutional innovation which has re-energized the cocoa industry.

3.4. Cocoa Processing Companies

As far back as the 1960s, there was an effort to process cocoa before export. The West Africa Mills Company (WAMCO) was established by private initiatives to process cocoa beans into cocoa paste, cocoa butter and other products. However, the share of the total processed cocoa in the total cocoa exported was minimal. With one of the major national goals being exporting at least 50% of cocoa as processed, the role of cocoa processing companies has become very important. Currently, there are about five large processing companies operating in the country all at various levels of processing. These are the Cocoa Processing Company (CPC), Barry Callebaut, Afrotropics, Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland (ADM). There is primary processing into the pastes, butter and nibs and there is secondary processing into confectioneries and chocolates. The Cocoa Processing Company (CPC) which used to be a subsidiary of COCOBOD but became privatized with the reformation of the industry currently operates with an expanded installed capacity producing chocolates and cocoa-based sweets and other products for exports and local consumption. Currently, the total installed capacity for processing cocoa is 343,000 metric tons, giving the indication that the country could achieve its medium term policy goal of processing 50% of its cocoa before export. The latest processing company to be established is the ADM company in Kumasi, which has an installed capacity of 30,000 metric tons. The indications are that, good business on the part of the operating processing companies will encourage others to be established. The challenge however is dealing with the threats in the external environment to ensure competitiveness. For example, CPC suffered setbacks in 2011 due to the financial crisis in the European countries where its exports are traded. The average price obtained for cocoa butter during the year was US$3050 per tonne as against an average price of US$5800 per tonne in 2010 [9]. As a result of the marketing challenges and some internal operational difficulties, CPC was only able to process a total of 16952.723 metric tonnes in 2011 as against 21554.960 metric tonnes in 2010 leading to a 21.4% decrease in the processed output of the company [9]. On the whole, marketing is a major challenge for Ghana as it increases its value addition and the overall strategy should be to widen market access to go beyond Europe and America.

The major challenge facing the processing companies suggests that there should be greater linkages among them to enable joint strategizing. Moreover, although the processing companies relate strongly with the COCOBOD and the regulatory bodies such as the Food and Drugs Board and the Ghana Standards Board as they are required to do by the state regulations, their linkage with scientific institutions are not that strong. It is a weakness which does not facilitate innovation in the sector.

3.5. Cocoa Farmers

Where it all begins for the cocoa industry is on the farms of the cocoa farmer living in the semi-deciduous forests spanning six of the ten administrative regions of Ghana and encompassing several of the main ethnic groups of Ghana. Cocoa has enabled these farming households to stay significantly above the national poverty average. Poverty among cocoa farmers has declined significantly and cocoa growth has been more pro-poor than growth in other sectors [10].

There is a Ghana Cocoa, Coffee and Shea Nut Farmers Association (GCCSFA) to which many cocoa farmers belong. However, the challenge for cocoa farmers as it is for most other farmers is that there are several farmer associations which sometimes lead to turf attitudes among them. The cocoa farmers association is still a strong lobby group and could be a means of getting important policy decisions made and adopted by the farmers, in the same way that they could cause a change in government policies once it is found not to be favourable to farmers. Farmers’ representation on the board of the COCOBOD also means that farmers have a voice in the board room discussions of the operations in the cocoa industry.

3.6. International Organisations and Global Companies

The International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) based in London, comprises cocoa producer and cocoa consuming countries. It was established in 1973 to put into effect the first International Cocoa Agreement negotiated in Geneva at the United Nations International Cocoa Conference. There have been follow-up negotiations and conclusions on subsequent agreements. In 2005, the International Cocoa Agreement came into force with the over 80% of exporting countries acceding to the Agreement. ICCO Member countries represent almost 85% of world cocoa production and more than 60% of world cocoa consumption. All Members are represented in the International Cocoa Council, which is the highest governing body of the organization.

The International Cocoa Organisation (ICCO) is a powerful organization bringing the international players together mainly to act to decide on how to structure the global cocoa market for the mutual benefit of all players. In this regard, the cocoa consuming countries of the Western World have a role to play to ensure the balance of power in the organization.

The individual global companies e.g. Cadbury International (now Kraft Food), Mars, Unilever, and several other companies whose food industry depends on raw materials such as cocoa play a role in stimulating cocoa production in the cocoa producing countries such as Ghana. Even though one may always argue that the actions of these trans-national companies are mainly in their organizational interests, what they do also creates the (dis) incentive systems for cocoa production. Currently, Ghana exports its cocoa mainly to Western Europe which accounts for about 67.6%. The main importing countries are The Netherlands (33.8%), UK (12.1%), Belgium (8.9%) and Germany (3.6%). Outside of Europe, Ghana exports to Japan (7.2%) and US (3.3%) mainly [1].

The Alliance of Cocoa Producing Countries (COPAL) which produces about 75% of the world’s cocoa is also one of the key actors in the cocoa industry. The membership includes Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroun, Gabon, Dominican Republic and Malaysia and continues to operate on the Abidjan Charter since its formation in 1962. There have been challenges where members have been unable to take unified positions on the world market. However, by and large, the organization has contributed in ensuring the sustainability of cocoa supply. The Alliance’s main contribution is in the facilitation of exchange of scientific and technical information concerning the production of cocoa in the respective countries.

3.7. Civil Society Organisations

One of the developments in the cocoa industry is the emphasis on social responsibility and human rights. For example the issue of child labour and the demand for the recognition of child rights has become pivots for the increase in the activities of civil society organizations (CSOs) such as International Cocoa Initiative (ICI). Whilst some of the work of the CSOs is desirable, there are cases where issues are not presented or discussed in a manner in which they should be. For example, some of the citations of child labour are misrepresentation of the communal activities typical of the African societies. Children make contributions to the total household income and going to weed or help harvest cocoa pods on cocoa farms do not necessarily mean that children are slaving on cocoa farms. One may agree that all children, irrespective of where they grow up, should be given access to education from primary to tertiary educational institutions especially as Ghana is already implementing the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE). However, the facts of the cultural features of the society need to be presented as is. The Ghana Government in collaboration with ICI has set up the National Programme for the Elimination of Child Labour (NPELC) in cocoa communities. NPELC (under Ministry of Manpower Youth and Employment) with the assistance of COCOBOD has embarked on intensive education using rural FM radio stations to address issues relating to the elimination of child labour in cocoa growing areas of the country.

3.8. Research Institutions

The scientific institution known as Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana (CRIG) has a long history going back to 1938 when the West Africa Cocoa Research Institute (WACRI) was established to investigate disease and pest militating against cocoa production in the West Africa sub-region. WACRI disintegrated with the coming of independence in West Africa and each country sought to have its own research institute to address cocoa production on scientific basis. The institute’s mandate has been expanded to research into other oil seed bearing trees (e.g. shea and cashew) as well as coffee which though minor in their contribution to the total foreign exchange earnings of the country, are important in providing livelyhoods for marginalized segments of the population.

CRIG currently plays the lead role in providing Science and Technology inputs for the cocoa industry. Other institutions like Institute for Statistical and Social Research (ISSER) offer socio-economic research to support the cocoa industry. COCOBOD has a Research Monitoring and Evaluation (RM&E) Department which handles research and development of the board’s programmes and policies to enable it achieve the set objectives.

4. The Trends—Production and Value Addition (Heading 5)

Cocoa production in Ghana has grown through phases of world domination in the 1950s and 1960s when the country produced the largest volume of cocoa, through the 1970s and 1980s when that global domination was abdicated, through a phase of rehabilitation during parts of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Other countries, mainly Malaysia and neighbouring Cote d’Ivoire caught up and overtook Ghana. However, it is not so much of how the country ranks in terms of cocoa production as how the country manages the socio-economic activities surrounding the crop such that, the benefits for the people are maximized.

4.1. Ghana Cocoa Production Trends

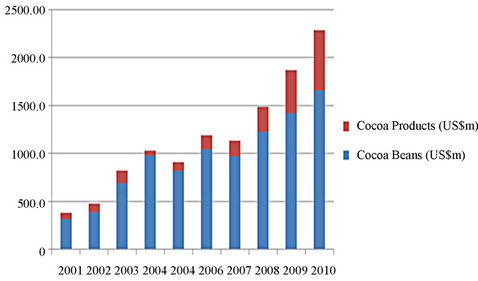

Nevertheless, as Figure 2 illustrates, the total export earnings from cocoa has been increasing since the mid 2000s. Apart from a dip between 2006 and 2007, there has been steady increase from 2007 consistently up to 2010 when the country earned approximately $2.285 billion from total cocoa exports, which contributed 28.9% of the total foreign exchange earnings [1]. It has been the stated policy goal of achieving total cocoa production of one million tons. In 2011, Ghana was said to have achieved that target [11]. What is significant about the trends in cocoa production and exports is the rising component of the value added cocoa.

4.2. Value Addition in the Cocoa Industry

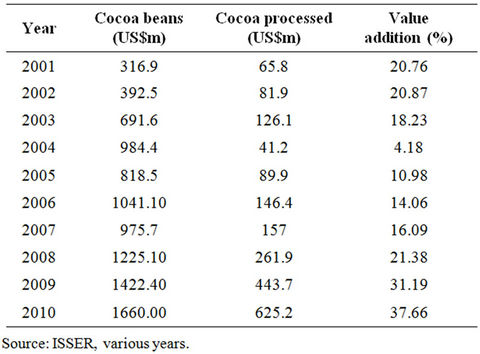

Value addition has been a long-standing national goal in enhancing earnings from the cocoa industry. The current goal is to achieve a 50% processed cocoa as a proportion of the exported. Analysing the component of the processsed cocoa in the exports of cocoa from Ghana gives an indication of the extent to which this goal is being achieved. See Figure 3.

Indeed considering the contributions to the total value of exports of Ghana in the ten-year period between 2000 and 2009, cocoa and its products have contributed 32% of the total as shown in Figure 3. Much of the non-agricultural exports amounting to 62% is coming from mineral exports of which over 90% is from gold. Timber exports contributes 3% as well as non-traditional exports which is a mix of primary agricultural commodities such as horticultural fruits (e.g. pineapples, mangoes and cit-

Figure 2. Cocoa exports—2001-2010.

Figure 3. Foreign exchange earned by agric and non-agric sectors—2000-2009 (US$ million).

rus) and some processed products. There are specific programmes designed to boost the share of the non-traditional exports in particular. However, as may be deduced from Figure 3, the share of the cocoa exports is so dominant of the agricultural component that it may take a long time to reduce its share. More importantly, it shows that there are opportunities for further enhancing foreign exchange earnings. Table 2 gives an illustration of the value addition trend in Ghana.

Figure 2 highlights graphically the increases since 2005 as Figure 3 highlights the importance of the share of cocoa earnings in the national total foreign exchange earnings in recent years. However, the specific issue is how much progress is being made in improving value addition in the cocoa industry.

As shown in Table 2, the significant increase in value addition has occurred in the last three years with the percentage processed cocoa increasing from 16.09% in 2007, to 21.38% in 2008, and to 31.19% in 2009 and then to 37.66% in 2010. Thus there has been consistent increase in the past six years. It appears that this trend will continue as the country strengthens its efforts in attaining the goal of 50% processed cocoa exports. However, an important issue to address is the mix of products in the value added cocoa and the extent to which it enables high premiums to be earned.

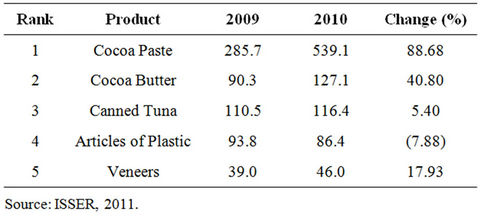

Table 3 shows that the top 5 value added products exported from Ghana comprises cocoa paste and cocoa butter at the very top of the ranking with $539.1 million and $127.1 million in 2010 respectively. The percentage increases of these values compared to the preceding year of 88.68 per cent and 40.80 percent illustrate the growing significance of cocoa manufacturing economic activities in Ghana and the importance of this in the overall manufacturing activities. It is a positive development and the trend is likely to remain positive in the next couple of years. However, cocoa paste and cocoa butter are not in

Table 2. Ghana’s export of cocoa beans and processed cocoa—2001-2010.

Table 3. Top 5 processed/semi-processed products exported, 2009 and 2010 in US$ millions.

the categories of high value-added products such as chocolates, sweets, beverages and cocoa-based cosmetics and the challenge for Ghana remains, how it can break into these high value-added products.

It boils down to the extent of innovation in the cocoa industry and the effectiveness of the engagement and responsiveness of the critical actors in the innovation system to the policy stimuli in the internal and external environment. Innovation must further be enhanced and in fact, catalysed, not only in terms of the high value-added products, but also the diversification of the manufacturing capacities and institutions. Innovation is important in terms of the new processes, products and outcomes in the given socio-economic context. In the last two decades, the cocoa innovation system has shown significant innovations which underscore potentials in deconstructing traditional export commodities and reconstructing into viable diversified products. The innovations may broadly be categorized under institutional innovations and product innovations even though fundamentally they are inter-linked.

4.3. Institutional Innovations

From the Ghanaian experience, a major first step in stimulating innovation is undertaking a comprehensive appraisal of the innovation system and developing a reform package to address gaps and dysfunctions. There were far-reaching reforms in the industry around the organization at the fulcrum of the cocoa industry— COCOBOD. Certainly, the most significant institutional innovation was the deregulation of the internal marketing of cocoa with the promotion of private participation to allow competition. However, it was not only for purposes of competition that the PBC monopoly was dismantled. There was need for efficiency in the entire marketing system. Cocoa purchasing in the villages needed to be conducted in a more businesslike manner with greater supervision and commitment and with brisk evacuation of the bean to the port for export. Private participation was a tool to infuse the needed efficiency into the market.

Currently there are 26 Licensed Buying Companies competing with the PBC in purchasing cocoa from the farmers including international companies such as Armajaro and OLAM Ghana Ltd. Armajaro is a global commodities and financial services business establishment based in the UK and operating in North and South America, Europe, Asia and West Africa. In Ghana it purchases cocoa from farmers as an LBC and also purchases from the Cocoa Marketing Company for export. OLAM Ghana limited is a subsidiary of OLAM International Ltd., which is a Singapore-based global commodity trading company. It was established in 1994 and it has since then grown to become a leading agro-commodity company in Ghana. In the 2003/2004 cocoa season, OLAM Ghana Ltd was the largest private sector licensed buying company (LBC) in the cocoa sector, buying in excess of 75,000 mt. The company is also a leading exporter of sheanut, cashew and coffee.

Some wholly owned Ghanaian companies are also in the business of cocoa purchasing. For example, Kuapa Kokoo Limited (KKL) is a licensed cocoa buying company owned by the Kuapa Kokoo Farmers Union. The KKL is the commercial and trading wing of the Union which operates to generate profits for the farmers in the union to share. Adwumapa Buyers Ltd. is also a limited liability company wholly owned by Ghanaians, which was incorporated in May, 1992. As an LBC, it participates in both the internal and external marketing of cocoa. The participation of Ghanaians in the cocoa business ensures that ownership is not entirely left in the hands of foreigners. Farmer unions also participating in the businesses provide opportunities for the farmers to create more wealth for themselves in the cocoa industry. For example, Kuapa Kokoo Ltd and Akuafo Adamfo Marketing Ltd are making important contributions in granting ready access to market to the cocoa farmer.

Another institutional innovation was the promotion of farmers’ participation in the production of organic and fair-trade cocoa for the export market attracting higher premiums. PBC, Kuapa Kokoo and some other LBCs encourage farmers to go into the promotion of the organic cocoa. Some are also taking responsibility of addressing corporate social responsibility and actively contributing to farmers’ community welfare. These are efforts to develop niche markets and earn more on the exported commodities. However, more can be done to enhance Ghana’s niche market and ensure significant contribution to the total earnings of cocoa exports. The fair trade concept offers good opportunities for creating niches. For example, it is estimated that more than 7.5 million people involved in agricultural sector (farmers, workers and their families) in 59 developing countries stand to benefit from the international fairtrade system. Indeed in 2008, the Fair Trade Foundation UK reported that total sales of fairtrade products for the quarter April to June 2008 grew from an estimated retail value of £113 m to £176 m. The growth encourages efforts to promote the fair trade niche in cocoa exports.

The defunct Cocoa Services Division has been reorganized into two separate units and their mandates expanded. The CSSVD-Control Unit is responsible for the control of the cocoa swollen shoot virus disease of cocoa. The mandate of the Unit has been expanded to include the rehabilitation of old farms (over 30 years) and provision of extension services to farmers under public private partnership (PPP) an innovation in cocoa extension services. With the inception of the PPP five organizations (Armajaro, Kuapa Kookoo Farmers Union, Cadbury Cocoa Partnership, West Africa Fair Fruits and World Cocoa Foundation) have teamed up with the CSSVDCU to provide good extension services to cocoa farmers. The private sector support is in the form of financial assistance (paying the remunerations) for over 70 Extension Agents working with cocoa farmers on various projects set up by these organizations in about 500 cocoa communities. On its part COCOBOD working through CRIG has developed a new curriculum for extension and offers training to these Extension Agents. In addition German Technical Cooperation (GIZ) is supporting the new extension programme by training of cocoa farmers in business skills and providing training manuals, booklets, flyers and posters. The Seed Production Unit is responsible for the multiplication and distribution of improved cocoa and coffee planting materials to farmers.

4.4. Product Innovation

Value addition is a primary concern of existing cocoarelated policies and programmes. There has been the traditional value addition of processing into cocoa paste, butter and confectionery products. However, the drive is to build on these products and ensure Ghana also undertakes the needed secondary and tertiary processing of cocoa for both the local and export markets. One of the most important drivers in this regard is the policy to promote local consumption of cocoa.

Local consumption of cocoa has been stimulated on the promotion of cocoa as a health drink. Indeed it has been scientifically shown that cocoa contains significant levels of antioxidants of flavinols, which are natural compounds found in fruits and vegetables with cardiovascular health benefits. Research work continues on cocoa and its medicinal properties. However, the indications are that, there are active ingredients in cocoa which prevents growth of colon cancer cells and boosts immune systems. The consequences of this have been the development of industries producing powdered cocoa and selling in the shops and supermarkets. Local entrepreneurship is capitalizing on the promotion. The entrepreneur invests in grinding and packaging facilities and produces what basically amounts to cocoa powder without any addition of sugar or milk. Usually, the raw cocoa powder is what is promoted as the health drink.

At CRIG, one of the institutional innovations was the creation of the New Products Unit. CRIG is leading the efforts to add on to the diversification of cocoa products. The new products include cocoa alcoholic beverages, confectioneries, cosmetics and agro-industrial products such as animal feeds. From cocoa sweatings, alcohol can be distilled and researches have determined optimal conditions for alcohol production and the options for Industrial application. Countries such as Brazil have been exporting alcohol from cocoa. It is a difficult change given that for the greater part of a century when cocoa was introduced to Ghana, it was grown as a cash crop and almost entirely exported in bean form. So really the culture surrounding the new products has to be cultivated.

4.5. Key Drivers of Ghanaian Cocoa Superiority

Quality assurance is one thing which Ghana has not compromised on in the cocoa industry. All through the reforms, the government was careful to maintain, if not improve on, the structures for quality assurance. The Quality Control Division (QCD) of the COCOBOD has the mandate to oversee quality assurance from the cocoa villages through the ports. The International Cocoa Standards demand merchantable quality with the cocoa beans being fermented, thoroughly dried, free from contaminants, smoky beans and foreign odour. Ghana cocoa is the standard by which cocoa is measured all over the world. It has a high content of theobromine making the best cocoa for high quality chocolate. QCD addresses its mandate by the inspection of storage sheds and issuing certificates of registration for premises accepted as grading centres or depots. No grading or sealing or storage of any cocoa is allowed anywhere without prior certification by the QCD. The Division has staff stationed in 73 operational districts in all the six cocoa-growing regions of Ghana and they carry out the quality assurance tasks of inspection, sampling, grading and sealing of cocoa before evacuation from the cocoa societies or villages to the take-over points for subsequent shipment or delivery to the local processing factories. Before shipment, the cocoa is sampled again and a “purity certificate” is issued. QCD is also responsible for fumigation and disinfestations.

5. Issues and Challenges in Ghana’s Cocoa Industry

Having discussed the trends in the cocoa innovations system, there are salient issues which one may discuss to put into better perspective the options for policy and strategies vital for the achievement of goals. In the main, these issues relate to the experiences of the policy cycles (from policy formulation to policy evaluation), strategies for attracting investment and capacity development and the application of Science and Technology.

5.1. Policy Formulation, Implementation, Monitoring, Evaluation and Coordination

The cocoa sector is one of the few with strong policy management effectiveness. There are clearly spelt out policies and regulations to guide actor roles and actions right from planting the seedlings through the tedious chores of cultivating the crop to harvesting and going into internal marketing and then through the ports to the external buyers. There are policy measures such as increasing the producer prices of cocoa with a national commitment of paying 70% of net Free on Board (FOB) to farmers and still paying bonuses to cocoa farmers at the end of the cocoa season, disease and pest control programmes and deliberate promotion of agronomic practices to increase yield per acre and thereby increase the total production of cocoa should the same total farmland be all that is available. There is the promotion of application of fertilizers on the cocoa farms under the Cocoa Hi-Technology Programme, which used not to be the case previously. Apparently, the effectiveness of the policy management process is contributing to the success in the cocoa Industry. Yet there are areas in which there can be further improvement.

One major area needing strong policy intervention is in the area promoting local consumption of cocoa. For example there is the Ghana School Feeding Programme (GSFP) which was initiated with the main objective of improving on the nutrition of school children. There is no input at all from the cocoa sector. But menus can be designed such that in all the public schools in Ghana, the GSFP will serve as a means of further realizing the goals and objectives of promoting the local consumption of cocoa. Cocoa drinks could be served regularly as snacks or along with the lunches served. Chocolates could also be distributed regularly e.g. every Friday or perhaps twice a week to the school children. This will definitely create a huge market for the processors. More importantly, getting school children to appreciate cocoa products enables them to grow with the habit and entrench cocoa consumption in the coming generations of Ghanaians.

Beyond the specific policy issues, there are the more generic policy issues relating to the overall socio-economic policy framework which supports and nurtures businesses and strengthens the cocoa value chain in a manner that enhances competitiveness [12]. It is generally known that African countries like Ghana have a high cost investment environment that depresses private sector development and growth [13]. Infrastructural and utility services, finance and capital, land, labour, governance and judicial systems are all examples of the components of the environment that needs significant improvement to make the investment climate more conducive to private sector growth. Cocoa businesses are likely to show more significant growth when the core elements of the country’s investment climate is improved.

5.2. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

One of the important programmes going on in the cocoa sector is the formation of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in cocoa extension to boast cocoa production. Specifically, there is the Cadbury Cocoa Partnership which links the COCOBOD and Cadbury International to implement extension services in selected cocoa-produing communities to improve cocoa production.

The Cadbury Cocoa Partnership was launched in 2008 as Cadbury joined the Business Call to Action to secure the economic, social and environmental sustainability of cocoa farmers and their communities in Ghana, India, Indonesia and the Caribbean. The Cadbury Cocoa Partnership, a £45 million ($73 million) commitment, supports sustainable cocoa farming and seeks to improve the lives and incomes of the farmers who supply Cadbury with cocoa beans. In Ghana about $4.6 million had been spent on the Partnership as of February 2010. The main goals of the Partnership are to:

• Promote sustainable livelihoods for one million cocoa farmers;

• Increase crop yields for farmers participating in the program 20 percent by 2012 and 100 percent by 2018;

• Create new sources of income in 100 cocoa-farming communities in Ghana;

• Address key issues affecting the cocoa sector, including child labor, health, gender diversity, and environmental sustainability.

Apparently, the partnership has scored such a high success that other cocoa companies operating in the country has signed onto the partnership with COCOBOD including Kuapa Kokoo and Armajaro. It is still not easy to project how far the partnership will go. But it is likely to gather momentum and envelope more cocoa companies and definitely more cocoa communities. More importantly, this particular model is signaling a new and evolving framework for public institutions to engage private sector actors to promote development while doing business.

5.3. The Importance of Research and Development

CRIG has been tasked to undertake agronomic research into problems relating to disease and pest, production of cocoa and other indigenous tree species which produce fat similar to cocoa butter. Provide information and advice on matters relating to production of cocoa and other related mandated crops.

Indeed at the heart of the success of Ghana’s cocoa is the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana. The Institute is manned by 35 professional staff, 175 technical staff and some other supporting staff making it one of the largest research institutes in the country. Although CRIG is generally known for researching and developing improved varieties of cocoa for farmers and more productive agronomic practices, it also conducts research on cocoa products. Some of the innovations coming from CRIG include the production of cocoa butter soap, cocoa jam, cocoa vinegar, brandy, body pomade and other cosmetics. Some of these products have actually been adopted by some entrepreneurs for commercial production. For example, Kasapreko Co. Ltd., one of the leading local companies producing alcoholic drinks, is making good business bottling cocoa brandy for the local and export market.

However there are constraints in promoting the linkage between the R&D system and the industrial sector. Some of the constraints are generic requiring broad policy interventions to address dysfunctions. These include the investment policies to attract the needed capital to commercialize research innovations such as what is at CRIG. Specific policy actions are necessary targeting innovations in the cocoa sector and concretely linking into existing national programmes. For example, there is the Ghana School Feeding Programme, which provides feeding for primary schools in low-income communities all over the country. The challenge of feeding Ghana’s population nutritiously, is a challenge that faces all of Africa [14]. Cocoa beverages could be included in the programme and hence upscale the market for cocoa products. Really there is no gainsaying the fact that there are opportunities for driving innovations in the sector and through synergistic policy actions.

5.4. Global Threats

There are technological developments that continue to justify sustained R&D and innovation in Ghana and other producer countries. The development of Cocoa Butter Equivalents (CBE) from other sources than cocoa e.g. palm oil, shea and mango kernels, is threatening to reduce the quantities of cocoa used in chocolates and other products [15]. The EU has approved up to 5% use of CBE in chocolates and this is estimated to reduce total demand by some 200,000 tons. The 13-member Cocoa Producers Alliance has opposed the approval of CBEs [16]. However, the opposition has been sidelined and the approval came into law in 2000. The option left for cocoa producing countries is to increase production to make it less cost-effective for chocolate producers to use CBEs. This implies greater application of science and technology in the production of the cocoa bean, a more diversified use of cocoa to increase demand and a vigorous increase in home consumption of cocoa.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

In considering the cocoa innovation system, the effectiveness of the roles of the critical actors determines the progress made in achieving set goals and objectives of the cocoa industry. Innovation crystallizes from the interactions and co-workings of the critical actors and the application of new knowledge.

The role of government is central to the cocoa industry in Ghana. Through the key public institutions such as COCOBOD, a fulcrum has been provided for the cocoa value chain activities. In the last two decades, there have been significant innovations of institutional and product dimensions. The reforms of the 1990s and 2000s have led to more efficient public institutions and opened the way for an enhanced private sector participation in the cocoa industry. The PBC which used to enjoy a monopoly is currently in competition with about 26 licensed buying companies and the landscape of internal marketing of cocoa has changed dramatically. Other market stimuli have surfaced including the fair-trade concept, social responsibility and human (child) rights issues. Such external market stimuli create opportunities for further innovation.

However, innovation has to be strategically pursued and in a synergistic manner. The role of CRIG in ensuring scientific approach to product innovation in the various components of the value chain—production and processing mainly—is exemplary. Yet, the application of Science and Technology alone is not sufficient. There are socio-economic strategies such as specific policy actions to improve investment climate and develop niches. There must be incentive systems to encourage the private sector to engage the public sector in partnership. Ghana cocoa has potential to grow but the potential needs a strategic push.

REFERENCES

- ISSER, “The State of the Ghanaian Economy in 2010,” Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research, University of Ghana, Legon, 2011.

- B.-A. Lundvall, “National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning,” Pinter, London, 1992.

- L. K. Mytelka, “Local Systems of Innovation in a Globalised World Economy,” Industry and Innovation, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2000, pp. 15-32. doi:10.1080/713670244

- R. R. Nelson, “National Systems of Innovation: A Comparative Study,” Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1993.

- B. Oyelaran-Oyeyinka and K. Lal, “SMEs and New Technologies Learning E-Business and Development,” Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2006. doi:10.1057/9780230625457

- A. K. Fosu and E. Aryeetey, “Ghana’s Post-Independence Economic Growth: 1960-2000,” In: E. Aryeetey and R. Kanbur, Eds., The Economy of Ghana—Analytical Perspectives on Stability, Growth and Poverty, James Currey, Suffolk, 2008.

- G. O. Essegbey, “Chapter Two—Ghana: Cassava, Cocoa and Poultry,” In: K. Larsen, R. Kim and F. Theus, Eds., Agribusiness and Innovation Systems in Africa, World Bank, Washington, 2009.

- PBC, “Produce Buying Company Ltd Annual Report 2009/2010,” Produce Buying Company Ltd., Accra, 2010.

- CPC, “CPC Annual Report 2011,” Cocoa Processing Company Limited (CPC), Accra, 2011.

- C. Breisinger, X. S. Diao, S. Kolavalli and J. Thurlow, “The Role of Cocoa in Ghana Future Development,” Ghana Strategy Support Program (GSSP), Washington, 2008.

- RM&E, “COCOBOD Annual Report, Research,” Monitoring & Evaluation of COCOBOD, Accra, 2011.

- UNIDO, “Agro-Value Chain Analysis and Development: The UNIDO Approach,” Vienna, 2009.

- B. Eifert and V. Ramachandran, “Competitiveness and Private Sector Development in Africa—Cross-Country Evidence from the World Bank’s Investment Climate Data,” Asia-Africa Trade and Investment Conference (AATIC), Tokyo, 2004.

- C. Juma, “The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa,” Oxford University Press, New York, 2011.

- M. Buchgraber and E. Anklam, “Validation of a Method for the Quantification of Cocoa Butter Equivalents in Cocoa Butter and Plain Chocolate—Report on the Validation Study,” European Commission Joint Research Centre, Brussels, 2003.

- European Parliament, “Directive 2000/36/EC of the European Parliament and the Council June 2000 Relating to Cocoa and chocolate products intended for human consumption,” OJ L197, 2000, pp. 19-25.

NOTES

1Exchange rate is US$1 = 1.5 Ghana cedis.