Natural Resources

Vol.3 No.4(2012), Article ID:26292,8 pages DOI:10.4236/nr.2012.34031

To What Extent Are Cities Influenced by Rural Urban Relationships in Africa

![]()

Institute for Systems Science, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa.

Email: tsimelane@ai.org.za

Received August 7th, 2012; revised October 17th, 2012; accepted October 28th, 2012

Keywords: Urban Dynamics; Urban Settlement; City Centers; Rural-Urban Relationship

ABSTRACT

If rural-urban relationship is treated as an open and unregulated process, cities serve as a sink for rural population, meaning that higher proportions of rural people migrate from rural areas to stay permanently in the cities. This process, which is commonly referred to as rural urban migration can be more evident if the urban system is maintained as an open system. This holds key to interpreting how cities attract and retain their populations, a process that is critical to understand the causes of deterioration of most cities in developing countries that still draw much of their population inputs from rural areas, as it is the case with Africa. Deducing from South African experience, if policies that regulate movement of people between rural areas and cities are politically inclined they tend to give a particular character to the evolution and development of cities. This has been found to be true for two sets of policies implemented in South Africa. Ones that were implemented during Apartheid, while they encouraged the migration of unskilled laborers from rural to urban areas, failed to promote settlement and adaptation of African communities in the cities and this led to an upsurge of informal settlements around many cities of South Africa. One that have been implemented since the advent of Democracy, due to their relaxed nature have led to an influx of people of African descent into the city centers and the effect of this has been the deterioration of these areas. With these findings this study cautions that urban system needs to be treated as open, that is, be allowed to regulate itself through economic success and failures of people who aspire to live in urban areas by choosing to settle in the cities.

1. Introduction

Economic disparities are a main differentiator between rural and urban areas [1,2]. On determining the extent of relationship between urban and rural areas, economic disparities are a cause for people to migrate from rural to urban areas. This takes place in the form of people migrating from less economically active (rural) areas to more economically active urban areas [2]. While this seems to represent a natural search for population equilibrium between rural and urban areas, migration of people from rural to urban areas widens the economic gap between the two areas [3]. For rural areas it entails the departure of resourceful, skilled and educated people [4]. For urban areas it entails an increase in the population densities and the subsequent demand for resources and the emergence of complex systems. These influences of rural areas on urban areas have direct impacts on urban areas, which expresses itself in the form of urban decay, environmental degradation, overpopulation and the development of anti-social behaviours such as crime [3].

Other than economic disparities, movement of people between rural to urban areas is further encouraged by 1) incentives that are provided by urban areas; 2) earning differentials that exist between rural and urban areas; and 3) the hope of securing a job at the urban destination [1,2]. The hidden reality linked to these expectations, which many rural migrants ignore, is that the prospect of getting a job in the urban area may not materialize [1], with limited skills they find it difficult to be absorbed by the urban economy. This leads to perpetual urban poverty [1,5] and unemployment that result from the oversupply of skills that do not match the available employment opportunities.

While it can be noted that migration (i.e. movement of people from one place to the other in search of better conditions) is an independent process that occurs naturally [5]. Within the human species it is a process that is constantly regulated through certain policies. In this regard, South Africa provides an interesting case study. After the discovery of diamonds, gold and other minerals, the demand for labour in urban areas of South Africa became insatiable [6]. This defined the relationship between rural and urban areas, where rural areas served as sources of cheap Black labour [7]. To encourage the migration of Black labourers from rural to urban areas certain policies were devised. These heightened the miation of black labourers from rural to urban areas. In return, they destroyed the economies of rural areas [6]. First to introduce these policies was Cecil John Rhodes. Through the Glen Grey Act of 1894, he encouraged Black urbanization by creating a division between rural blacks who were involved in full-time farming and those that were landless who would then migrate to urban areas to seek fortunes in the cities [6].

Similar, but altered initiatives includes the Smit Committee of 1942 [6], the Social and Economic Planning Council of 1946 and the Fagan commission, which recommended that the movement of Black people from rural to urban areas had economic benefits and should be maintained as a system that promote the supply of unskilled labourers to urban economies [6]. This was rejected in 1948 when the National Party came to power, on political ground that racial segregation in South Africa should be maintained in all spheres of life and permanent residence in the cities kept as an exclusive right for Whites [6]. Through this, policies like Group Areas Act, which entailed the forceful removal of Blacks from urban areas and other restrictive policies like Influx Control were implemented. All prohibited Blacks from settling permanently in the urban areas, especially the cities.

With the acquisition of Democracy in 1994, all restrictive policies were removed and this had since seen the emergence of new patterns of urban settlement, development and transformation where settlement of Blacks to urban areas, especially the city centres has reached the uncontrollable levels. Today almost all city centres of South Africa are populated by Black communities. The concern around this trend is that people are abandoning rural areas in favour of city centres.

A notable characteristic that has emerged is that populations that have settled in the city centres are not only composed of people who come from rural areas of South Africa, but include people who come from other cities in Africa [7]. With this emerging character of urban transformation and dynamics in South Africa it becomes imperative to interpret changes that are taking place in the city centres of South Africa in line with the current policies that regulate urban development and settlement. This will help to understand the sources of attraction of the city centres and their future outlook under various political scenarios. It will aid the design of policies that will not only seek to reduce rural urban migration but will ensure that urban influx is regulated and managed within the political position and transformation of a country.

In general, what has happened in South Africa since the removal of restrictive policies demonstrates that politically aligned rural urban policies are capable of defining the nature of the relationships that may exist between rural and urban areas. This derives from observation that policies that were implemented in South Africa during apartheid, due to their restrictive nature led to an upspring of informal settlements around cities and those that had been implemented since the advent of Democracy, due to their relaxed nature have led to population explosion in the city centres. All these alter the demand and use of resources needed for urban adaptation.

2. Defining the Basis of Rural Urban Relationship

The term rural urban relationship has a long history. It was coined to mark a departure from the traditional view of rural-urban dichotomy which was particularly prevalent at the turn of the 19th Century [8]. This was a time when many European countries were experiencing a rapid transformation from largely rural to industrial economies [8] and thus rural urban relationship is defined through people migrating from rural to urban areas in search for opportunities in urban areas. However, urbanization process is an important element of human development in general [9] and thus rural urban linkages need to be understood and addressed in the context of globalisation which highlight these linkages in terms for worldwide systems of production and industrialisation [8].

Urbanization and industrialization are thus twin pillars of the processes that define the relationship that exist between rural and urban areas [10]. As a response to the pull effect of industrialisation, rural population leave rural areas hoping to get employment and improve their lives in urban areas.

Finding that employment opportunities are limited in urban areas, migrants resort to informal sector and participate in it as a coping mechanism. As a first step towards adapting to urban areas they use overpopulated areas to meet their basic need of accommodation. Once this has been met, they then broaden their scope of needs to other issues. This represents a simplified process of rural migrants’ adaptation in urban areas. However, the main challenge is to define how these processes shape cities so as to successfully interpret the influences of rural areas on urban areas and how these differ between instrialised and developing countries.

In doing this, this article adopted the concept of emergence, in an open system i.e. how, through a series of processes at one level, new characteristic at other levels are generated [11]. This notion has been used to interpret how one factor at a lower and initial level of a system interacts to produce a character at a secondary level, which ultimately produces some characteristics of the system. This approach has been used to define changes that had occurred in the city centres of South Africa that have occurred as a response to the influx of people to city centres from rural areas. Arguments raised seek to contribute to the understanding of urban transformation and dynamics in Africa.

3. How Changes in Rural Economies of South Africa Affected Urban Areas

The cycle of rural-urban link and its effects on South Africa’s urban social system can be best explained by tracking changing demands of labor that took place in various industrial sectors since 1960. Until the late 1960’s or early 1970’s rural populations of South Africa were divided into communities of what were referred to as “Red people” i.e. those who tried to defend African identity and culture and “Schooled people” i.e. those that aspired to white civilization [6].

Economically rural black populations were stable and extensively engaged in agriculture and pastoralism. Cattle dominated their wealth. This was supported by the knowledge of agricultural production that was well entrenched within the rural communities [6]. Entrepreneurial skills that were based on traditional knowledge systems afforded them advantages to compete successfully in the markets. The manipulation of the agricultural economy and the exclusion of rural farmers from competing fairly with white farmers, through the creation of double economies, restricted the participation of rural farmers in the economy and this ultimately destroyed rural production.

This triggered the migration of people from rural to urban areas in search of employment. The system under which this form of migration took place saw a series of complexities emerging, first being the increase of food insecurity both in rural and urban areas. At a national level, a key feature was the creation of an enormous amount of non-rural settlements that were closer to urban areas, which were mostly communal and lacked formal governing structures. This form of settlement entrenched circular migration between rural and urban areas. It further deepened a pattern of extremely distinct settlements that had highly specific challenges. These included:

• settlements that were surviving on the mercy of apartheid;

• settlements that were associated with new forms of economic activity, such as self governing states;

• those where residential hostels were built as dormitories to house migrant laborers;

• settlements that were non-reserve urban areas that often re-housed those forcibly removed from old residential areas in towns;

• the capitals of self-governing territories whose existence was largely subsidized by Apartheid government.

These types of settlements offered limited economic opportunities and relationship between rural and urban areas. They attracted increasing developments of at least three types. These are 1) formal serviced housing development; 2) informal not serviced settlements close to cities; and 3) high density not serviced settlements around cities. This portrays how cities can directly be influenced by rural areas.

4. The Extent of Rural Influence on Cities: The Experience of South Africa

4.1. Methodology

The changes that have emerged in the cities of South Africa somehow reflect successes and failures of the policies that have been implemented. The impacts of these have unfortunately been overshadowed by the fact that the foot prints of the past policies that were implemented during Apartheid still persist [12]. Thus, emerging characters of city transformation that are currently witnessed in South Africa demand that accurate and effective techniques such as system dynamics analysis are applied to develop an understanding of the root causes of city transformations.

System dynamics is able to magnify relations and interdependencies among the elements of the system. The technique was developed in the mid-1950s by Professor Jay W. Forrester of Massachusetts Institute of Technology [13]. From early 1950s to late 1960s it was exclusively applied to corporate and managerial challenges [14,15]. The encounter of Professor Forrester with John Collins led to the expansion of the application of system dynamics to interpreting urban problems [13,16-18].

Through this extension of the application of system dynamics to other areas, Jay Forrester produced his classical work on urban dynamics, which was later followed by systems simulations for urban planning and analysis [19]. Since then, the application of system dynamics has been extended to various areas such as system analysis [20-22], planning [22-24] and decision making [25].

4.2. Data Collection Method

Non experimental, quantitative and inferential methods were used to collect data presented in this study. Data were collected using questionnaires. This method was favored over others in that it allows faster and more efficient collection of data. The survey was conducted among the city centers of Pretoria, Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town.

During each survey, the following set of data was collected:

• Information about the origin of a person interviewed;

• Income level of respondent;

• Reasons for moving into city centre;

• Willingness to go back to the area of origin;

• The challenges a person experiences through residing in the city centre;

• The different types of food a person can afford to buy;

• Whether a person was living in a family, commune or singly in his or her place of residence and

• Whether a person was renting or owning a property in which she or he was living.

For each city a target of 200 (maximum) people were chosen as a representative sample to be interviewed in each of the affected areas of the chosen cities. The age of the target people ranged between 20 and 50 years. Interviews took place on an informal basis with the interviewee, and were based on informal discussions that were guided by the structured questionnaire.

Within each city, the study focused on areas identified as densely populated and deteriorating. Such areas were Central in Port Elizabeth, Yeouville in Johannesburg, Sunnyside in Pretoria and Central Districts of Durban and CapeTown.

A consideration that the urban system constitutes complex sub-systems with many dynamically changing parameters increased the significance of this study within the field of urban dynamics. Data collected and interpreted thus intends to lay a foundation for future monitoring of changes that are likely to take place in the studied cities.

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Population Structure

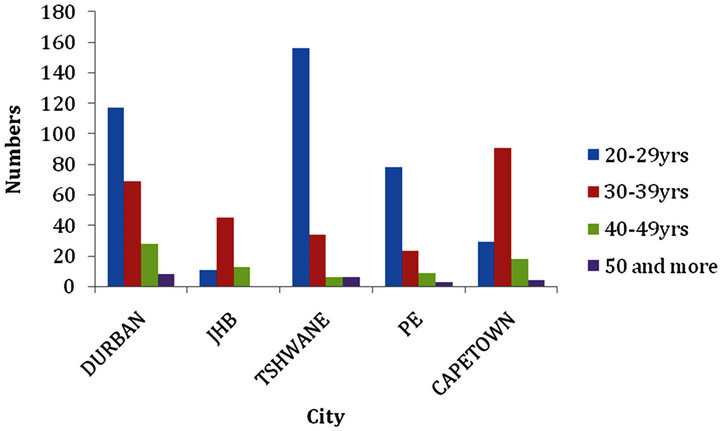

The city centre populations were found to have been transformed such that African populations are now a majority. These are composed of persons with ages that range between 20 and 39 years (Figure 1). Most of them are either working in government departments, studying, looking for a job or are trying to set up a small business. A proportion that seeks to set up a small business is in actual fact attempting to participate in the informal economy of the city centre as a complementary coping mechanism.

The age distribution (Figure 1), reflected some similarities between the cities, where there was a high peak at age category 1 - 2 (i.e. 20 - 29 yrs and 30 - 39 yrs) for Port Elizabeth, Durban and Pretoria, and high peak at 2 - 3 (i.e. 40 - 49 and 50 and above) for Johannesburg and Cape town.

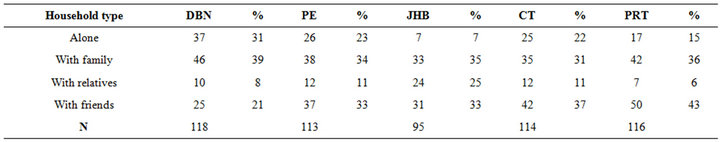

Two classes of household were found to exit in the studied city centres. These were classified as city centre residents and non city centre residents. City centre residents were defined as those that own a house or a flat in the city centre and non-residents were those who prefer to rent the property in which they live. This classification was based on the assumption that those who have decided to invest in a property intend to stay permanently in the city centre. Household composition was such that most people live as family (Table 1).

4.3.2. Changes that have Emerged

In general a series of changes that touches upon all aspects of social life, business and city transformation have emerged in all studied cities. These can better be presented through a system dynamics model provided below (Figure 2). The model shows that studied cities draw their populations from all nine provinces of South Africa (i.e. they provinces serve as net suppliers of people to cities). Some come from other parts of Africa. These have migrated to major cities of South Africa, reasons provided being looking for employment, to study, visiting a relative or attempting to start a business.

As might be expected future growth trends of populations in the cities will be largely influenced by birth and migration rates (these can be regarded to be future enablers of population growth). However, overall population

Figure 1. Age structures of cities that has emerged since the implementation of the new policies (JHB = Johannesburg, PE = Port Elizabeth).

Table 1. Type of house-hold where city centre residents stay.

Figure 2. A system dynamics model showing drivers of change in the city centers of South Africa.

growth rates will be kept within the carrying capacities of the cities by available employment opportunities, deaths and emigration rates (these can be regarded as constraints).

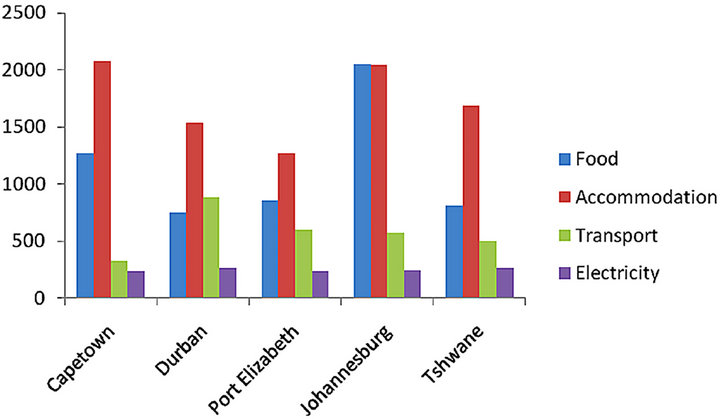

The noticeable effect that has been brought by changes that has taken place in South African cities is the shortage of accommodation (Figure 3). In all studied cities, residents were found to spend much of their income on accommodation. This was of no surprise as there is a direct correlation between population growth and the shortage of resources such as accommodation, space and other amenities.

To give an overview of the seriousness of the shortage of accommodation in the cities of South Africa, to date the Department of Housing has provided more than 2.4 million houses. The latest indication is that the housing backlog stands at 2.2 million, mostly to urban dwellers. The inability of the government to meet the demand is due to various reasons. These have been cited as a lack of access to land for housing development, lack of access to housing finance, sub-standard work, corruption, the normalization of the housing market to create a single residential property market and the exponential increase of building costs due to the increased demand for building materials.

In addition Goebel (2007) [26] has listed following alternative views:

• The low-cost housing program is continuing to place poor and low-income blacks in low serviced townships that are far from jobs and services;

• Low quality houses and infrastructure are rapidly deteriorating and require constant maintenance;

• The dynamics of poverty is inadequately dealt with by a dominant model of free-hold tenure, as several poor people would be better served by rental accommodation;

• People prefer larger houses than the small ones currently provided by the government.

A combination of these challenges together with a mix of others have made people sell or rent out their houses and move back to informal settlements that are closer to cities. This has created a cycle of the demand for houses and perpetual poverty in urban areas of South Africa.

5. Discussion

While it can be emphasized that economic disparities between rural and urban areas are a main trigger of movement of people between rural and the cities, it can be concluded from this study that political reforms have a

Figure 3. Expenditures patterns of five studied cities.

direct influence on this process. This has been confirmed as true for South Africa where political transformation from Apartheid to Democracy has triggered series of changes that have emanated in city centers. What can be deduced from this is that policies that seek to modify urban rural relationship may exert negative effects on cities. In most cases these fall short of having the desired effects [27].

Considering that city centre populations of South Africa are increasingly becoming more heterogeneously due to the fact that they are composed of people from various parts of Africa, it becomes obvious that within the city centres of South Africa new characteristics are emerging. These are likely to be reflected in all cities of South Africa very soon. How this is going to affect the attractiveness of these cities needs to be analysed through reliable tools like system dynamics models. System dynamics regards human beings as central actors to the system [28]. It considers a human being as able to influence the system directly. In doing so human beings adapt and acquire the highest levels of development [29].

If this takes place at a group level it reflects the value system of the society or a group. This emerges from the natural ability of humans to modify their system, which is referred to as adaptation or re-creation. This enables the system to change, maintain, adapt and reproduce itself [30].

Using this to interpret the effects of rural areas in cities, it can be said that changes (either positive or negative) that are observed in a transforming city may represent some form of adaptation and system modification. With the signs of urban poverty already emerging in the city centres of South Africa, the important challenge facing South Africa is now to break the cycle of poverty both in cities and rural areas.

Statistical indications suggest that approximately 40% of South Africans are trapped in poverty—with 15% being in a desperate struggle to survive [31]. This means that approximately 18 million out of total population of South Africa can be regarded as have not yet experienced the benefits of democracy. This can be the reason behind the nationwide protests currently taking place in South Africa.

In addition statistical estimates suggest that at least 15 per cent of all households in South Africa suffer from chronic as opposed to transitory poverty: that is, they remain in poverty when measured over time and this poverty has been transferred to cities.

On a limited scale it can be noted that South Africa’s political transformation has resulted in an increase in rural incomes.

This derives from the fact that African rural pensioners now receive earnings equal to those received by whites in urban areas. This represents an increase in the disposable income of the elderly in rural areas who constitute a larger portion of the rural population. While this sounds fair the reality is that social grants are not the best way of addressing poverty, policies that will promote rural agricultural development and convert rural areas to be suppliers of food to cities are a desirable solution that promote the establishment of a balanced relationship between rural and urban areas.

6. Conclusion

This study has shown that among developing countries, rural areas are the main source of city migrants. While this character has long diminished among the developed world [8], in Africa this still defines the relationship that exist between rural and urban areas. As most migrants move to cities in search for employment and study opportunities, failure of the cities to absorb such people through economic opportunities means that cities end up having an oversupply of skills that cannot be absorbed by the economy of the city. As a coping mechanism, these people develop the informal sector of the cities. The overall effect of this is the increase in the population of informal traders. This process explains why most cities in Africa have high proportions of informal traders, a character that has made most cities in Africa to lose their attractiveness. For South Africa, why relationship between rural and urban areas were primarily based on policies that seek to increase the movement of unskilled labourers from rural to urban areas, the fact that these have since been removed means that South African cities are on the footsteps of other African cities. This requires policy interventions that will reverse those processes that indicate that these cities are on deteriorating trends.

7. Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF). Guidance on methodology, analysis and review was provided by Profs K. Duffy and B. Pierce of Durban University of Technology. Their inputs are highly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- J. R. Harris and M. P. Todaro, “Migration, Unemployment and Development: A Two Sector Analysis,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 60, No. 1, 1970, pp. 126- 142.

- J. J. Silveira, A. L. Espindola and T. J. Penna, “An Agent Based Model to Rural-Urban Migration Analysis,” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, Vol. 364, 2006, pp. 445-456.

- A. Bigsten, “Adaptation and Distress in the Urban Economy: A Study of Kampala Households,” World Development, Vol. 20, No. 10, 1992, pp. 1423-1441. Hdoi:10.1016/0305-750X(92)90064-3

- A. Portes, “Migration and Underdevelopment,” Politics Society, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1978, pp. 1-48. Hdoi:10.1177/003232927800800101

- G. S. Fields, “Rural-Urban Migration, Urban Unemployment and Underdevelopment and Job-Search Activity in LOCs,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1975, pp. 165-187. Hdoi:10.1016/0304-3878(75)90014-0

- P. Mayer, “Black Villagers in an Industrial Society: Anthropological Perspective on Labour Migration in South Africa,” Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1980.

- P. Bond, “Cities of Gold, Township of Coal: Essays on South Africa’s New Urban Crisis,” Africa World Press, Trenton, 2000.

- S. Davoudi and D. Stead, “Urban-Rural Relationships: An Introduction and Brief History,” Built Environment, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2002, pp. 269-277.

- J. Azam and F. Gubert, “Migrant’s Remittances and the Household in Africa: A Review of Evidence,” African Journal of Economics, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2006, pp. 426-462. Hdoi:10.1093/jae/ejl030

- E. B. Lucas, “Migration and Economic Development in Africa: A Review of Evidence,” African Journal of Economics, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2006, pp. 337-395. Hdoi:10.1093/jafeco/ejl032

- J. Doyle and D. Ford, “Mental Models Concept for System Dynamics Research,” System Dynamics Review, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1999, pp. 411-415. Hdoi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1727(199924)15:4<411::AID-SDR181>3.0.CO;2-R

- P. Checkland, “Systems Thinking, Systems Practice,” John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, 1981.

- S. Van der Berg, “Apartheid’s Enduring Legacy: Inequalities in Education-Super-1,” Journal of African Economics, Vol. 16, No. 5, 2007, pp. 849-880. Hdoi:10.1093/jae/ejm017

- J. W. Forrester, “Industrial Dynamics,” The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1961.

- J. D. Sterman, “Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modelling for Complex World,” Higher Education, McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- J. W. Forrester, “World Dynamics,” Wright-Allen Press, Cambridge, 1971.

- A. Ford and H. Flynn, “Statistical Screening of System Dynamics Models,” System Dynamics Review, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2004, pp. 273-303. Hdoi:10.1002/sdr.322

- W. D. Nordhaus, “World Dynamics: Measurement without Data,” Economic Journal, Vol. 83, No. 332, 1973, pp. 1156- 1183. Hdoi:10.2307/2230846

- L. Alfeld, “Urban Dyanamics—The Fifty Years,” System Dynamics Review, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1995, pp. 199-217. H doi:10.1002/sdr.4260110303

- J. Forrester, “Industrial Dynamics: A Major Breakthrough for Decision Makers,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 36, No. 4, 1958, pp. 37-66.

- G. P. Richardson, “What Are We Publishing? A Review from Editor’s Desk,” System Dynamics Review, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1991, pp. 61-67. Hdoi:10.1002/sdr.4260070105

- G. J. Scholl, “Benchmarking the System Dynamics,” System Dynamics Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1995, pp. 139-155. Hdoi:10.1002/sdr.4260110204

- R. Espejo, “What Is Systemic Thinking?” System Dynamics Review, Vol. 10, No. 2-3, 1994, pp. 199-212. Hdoi:10.1002/sdr.4260100208

- C. Mitchell, “Situational Analysis and Network Analysis,” Connections, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1994, pp. 16-23.

- L. C. Freeman, “Computer Programs in Social Network Analysis,” Connections, Vol. 11, 1988, pp. 26-31.

- A. Goebel, “Sustainable Urban Development? Low Cost Housing Challenges in South Africa,” Habitat International, Pretoria, 2007.

- E. F. Wolstenholme, “System Enquiry: A System Dynamics Approach,” John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, 1990.

- A. W. Wolfe, “The Rise of Network Thinking in Anthropology,” Social Networks, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1978, pp. 53-64. Hdoi:10.1016/0378-8733(78)90012-6

- P. Checkland, “Systems Thinking, Systems Practice,” John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, 2008.

- C. Bey and R. Isenmann, “Human Systems in Terms of Natural Systems? Employing Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics for Evaluating Industrial Ecology’s Ecosystem Metaphor,” International Journal of Sustainable Development, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2005, pp. 189-206. Hdoi:10.1504/IJSD.2005.008890

- F. Capra, “The Hidden Connotations,” Flamingo, London. 1996.