International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.2 No.2(2011), Article ID:5099,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2011.22020

An Epidemiologic Study of Depressive Symptoms among Cardiometabolic Department Patients in México

—Depression in Cardiometabolic Patients

![]()

1Clínica Cardiometabólica, Escuela de Enfermería y Salud Pública, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, México; 2División de Estudios de Postgrado, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas y Biológicas “Dr. Ignacio Chávez”, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, México.

Email: jcmavocat@yahoo.com.mx

Received December 28th, 2010; revised April 6th, 2011; accepted April 19th, 2011.

Keywords: Cardiometabolic, Depression, Prevalence

ABSTRACT

Background: This study estimated the prevalence of depressive symptoms among cardiometabolic department patients in México. Methods: To identify patients with depressive symptoms, we used the Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI). We analyzed data from consecutive adult patients who attended during a year to a Cardiometabolic Department in México and described the demographic, metabolic and vascular status differences between depressive and non-depressive patients. The estimates are based on a total of 180 patients aged 22 to 83 years. Results: There was a depressive symptoms prevalence rate of 60.5%. Compared with non-depressive patients, depressive patients were more likely to be obese, and to have dysglucemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypoalphalipoproteinemia, microalbuminuria, high uric acid levels, carotid atherosclerosis, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Conclusions: Our data suggest that prevalence of depression is elevated among cardiometabolic patients in México. Depression probably plays a role in cardiometabolic physiopathogenic, and must be intentionally assessed in cardiometabolic patients in order to treat it and to improve the cardiometabolic treatment response and adherence.

1. Introduction

Depression is a common condition in México [1] with a prevalence of 5.8% in a national survey; it is more frequent in women compared with men, 7.8% vs 2.5% [2]. However its prevalence is higher in diabetic patients which more than 30% shows this condition [3]. Higher prevalence of depression has been reported in patients with metabolic syndrome which 43.6% shows depressive symptoms [4]. In spite of the above mentioned, in Mexico depression is not looked for in a deliberate way at the cardiometabolic departments and we ignore which is the frequency of depression like co morbidity in patients with cardiometabolic diseases. This study addresses prevalence rates and associated correlates of depressive symptoms in a cardiometabolic department.

We hypothesized that depression would be common in the cardiometabolic settings in México, and that it would associate significantly with metabolic and vascular co morbidities.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in a Cardiometabolic Department in Mexico in a university-affiliated clinic. The institutional review boards approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

2.2. Selection of Participants

Consecutive 180 patients who were treated in a Cardiometabolic Department during a year were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were being aged 18 years or older, compliant with the standard procedures of the cardiometabolic department and having the ability to response the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

2.3. Data Collection

Professional trained physicians assessed patients’ demographic and physical characteristics (age, sex, weight, height, body mass index, abdominal perimeter, and blood pressure). To examine the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week, the 21 items BDI in a validated spanish version was included [5]. The BID distinguish depressed from non-depressed patients [6]. The standard cut-off point is 10, with scores at or above that value suggesting current depression. This cut-off score was shown to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 92% for detecting depression in primary care settings [7]. Depression was classified in three grades: 10 - 18 points = mild depression, 19 - 29 points = moderate depression, ≥ 30 points = severe depression. The BDI was carried out by a trained physician who helps patients to respond the inventory. Fast glycaemia, two-hour postprandial glycaemia, fasting insulin, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), urea, creatinina, uric acid, urine analysis, microalbuminuria and haematological tests were carried out by an external certified laboratory. To assess insulin resistance (IR) the homeostasis method assessment (HOMA) was carried out [8]. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was estimated by Friedewald’s formula [9]. To assess atherosclerosis and vasomotor endothelial function, carotid intimae-media thickness and brachial flow dependent vasodilation were measured by means of high resolution Doppler ultrasound in agreement with standard international guidelines [10,11]. Ultrasound evaluations were made in an external image diagnostic centre by one certified radiologist.

2.4. Primary Data Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS, Inc (Cary, NC). Data are presented as proportions and means (with standard deviation). Student’s t test, Kruskal-Wallis, X2, and Fisher’s exact tests were used, as appropriate. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables associated with depression were evaluated by means of prevalence odds ratios (OR) and are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

3. Results

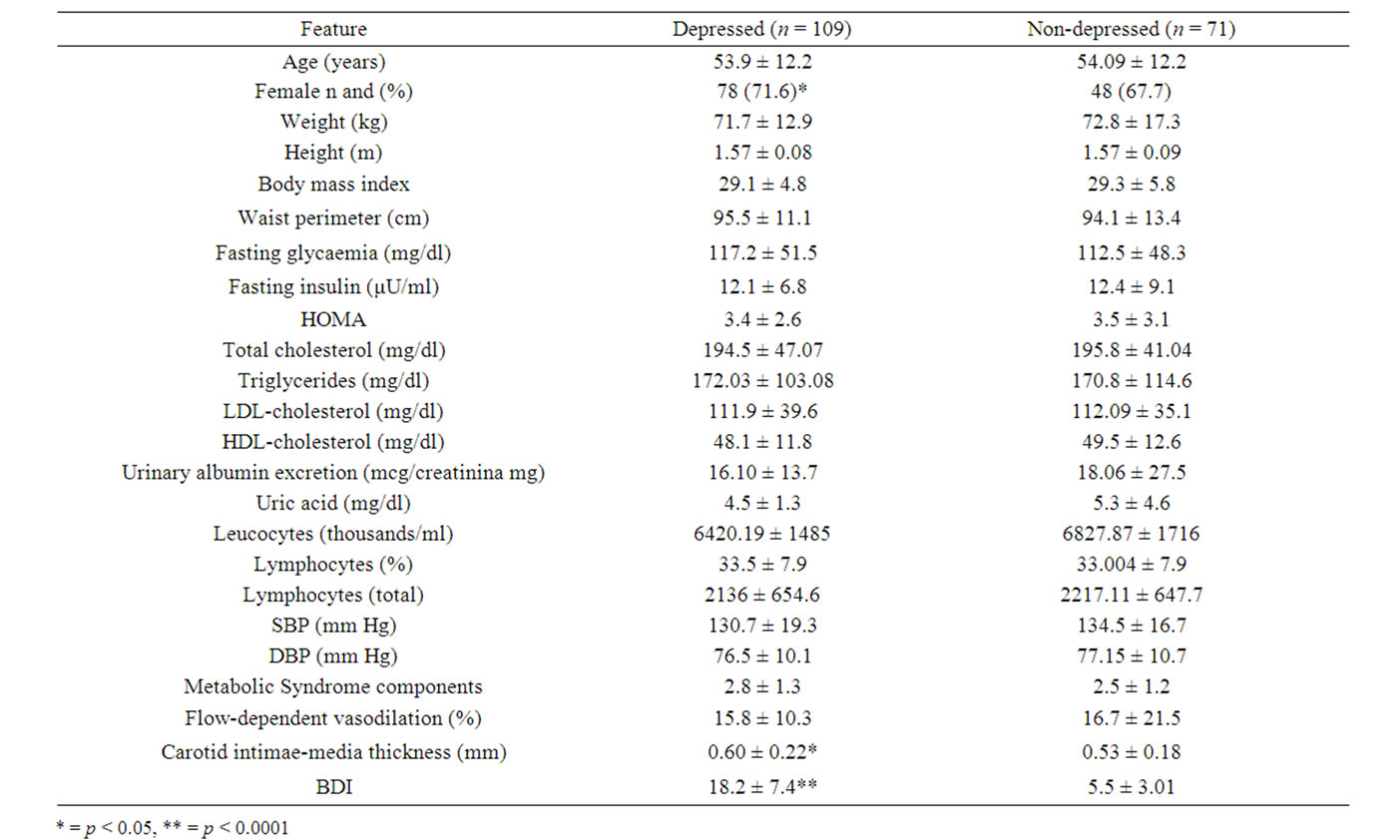

One hundred and eighty patients were evaluated. Among these patients 109 showed depressive symptoms (60.5%), 62 (56.8%) had mild, 38 (34.8%) moderate and 9 (8.2%) severe depression. Table 1 shows that there were a higher proportion of women among depressed patients, and also they had higher values of carotid intimae-media and non

Table 1. Features of depressive versus non-depressive patients from a cardiometabolic department.

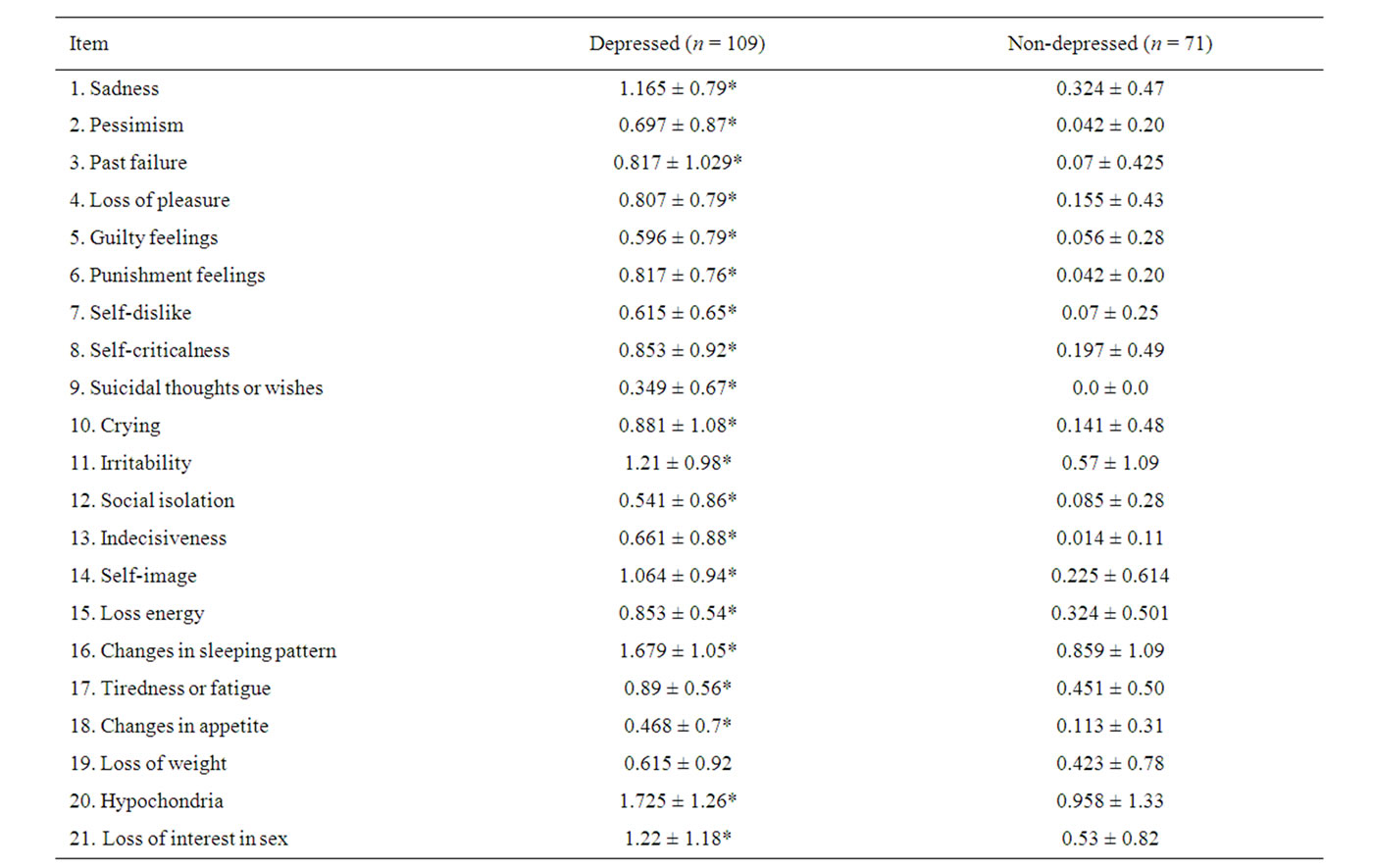

Table 2. BDI score among depressed and non-depressed patients.

depressed patients, items 20 (hypochondria), 16 (sleep disturbances), 21 (decreased libido), 11 (irritability), 1 (sadness) and 14 (deterioration of self-image) had the higher scores among depressed patients; while items 9 (suicidal tendency), 18 (changes in appetite) and 5 (guilty feelings) showed the lowest scores. Only item 19 (loss of weight) did not discriminate between depressive and nondepressive subjects. Table 3 shows that depressed patients had higher frequency of obesity,disglucemia,hypercholesterolemia, hypoalphalipoproteinemia, microalbuminuria, high uric acid levels, carotid atherosclerosis, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome; but less proportion of hypertrglicerydemia and endothelial dysfunction than non-depressed patients. There were no differences in prevalence of neither diabetes nor hypertension among depressed and non-depressed subjects. Table 4 illustrates the OR and CI from the clinical, metabolic and vascular variables related to depression prevalence in our patients; it did not show any significant association between them.

4. Discussion

These data show that a substantial proportion of patients in a Cardiometabolic Department in México had positive symptoms for depression. The prevalence of depressive symptoms as reported by cardiometabolic patients was 60.5%, higher than reported by Mexican national survey (3.3%) and by Dumbar (10%) [12], Hildrum (6.9%) [13] and by our group (46.3%) in patients with metabolic syndrome. Our results not only demonstrate that the prevalence of depressive symptoms is elevated among cardiometabolic patients, but it also identifies several factors with higher prevalence among patients with depression.

Our trial, in agreement with prior epidemiological studies, indicates that depressive symptoms are more frequent in the female sex even in general population as in Mexican patients with metabolic syndrome [4]. As previously reported [14] carotid atherosclerosis measured by means of intima-media thickness, a marker of subclinical vascular damage was positively associated with depression, we founded a light but significantly higher frequency of carotid atherosclerosis among depressed patients. Although we did not found a statistically significant association between depression and cardiometabolic features, there were a higher frequency of markers and compounds of

Table 3. Cardiometabolic alterations of depressive versus non-depressive patients from a cardiometabolic department, n (%).

Table 4. Prevalence odds ratios of measured variables related to depression symptoms among cardiometabolic department patients.

insulin resistance metabolic syndrome in patients with depression symptoms compared with non-depressed subjects. Most of them are associated with obesity as a pathogenic common basis. Obesity has been proved as a risk factor in the depressive patients, in a longitudinal study [15] at age 70 years, 35% of participants (6820 men and 3346 women) who had common mental health disorders (anxiety and depression), were obese compared with 27% of those without mental disorders (odds ratio, 1.46). There are several explanations for addressing the relationship between depression and cardiometabolic disturbances, one is the activation of hypothalamic-pituitaryadreno-cortical (HPA) axis which has been consistently docu-mented to be hyperactive in depressed patients, with elevated corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) in cerebrospinal fluid, decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) response to CRF challenge, nonsupression of cortisol secretion in response to dexamethasone, hipercortisolemia, and pituitary and adrenal gland enlargement [16-18]. Sympatoadrenal hyperactivity has also been demonstrated in depressed patients [19]. Cortisol and cathecolamines may account for central obesity, blood pressure elevation, hyperglucemia and dislipidaemia in depressed patients and they may play a significant role in the effect of depression on the development and prognosis of cardiovascular disease [20].

Central obesity is a systemic inflammatory state in which there is release of cytokines as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tissue necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Inflammation might actually cause depression by means of local (Thomas 2000) or systemic effects (Leonard 2001). Although it seems likely that inflammation impacts the progression of cardiovascular disease, it remains unclear whether the inflammation seen in depressed patients is a result of the stress response or whether inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of depression.

5. Conclusions

Depression symptoms have high prevalence in cardometabolic patients in México. Depressed patients have higher prevalence of several metabolic and vascular disturbances related to metabolic syndrome. The elevated frequency of metabolic and subclinical vascular changes in adults with symptoms of depression, stressed the need for considering depression in risk factor profiling.

REFERENCES

- M. E. Medina-Mora, G. Borges, C. Lara Muñoz, C. Benjet, J. Blanco Jaimes, C. Fleiz Bautista, J. Villatoro Velázquez, E. Rojas Guiot, J. Zambrano Ruíz, L. Casanova Rodas, S. Aguilar-Gaxiola, “Prevalencia de Trastornos Mentales y Uso de Servicios: Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Epidemiología Psiquiátrica en México,” Salud Mental, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2003, pp. 1-16.

- L. M. Bello, E. Puentes-Rosas, M. E. Medina-Mora and R. Lozano, “Prevalencia y Diagnóstico de Depresión en Población Adulta en México,” Salud Pública Mexico, Vol. 47, Suppl. 1, 2005, pp. S4-S11.

- Téllez Zenteno José Francisco, Morales Buenrostro Luís Eduardo, H. Cardiel Mario, “Frecuencia y Factores de Riesgo Para Depresión en Pacientes con Diabetes Mellitus Tipo 2 en un Hospital de Tercer Nivel de Atención,” Medicina Interna de México Marzo, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2001, pp. 54-62.

- S. M. López, H. Alveano and J. Carranza, “Prevalencia de Síntomas Depresivos en Síndrome Metabólico,” Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2008, pp. 124-133.

- S. Bonicatto, A. M. Dew and J. J. Soria, “Analysis of the Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Beck Depression Inventory in Argentina,” Psychiatry Research, Vol. 79, 1998, pp. 277-285. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00047-X

- R. C. Arnau, M. W. Meagher, M. P. Norris and R. Bramson, “Psychometric Evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with Primary Care Medical Patients,” Health Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2001, pp. 112-119. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.20.2.112

- L. K. Sharp and M. S. Lipsky, “Screening for Depression Across the Lifespan: A Review of Measures for Use in Primary Care Settings,” American Family Physician, Vol. 66, No. 6, 2002, pp. 1001-1009.

- E. Bonora, G. Formentini, F. Calcaterra, S. Lombardi, F. Marini, L. Zenari, et al. “HOMA-Estimated Insulin Resistance is an Independent Predictor of Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetic Subjects: Prospective Data from the Verona Diabetes Complications Study,” Diabetes Care, Vol. 25, No. 7, 2002, pp. 1135-1141. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.7.1135

- W. T. Friedewald, R. I. Levy and D. S. Fredrickson “Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, without Use of Preparative Ultracentrifuge,” Clinical Chemistry, Vol. 18, No. 6, 1972, pp. 499-502.

- K. Al-Shali, A. A House, A. J. Hanley, H. M. Khan, S. B. Harris, M. Mamakeesick, et al., “Differences between Carotid Wall Morphological Phenotypes Measured by Ultrasound in One, Two and Three Dimensions,” Atherosclerosis, Vol. 178, No. 2, 2005, pp. 319-325. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.016

- M. C. Correti, T. J. Anderson, E. J. Benjamin, D. C. Celermajer, F. Charbonneau, M. A. Creager, et al., “Guidelines for the Ultrasound as Sessment of Endothelial-Dependent Flow-Mediated Vasodilation of the Brachial Artery,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2002, pp. 257-265. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01746-6

- J. A. Dunbar, P. Reddy, N. Davis-Lameloise, B. Philpot, T. Laatikainen, et al., “Depression: An Important Comorbidity with Metabolic Syndrome in a General Population,” Diabetes Care, Vol. 31, No. 12, 2008, pp. 2368- 2373. doi:10.2337/dc08-0175

- B. Hildrum, A. Mykletun, K. Midthjell, K. Ismail and A. A. Dahl, “No Association of Depression and Anxiety with the Metabolic Syndrome: The Norwegian HUNT Study,” Acta Psychiatr Scand, Vol. 120, No. 1, 2009, pp. 14-22. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01315.x

- A. A. Kabir, S. R. Srinivasan, A. Sultana, W. Chen, C. Y. Wei and G. S. Berenson, “Association between Depression and Intima-Media Thickness of Carotid Bulb in Asymptomatic Young Adults,” The American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 122, No. 12, 2009, pp. 1151 e1-e8.

- M. Kivimäki, G. D. Batty, A. Singh-Manoux, A. G. Tabak, T. N. Akbaraly, J. Vahtera, M. G. Marmot and M. Jokela, “Association between Common Mental Disorder and Obesity over the Adult Life Course,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 195, No. 2, 2009, pp. 149-155. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.057299

- P. M. Plotsky, M. J. Owens and C. B. Nemeroff, “Psychoneuroendocrinology of Depression. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis,” Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1998, pp. 293-307.

- L Arborelius, M. J. Owens, P. M. Plotsky and C. B. Nemeroff, “The Role of Corticotropin-Releasing Factor in Depression and Anxiety Disorders,” Journal of Endocrinology, Vol. 160, No. 1, 1999, pp. 1-12. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1600001

- U. Ehlert, J. Gaab and M. Heinrichs, “Psychoneuroendocrinological Contributions to the Etiology of Depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Stress-Related Bodily Disorders: The Role of the Hypothalamus-PituitaryAdrenal Axis,” Biological Psychology, Vol. 57, No. 1-3, 2001, pp. 141-152. doi:10.1016/S0301-0511(01)00092-8

- P. W. Gold, K. E. Gabry, M. R. Yasuda, G. P. Chrousos: “Divergent Endocrine Abnormalities in Melancholic and Atypical Depression: Clinical and Pathophysiologic Implications,” Endocrinology Metabolism Clinics of North America, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2000, pp. 37-62. doi:10.1016/S0889-8529(01)00022-6

- E. S. Brown, F. P. Varghese and B. S. McEwen, “Association of Depression with Medical Illness: Does Cortisol Play a Role?” Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 55, No. 1, 2004, pp. 1-9. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00473-6