Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol.3 No.7(2013), Article ID:36543,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojog.2013.37101

Canadian university students’ perceptions of future personal infertility

1Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

2Institute of Population Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Email: *Karen.Phillips@uottawa.ca

Copyright © 2013 Amanda N. Whitten et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 24 June 2013; revised 22 July 2013; accepted 30 July 2013

Keywords: Infertility; University Students; Culture; Gender

ABSTRACT

Objective: University is a time for self-discovery, development of independence and transition to adulthood. It is not well examined whether childless university students also consider the potential of future personal infertility. The objective of this study was to document expectations and perceptions related to personal infertility in a sample of young adults. Methods: Using a qualitative approach, interviews were conducted with 39 male and female university students in Ottawa, Canada. Interview topics included contemplation of personal infertility, anticipated gendered experience of infertility and cultural perceptions of infertility. Results: The possibility of future infertility was not contemplated by most participants (74%). Although students generally expected infertility to be an emotional experience, women especially anticipated that infertility would be associated with negative gender identity and reduced self-esteem. Ethnic-minority participants from pro-natalist countries perceived infertility to be stigmatized by their communities, particularly against women. Conclusions: This sample of childless young adults anticipated many gendered and cultural dimensions of the experience of infertility, suggesting that these perceptions are shaped well in advance of contemplation of family planning.

1. INTRODUCTION

University years are a time for self-maturation and transition to adulthood including exploration of identity and sexuality [1]. Sexual encounters are pleasure or relationship-driven, protected by often inconsistent use of condoms or birth control methods reflecting attempts to avoid pregnancy [1]. These young adults are at highest risk by age (individuals under the age of 30) for sexually transmitted infections (STI) [2]. STI are well-established risk factors for female infertility [3,4], with evidence somewhat unclear for male infertility [5]. University students’ awareness of infertility and associated risk factors, including STI, has been previously examined in studies from Sweden [6-8], Finland [9], Italy [10], United States [11], United Kingdom (UK) [12], Israel [13] and Canada [14]. Young adults generally understand what is meant by infertility but have difficulties identifying risk factors and most overestimate the age at which female fertility declines [6-14]. The emphasis of these quantitative studies on infertility risk factors has rarely provided opportunity to explore contemplations of personal infertility with this population. Future personal infertility was a concern for 40.3% of Toronto high school students [15] and 72% of US female adolescents [16]. However, only 25% of US university students identified infertility as a potential obstacle to obtaining their preferred future family size [11]. Awareness and contemplation of infertility inform lifestyle modifications that may reduce infertility risk factors [17,18].

Infertility impacts individual life experiences beyond the biological difficulties with conception. A diagnosis of infertility can impact self-esteem, perceptions of gender identity and gender role. Female self-perception, identity and sexuality have been well examined in terms of reproductive choices including the decision to become mothers [19]. The role of motherhood is perceived as “natural” and a biological destiny, setting the stage for societal and personal conflicts when women are childless by choice or infertile [19,20]. Parenthood is similarly a gendered experience for men, linked to virility, masculinity, authority and power [20,21]. Male infertility has been suggested to be associated with decreased selfperceptions of masculinity, feelings of weakness, inadequacy and impotence [21-24].

Infertility is an emotionally difficult diagnosis, further complicated by cycles of hope and despair associated with assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [25-29]. Emotional supports provided through social networks including partner, friends, family and community are essential throughout this period [28,30]. Parenthood and fertility are central to many societies’ cultural and gender norms. For some cultures, negative attitudes and perceptions of infertility can be at times severe, particularly against women, producing stigma, ostracism and divorce [26]. In multicultural societies such as Canada, immigrant men and women, diagnosed with infertility, may be challenged by sometimes dichotomous birth and adopted cultures [31,32]. Similarly, first generation Canadians may be influenced by parents’ cultural perceptions of infertility.

The perspectives of university students relating gender and culture to future infertility remain a gap in the literature. University students are uniquely on the threshold of adulthood and are still very much influenced by parental norms [33]. A qualitative approach was used to discuss future infertility with a multi-ethnic sample of Ottawa University undergraduate students.

2. METHODS

2.1. Recruitment

Thirty-nine undergraduate students from a university in Ottawa, Canada were recruited using posters, Facebook advertisements, snowball technique and purposive sampling to ensure gender and ethnic diversity. Participants were provided with a summary of the research study, details related to institutional ethics review board approval and contact information for the research team. All participants signed consent forms prior to being interviewed. Nominal financial compensation was provided to reimburse participants for their time.

2.2. Data Collection

A broad, overarching study was designed to qualitatively examine university students’ perceptions, knowledge and understanding of infertility, risk factors and infertility treatments. The data presented here are a subset of the larger study findings. Four interview questions were posed to respondents in 2008: 1) Have you ever thought about infertility as a personal concern? 2) If you have a partner, have you ever talked together about infertility? 3) If you were infertile how would that make you feel? As a man/woman? 4) How is infertility viewed by your cultural group? Demographic data were also collected and are presented in Table 1. Individual, semi-structured

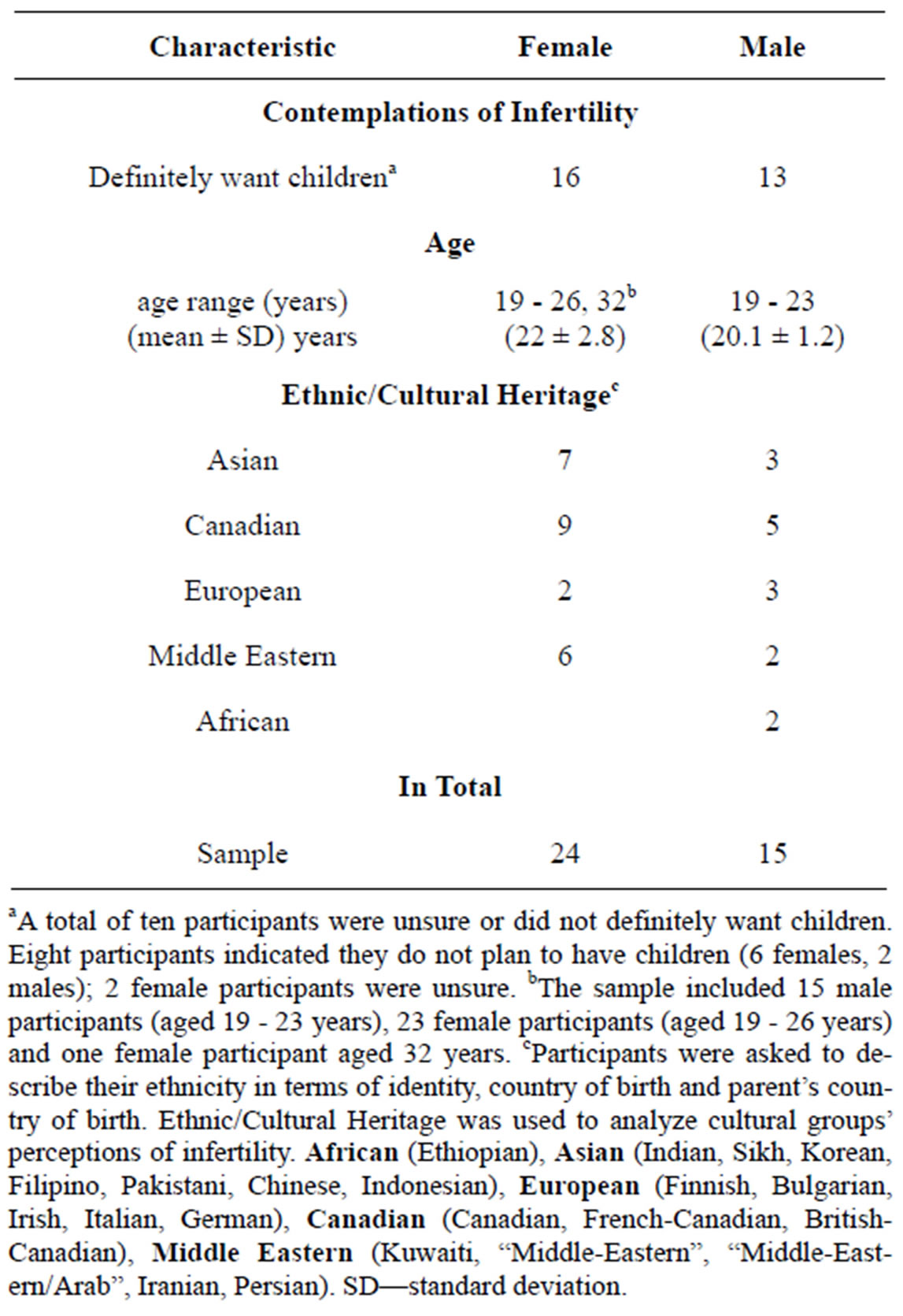

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

aA total of ten participants were unsure or did not definitely want children. Eight participants indicated they do not plan to have children (6 females, 2 males); 2 female participants were unsure. bThe sample included 15 male participants (aged 19 - 23 years), 23 female participants (aged 19 - 26 years) and one female participant aged 32 years. cParticipants were asked to describe their ethnicity in terms of identity, country of birth and parent’s country of birth. Ethnic/Cultural Heritage was used to analyze cultural groups’ perceptions of infertility. African (Ethiopian), Asian (Indian, Sikh, Korean, Filipino, Pakistani, Chinese, Indonesian), European (Finnish, Bulgarian, Irish, Italian, German), Canadian (Canadian, French-Canadian, BritishCanadian), Middle Eastern (Kuwaiti, “Middle-Eastern”, “Middle-Eastern/Arab”, Iranian, Persian). SD—standard deviation.

interviews were both taped and noted, followed by transcription and qualitative data analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

Transcripts were coded by interview topic using NVIVOTM (QSR International, Cambridge, MA, USA) to label major concepts, responses and perceptions. Qualitative content analysis [34] was used to identify major content themes and included both group and individual coding. The research team met regularly to ensure coding consistency and to confirm saturation [35]. Perceptions of personal infertility were further analyzed by sex. Participants’ cultural perceptions of infertility were analyzed on the basis of stated ethnic identity/country of birth/ parent’s country of birth (Ethnic/Cultural Heritage, see Table 1). Aggregation of ethnic/cultural groups was necessary for this analysis (ethnic-minorities vs “Canadian”- identified participants), however in the body of the manuscript quotations are identified using participants’ stated ethnic/cultural identities. As we did not collect data on citizenship, ethnic-minority-identified participants may be Canadian permanent residents or Canadian citizens. We have therefore used the term “Canadian” in quotations to refer to non-ethnic minority participants from Canada.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

Fifteen men (mean age 20.1 years) and twenty-four women (mean age 22 years) participated in this study (Table 1). Twenty-nine participants declared a definite intention to have children in the future. One female undergraduate participant was 32 years with no children. All participants were childless.

3.2. Contemplations of Future Infertility

Most participants were not concerned nor had ever contemplated the possibility of personal infertility.

“No. I think that’ll be something that could crop up if and when I get married or start a family. At the moment school and work first and foremost. That’s all I’ve thought about.” ID-2 male, Canadian.

“Not really because I want to have children younger and don’t have any chronic illnesses” ID-27, female, French-Canadian.

Three male and seven female participants, two of whom indicated they did not wish to have children in the future, had worried about personal infertility.

“Yes all the time because I want to study medicine and have children afterwards. So this will be a problem for me because I’ll be older. I don’t know how to cope and balance my desire [for children]” ID-26, female, Indian.

“Yeah. Well actually it’s just, I’ve always thought of my future as having kids, you never really think about the problems that can arise and then there’s people in my family who are infertile. So that’s what brought the idea.” ID-19, male, Ethiopian.

Two female participants alluded to personal health issues including polycystic ovaries and hormonal irregularities which had prompted their infertility concerns. Four participants had discussed infertility with current or former partners, prompted by personal fertility concerns.

“Oh definitely. Cause I have polycystic ovary and originally they wanted me to get a hysterectomy and I switched gynecologists pretty quickly. So yeah, I haven’t been fully diagnosed with polycystic ovary because I am obviously quite young, that’s why they put me on the pill and they definitely were concerned that I might lose my ovaries as a result of polycystic ovary. Normally I sort of bring up, especially if you’re with somebody long-term and I’ll say “look, you know, I haven’t been fully diagnosed with this condition and it’s a possibility that one day I may not be able to have kids. And take me for who I am or see you later buddy.” ID-10, female, Canadian.

Participants were asked to consider how they would feel if they were diagnosed with infertility. Emerging themes from male participants included no impact and sadness.

“It wouldn’t matter” ID-21, male, Chinese.

“I would feel bad to my wife. I would feel bad to the in-laws. They would think that...oh, this guy can’t give me a... yeah, grandkid.” ID-11, male, Indonesian.

Five ethnic-minority men anticipated that a diagnosis of infertility would make them feel less masculine or believed infertility would lower their self-esteem.

“Yeah, my self-esteem would be lowered. Just thinking that I’m unable to do something I should. So I would...like, I don’t know what’s the word... I would feel less manly.” ID-5, male Kuwaiti.

“I wouldn’t be secure in my masculinity.” ID-36, male, African-Canadian.

In contrast to most of the men, women predominantly perceived a future diagnosis of infertility as having a negative impact on their self-esteem, feelings of femininity and producing feelings of sadness.

“I think I would feel pretty bad, really bad. And I think I would feel less feminine and I would feel that my life is like, not like it was before because now I have plans, because I want to have a family, I want to have three children, and suddenly I feel like my life would be not so happy anymore because I would know that I would never be able to have children or to get pregnant.” ID-15, female, German.

“I would be pretty sad about it. I’d feel that I have the potential to be rejected for marriage purposes” ID-23, female, Indian.

“I would have low self-esteem, I’d be afraid that my partner would leave me” ID-26, female, Indian.

Women who indicated they were unsure or did not want to have children in the future did not perceive a diagnosis of infertility to have a major impact.

“It wouldn’t bug me, I don’t want to have kids” ID-30, female, Irish.

3.3. Cultural Perceptions of Infertility

Participants were asked to describe perceptions of infertility within their cultural groups. Canada was perceived as a society with no infertility stigma, whereas ethnicminorities identified cultural infertility stigma and stigma against women within their respective cultural communities. Participants who identified as “Canadian” or WestEuropean struggled with the concept of cultural group and did not perceive any societal influence on their beliefs or behaviors related to infertility.

“I wouldn’t really say I belong to a cultural group, I’m just your typical born in Canada, parents both born in Canada, grandparents...one of them was in Canada one of them wasn’t.” ID-14, female, Canadian.

The Canadian culture was not perceived to stigmatize infertility.

“I’d say, on the average, I’d say most Canadians probably couldn’t care less whether you had one kid, no kid or two kids. I think generally a lot of people would view it as something beyond your control.” ID-2, male, Canadian.

“I don’t think [infertility is] viewed as anything stigmatized. It’s a shame because if they want children, then yeah that’s a shame.” ID-13, female Canadian.

“I think [infertility is] just seen as something that happens to some people and when it does, they look at other options.” ID-16, female, Canadian.

Multi-ethnic Canadian participants recognized infertility stigma within their cultural communities.

“It depends which culture we are examining. The Lebanese/Muslim side of it, I think [infertility is] viewed poorly because a lot of them have a lot of kids, but on my Ukrainian/Jewish side I don’t think it’s viewed poorly at all. But I don’t really care what my culture or group thinks.” ID-10, female, Canadian.

“My cultural group, as in my parents’ culture? Cause my culture’s Canadian more than what my parents’ culture is, which is Caribbean and Trinidadian. In Trinidadian culture, [infertility would] probably be a negative thing more than in Canadian culture” ID-6, female, Canadian.

Participants noted infertility stigma within their Arab/ Middle Eastern, Algerian, Chinese, Ethiopian, Iranian, Kuwaiti, Indian and Pakistani cultural communities. Within Algerian, Chinese, Ethiopian, Iranian and Indian communities, infertility was described as particularly stigmatizing for women.

“I was born in Algeria so I have an Arabic background. Infertility is seen as something very unfortunate and maybe even in a way...like I would only be guessing, but maybe like it’s the woman’s fault, but again there’s also men’s fertility but I think it’s mainly viewed as a woman’s issue.” ID-3, female, Algerian-Canadian.

“Yes, just because my religion and family and community—it’s best to have lots of children, that’s kind of seen as a good thing. So to not have kids it’s kind of bad. It’s looked down upon just because everybody tends to have a very large family and fertility is seen as an advantage for people to have as much kids as they can. So if you’re infertile, it’s kind of like, you’re looked down upon.” ID-5, male, Kuwaiti.

“I think it’s viewed negatively and then I know that say, like not here, but the country where I’m from, Iran, they would expect a woman to marry young and then have children right away and then if you can’t have children, the man might just divorce you.” ID-18, female, PersianCanadian.

Ethnic-minority participants tended to identify strongly with a cultural group based on their family traditions, family origins or ethnic identity. Infertility was generally described as negatively perceived by their respective cultures. These participants anticipated that women would bear the cultural shame of infertility particularly in societies where having many children was expected. Some participants attempted to distance themselves from these cultural norms by prefacing their remarks with “I’m not religious” or identifying themselves as more “Canadian” than their parent’s ethnicity.

4. DISCUSSION

For most Ottawa young adults, personal infertility was not a significant concern. Participation in this study represented most young adults’ first contemplation of infertility. Only a few participants mentioned discussions with partners, largely driven by existing reproductive health issues. Focus on education goals and the assumption of fertility were reasons provided by several participants regarding their lack of infertility concern. Time, financial constraints and disruptions to future career goals were identified by Swedish young adults as barriers to having children during the pursuit of a university degree [6-8,36] which may explain our participants’ relative lack of concern regarding possible infertility.

When asked to anticipate the personal impacts of infertility, most Ottawa students acknowledged that infertility would be an emotional experience. Ottawa women in particular were cognizant that infertility would produce emotional distress, negative gender identity and self-esteem. These findings are consistent with a sample of childless Canadian women (mean age 28.1 years) who expected to feel “distraught” if they were unable to conceive [37]. Infertility is highly associated with emotional distress, anxiety, depression and health complaints in women [25-29]. For some women their intense desire to have children is magnified by the experience of infertility [28]. Social pressure, avoidance of young families/ pregnant women and cycles of mixed emotions, hope and despair have been consistently described as experiences of infertile women from Canada [30,38,39], US [25,40], Sweden [28], Netherlands [29], Switzerland/Germany [41], Chinese Taipei [42], Japan [43], Brazil [27], Kuwait [44] and Iran [26,45]. For some of these regions, the effects of infertility on women are more pronounced within their traditional family-based cultures. Infertile Iranian women, for example, exhibit high rates of anxiety and depression compared to other countries. This is attributed in part to the cultural importance of family status in Middle Eastern countries and the resulting stigma against infertile women [26]. South Asian (Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian) culture is also very pro-natalist with expectation that marriage will be followed immediately by childbearing [46,47]. Among our female participants, two Indian women expressed fears that they would be either rejected for marriage or left by their partner if diagnosed with infertility. Although some male participants did consider that infertility would be “letting down” their spouse and their parents by not producing grandchildren, none of the men anticipated that they would be rejected because of their fertility status. Our sample of Ottawa women correctly anticipated the significance a diagnosis of infertility would have on their emotional lives, even though they were not contemplating conception at the time of the study. Most of these women have identified a strong desire to have children which may shape their perceptions of a future with no biological children.

Most Ottawa men did not expect that infertility would be accompanied by emasculation or negative self-esteem. Similarly, a sample of older Canadian childless men (mean age 33.9 years) anticipated feeling “disappointed” rather than “upset” or “distraught” if they were unable to father a child [37]. Although many studies suggest infertile men experience negative gender identity [21,23,28, 48], men’s reactions to infertility may be more complex. A discourse analysis determined that UK media consistently conflate fertility and male potency, implicitly creating the relationship between infertility and impotence [23]. In contrast, studies from Australia report that only a subset of men diagnosed with infertility associate biological fatherhood with masculinity [22], negative impacts to their partnerships or diminished sexual satisfaction [49]. Men’s reactions to infertility may be related to the type of infertility diagnosed: male factor, female factor, combined or unexplained [50]. A diagnosis of male factor infertility may be more likely to provoke feelings of threatened masculinity [24]. Traditional cultures that construct infertility as exclusively a woman’s problem may not accept a diagnosis of male-factor infertility [51]. Within such societies, men diagnosed with infertility are suggested to experience higher emotional suffering compared to Western men [50-52]. Indeed, the few male participants who perceived that infertility would negatively impact their self-esteem or masculinity identified as ethnic-minorities. It is apparent that most men diagnosed with infertility experience diminished quality of life and mental health [22,24,50]. It seems also likely that at least some men express their grief and sadness about their infertility without feelings of emasculation [22]. Men’s reactions to infertility have been suggested to be shaped by media, formative coping strategies, culture [51] and responses to stress which include the “flight or fight” response [50]. The anticipated reactions to possible infertility by childless, Ottawa male participants, most of whom had never contemplated infertility, were very consistent with the emotional experiences of infertile men [22,24,28]. These findings suggest that gendered responses to infertility are shaped well in advance of contemplation of family planning.

Ethnicity has been described as one of the most important influences on the experience of infertility [53]. Whereas “Canadian” and West European-identified participants struggled with the concept of belonging to a cultural group, ethnic-minority participants readily identified their cultural heritage. Most non-Western cultures were described as very family-oriented and encouraging of large family size. Infertility was perceived to be a stigma within these traditional cultural communities; consistent with many reports of infertility stigma within pronatalist societies [26,31-32,46-47,51,53]. Some participants distanced themselves from these cultural perceptions stating they were “Canadian” or “not very religious”. In Western multicultural societies, infertility is associated with greater emotional distress in immigrants compared to infertile Western couples [51,53]. The emotional impacts of infertility experienced by Turkish immigrants living in the Netherlands, for example, are similar to the experiences of infertile couples residing in Turkey [51]. This reflects the considerable influence of a pro-natalist culture on immigrants’ emotional experience of infertility [51,53]. In the event of future infertility, ethnic-minority Ottawa participants’ experiences may be influenced by their parents, relatives and cultural communities regardless of Canadian acculturation.

Algerian, Iranian, Indian, Ethiopian and Chinese cultures were perceived to specifically stigmatize infertile women by both male and female participants with these ethnic backgrounds. Inability to produce children has been reported as cause for divorce or second marriage in Islamic societies [26,44]. Infertile Kuwaiti women feel they have failed as mothers and face possible divorce, violence and significant community stigma [44]. Infertile women in these Islamic societies experience significant family and community stigma, marital instability and abuse [26,31,44,54]. South Asian women living in Britain describe divorce, social ostracism and the possibility of their husbands taking additional wives as possible consequences of infertility [55]. It is evident that within Canada, ethnic-minority participants perceive that women within their cultural groups will not be fully supported by their communities in the event of infertility. In stark contrast, Western participants perceived that Canadian society viewed infertility as sad or unfortunate, could be addressed by fertility treatments or adoption and was an issue that warranted family and community support. These findings suggest that young adults’ awareness of community infertility support or stigma occurs prior to family planning.

Limitations

Interviewing participants about their perceptions of infertility was a valuable method to capture attitudes and beliefs, but there were some methodological limitations. This group of young adults was privileged in terms of university education, access to campus sexual and reproductive health information and the resources of the large urban setting of this study. A greater proportion of an age-matched cohort with no post-secondary education would have already initiated parenthood [56] and could draw directly from their fertility experiences. The study was intrinsically heteronormative and excluded the perspectives and experiences of sexually marginalized young adults. For some participants, their desire not to have children may have reflected their sexual identities and perceptions that infertility treatments may be limited to heterosexual couples [57].

Efforts to maximize ethnic diversity ensured few participants from any single cultural group preventing generalization of specific ethnocultural perceptions of infertility. We have therefore restricted discussions to general trends between ethnic-minority and “Canadian”-identified groups. We did not collect data on the duration of Canadian residency, and so we must further consider our ethnic participants uniquely heterogeneous with respect to Canadian acculturation, perhaps fostered by local matriculation in secondary schools, language, country of birth, religious beliefs and individual adherence to the religious and cultural values of their families. It is challenging to fully characterize the cultural impacts on participants’ perceptions of infertility, particularly within a multicultural, Western context. Ethnicity alone cannot represent the complexity of the ethnocultural familial environment, including language, parental-foreign born status and religiosity [58].

5. CONCLUSION

Students in Ottawa University anticipated that personal infertility would be an emotional experience. The ethnic diversity of the sample provided a unique opportunity to assess gender and cultural perceptions related to infertility. Women expected more significant impacts of infertility including negative self-esteem and gender identity. Ethnic-minority participants perceived that infertility is stigmatized by their cultural communities. Infertility stigma for women was also acknowledged to be prevalent within certain pro-natalist societies. Gender and cultural perceptions of infertility appear to be anticipated prior to contemplation of family planning.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding was provided by a grant from the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa.

REFERENCES

- O`Sullivan, L.F., Udell, W., Montrose, V.A., Antoniello, P. and Hoffman, S. (2010) A cognitive analysis of college students’ explanations for engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 1121-1131. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9493-7

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2009) Executive summary—Report on sexually transmitted infections in Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/sti-its-surv-epi/sum-som-eng.php

- Paavonen, J. (2012) Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the female genital tract: State of the art. Annals of Medicine, 44, 18-28. doi:10.3109/07853890.2010.546365

- Elford, K.J. and Spence, J.E. (2002) The forgotten female: Pediatric and adolescent gynecological concerns and their reproductive consequences. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 15, 65-77. doi:10.1016/S1083-3188(01)00146-2

- Ochsendorf, F.R. (2008) Sexually transmitted infections: Impact on male fertility. Andrologia, 40, 72-75. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2007.00825.x

- Tydén, T., Svanberg, A.S., Karlström, P.O., Lihoff, L. and Lampic, C. (2006) Female university students’ attitudes to future motherhood and their understanding about fertility. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 11, 181-189. doi:10.1080/13625180600557803

- Lampic, C., Svanberg, A.S., Karlström, P. and Tydén, T. (2006) Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Human Reproduction, 21, 558-564. doi:10.1093/humrep/dei367

- Svanberg, A.S., Lampic, C., Karlström, P.O. and Tydén, T. (2006) Attitudes toward parenthood and awareness of fertility among postgraduate students in Sweden. Gender Medicine, 3, 187-195. doi:10.1016/S1550-8579(06)80207-X

- Virtala, A., Vilska, S., Huttunen, T. and Kunttu, K. (2011) Childbearing, the desire to have children, and awareness about the impact of age on female fertility among Finnish university students. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 16, 108-115. doi:10.3109/13625187.2011.553295

- Rovei, V., Gennarelli, G., Lantieri, T., Casano, S., Revelli, A. and Massobrio, M. (2010) Family planning, fertility awareness and knowledge about Italian legislation on assisted reproduction among Italian academic students. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 20, 873-879. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.03.024

- Peterson, B.D., Pirritano, M., Tucker, L. and Lampic, C. (2012) Fertility awareness and parenting attitudes among American male and female undergraduate university students. Human Reproduction, 27, 1375-1382. doi:10.1093/humrep/des011

- Bunting, L. and Boivin, J. (2008) Knowledge about infertility risk factors, fertility myths and illusory benefits of healthy habits in young people. Human Reproduction, 23, 1858-1864. doi:10.1093/humrep/den168

- Hashiloni-Dolev, Y., Kaplan, A. and Shkedi-Rafid, S. (2011) The fertility myth: Israeli students’ knowledge regarding age-related fertility decline and late pregnancies in an era of assisted reproduction technology. Human Reproduction, 26, 3045-3053. doi:10.1093/humrep/der304

- Bretherick, K.L., Fairbrother, N., Avila, L., Harbord, S.H. and Robinson, W.P. (2010) Fertility and aging: Do reproductive-aged Canadian women know what they need to know? Fertility and Sterility, 93, 2162-2168. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.064

- Quach, S. and Librach, C. (2008) Infertility knowledge and attitudes in urban high school students. Fertility and Sterility, 90, 2099-2106. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.024

- Trent, M., Millstein, S.G. and Ellen, J.M. (2006) Gender-based differences in fertility beliefs and knowledge among adolescents from high sexually transmitted disease-prevalence communities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 282-287. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.012

- Foster, W.G., Neal, M.S., Han, M.S. and Dominguez, M.M. (2008) Environmental contaminants and human infertility: hypothesis or cause for concern? Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part B, Critical Reviews, 11, 162-176. doi:10.1080/10937400701873274

- Tough, S., Tofflemire, K., Benzies, K., Fraser-Lee, N. and Newburn-Cook, C. (2007) Factors influencing childbearing decisions and knowledge of perinatal risks among Canadian men and women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11, 189-198. doi:10.1007/s10995-006-0156-1

- Koert, E. and Daniluk, J.C. (2010) Sexual transitions in the lives of adult women. In: Miller, T.W., Ed., Handbook of Stressful Transitions across the Lifespan, Springer, New York, 235-252. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0748-6_12

- Daniluk, J.C. (2003) Creating a life. In: Women’s sexuality across the Lifespan: Challenging Myths, Creating Meanings, Guilford Press, New York, 163-185.

- Dudgeon, M.R. and Inhorn, M.C. (2003) Gender, masculinity and reproduction: Anthropological perspectives. International Journal of Men’s Health, 2, 31-56. doi:10.3149/jmh.0201.31

- Fisher, J.R.W., Baker, G.H.W. and Hammarberg, K. (2010) Long-term health, well-being, life satisfaction, and attitudes toward parenthood in men diagnosed as infertile: Challenges to gender stereotypes and implications for practice. Fertility and Sterility, 94, 574-580. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.165

- Gannon, K., Glover, L. and Abel, P.D. (2004) Masculinity, infertility, stigma and media reports. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 1169-1175. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.015

- Smith, J.F., Walsh, T.J., Shindel, A.W., Turek, P.J., Wing, H., Pasch, L. and Katz, PP. and Infertility Outcomes Program Project Group (2009) Sexual, marital, and social impact of a man’s perceived infertility diagnosis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 2505-2515. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01383.x

- Casey Jacob, M., McQuillan, J. and Griel, A.I. (2007) Psychological distress by type of fertility barrier. Human Reproduction, 22, 885-895. doi:10.1093/humrep/del452

- Ramezanzadeh, F., Aghssa, M.M., Abedinia, N., Zayeri, F., Khanafshar, N. and Jafarbadi, M. (2004) A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC Women’s Health, 4, 9-18. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-4-9

- Franco Jr., J.G., Razera Baruffi, R.L., Mauri, A.L., Petersen, C.G., Felipe, V. and Garbellini, E. (2002) Psychological evaluation test for infertile couples. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 19, 269-23. doi:10.1023/A:1015706829102

- Hjelmstedt, A., Andersson, L., Skoog-Svanberg, A., Bergh, T., Boivin, J. and Collins, A. (1999) Gender differences in psychological reactions to infertility among couples seeking IVFand ICSI-treatment. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 78, 42-48. doi:10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780110.x

- Lechner, L., Bolman, C. and van Dalen, A. (2007) Definite involuntary childlessness: associations between coping, social support and psychological distress. Human Reproduction, 22, 288-294. doi:10.1093/humrep/del327

- Peterson, B.D., Newton, C.R., Rosen, K.H. and Skaggs, G.E. (2006) Gender differences in how men and women who are referred for IVF cope with infertility stress. Human Reproduction, 21, 2443-2449.

- Inhorn, M.C., Ceballo, R. and Nachtigall, R. (2009) Marginalized, invisible, and unwanted: American minority struggles with infertility and assisted conception. In: Culley, L., Hudson, N. and Van Rooij, F., Eds., Marginalized Reproduction: Ethnicity, Infertility and Reproductive Technologies, Earthscan, Sterling, 181-197.

- Inhorn, M.C. and Birenbaum-Carmeli, D. (2008) Assisted reproductive technologies and culture change. Annual Review of Anthropology, 37, 177-196. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.37.081407.085230

- Mitchell, B.A. (2006) Changing courses: The pendulum of family transitions in comparative perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 37, 325-343.

- Sandelowski, M. (2000) Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 334-340. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Morse, J.M. (1994) Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S., Eds., Handbook of Qualitative Inquiry, Sage Publications Ltd., Thousand Oaks, 220-235.

- Skoog, S.A., Lampic, C., Karlström, P.O. and Tydén, T. (2006) Attitudes toward parenthood and awareness of fertility among postgraduate students in Sweden. Gender Medicine, 3, 187-195. doi:10.1016/S1550-8579(06)80207-X

- Daniluk, J.C. and Koert, E. (2012) Childless Canadian men’s and women’s childbearing intentions, attitudes towards and willingness to use assisted human reproduction. Human Reproduction, 27, 2405-2412. doi:10.1093/humrep/des190

- Daniluk, J.C. (1997) Helping patients cope with infertility. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology, 40, 661-672. doi:10.1097/00003081-199709000-00025

- Harris, D.L. and Daniluk, J.C. (2010) The experience of spontaneous pregnancy loss for infertile women who have conceived through assisted reproduction technology. Human Reproduction, 25, 714-720. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep445

- Lukse, M. and Vacc, N. (1999) Grief, depression, and coping in women undergoing infertility treatment. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 93, 245-251.

- Hämmerli, K., Znoj, H. and Berger, T. (2010) What are the issues confronting infertile women? A qualitative and quantitative approach. Qualitative Report, 15, 766-782.

- Lin, Y. (2002) Counselling a Taiwanese woman with infertility problems. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 15, 209-215. doi:10.1080/09515070110104024

- Matsubayashi, H., Hosaka, T., Izumi, S.I., Suzuki, T., Kondo, A. and Makino, T. (2004) Increased depression and anxiety in infertile Japanese women resulting from lack of husband’s support and feelings of stress. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26, 398-404. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.05.002

- Fido, A. and Zahid, M.A. (2004) Coping with infertility among Kuwaiti women: Cultural perspectives. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 50, 294-300. doi:10.1177/0020764004050334

- Nasseri, M. (2000) Cultural similarities in psychological reactions to infertility. Psychological Reports, 86, 375- 378. doi:10.2466/pr0.2000.86.2.375

- Culley, L. and Hudson, N. (2009) Commonalities, differences and possibilities culture and infertility in British South Asian communities. In: Culley, N.L. and Van Rooij, F.H., Eds., Marginalized Reproduction: Ethnicity, Infertility and Reproductive Technologies, Earthscan, Stirling VA, 97-116.

- Culley, L., Hudson, N., Rapport, F.L., Katbamna, S. and Johnson, M.R.D. (2006) British South Asian communities and infertility services. Human Fertility, 9, 37-45. doi:10.1080/14647270500282644

- Dooley, M., Nolan, A. and Sarma, K.M. (2011) The psychological impact of male factor infertility and fertility treatment on men: A qualitative study. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 32, 14-24. doi:10.1080/03033910.2011.611253

- Hammarberg, K., Baker, H.W.G. and Fisher, J.R.W. (2010) Men’s experiences of infertility and infertility treatment 5 years after diagnosis of male factor infertility: A retrospective cohort study. Human Reproduction, 25, 2815-2820. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq259

- Wischmann, T. (2013) ‘Your count is zero’—Counselling the infertile man. Human Fertility, 16, 35-39. doi:10.3109/14647273.2013.776179

- van Rooij, F.B., Van Balen, F. and Hermanns, J.M. (2007) Emotional distress and infertility: Turkish migrant couples compared to Dutch couples and couples in Western Turkey. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 28, 87-95. doi:10.1080/01674820701410015

- van Rooija, F.B., van Balen, F. and Hermannsa, J.M.A. (2004) A review of Islamic Middle Eastern migrants: Traditional and religious cultural beliefs about procreation in the context of infertility treatment. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 22, 321-331. doi:10.1080/02646830412331298369

- Vanderlinden, L.K. (2009) German genes and Turkish traits: Ethnicity, infertility, and reproductive politics in Germany. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 266-273. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.027

- Douki, S., Ben, Z.S., Nacef, F. and Halbreich, U. (2007) Women’s mental health in the Muslim world: Cultural, religious, and social issues. Journal of Affective Disorders, 102, 177-189. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.027

- Culley, L. and Hudson, N. (2009) Constructing relatedness: Ethnicity, gender and third party assisted concepttion in the UK. Current Sociology, 57, 249-267. doi:10.1177/0011392108099165

- Andres, L. and Adamuti-Trache, M. (2008) Life-course transitions, social class, and gender: A 15-year perspective of the lived lives of Canadian young adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 11, 115-145. doi:10.1080/13676260701800753

- Ross L.E., Steele L.S., and Epstein R. (2006) Lesbian and bisexual women’s recommendations for improving the provision of assisted reproductive technology services. Fertility and Sterility, 86, 735-738. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.049

- Mitchell, B.A. (2004) Making the move: Cultural and parental influences on Canadian young adults’ home leaving. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35, 423- 443.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.