Psychology

Vol.5 No.12(2014), Article

ID:49317,7

pages

DOI:10.4236/psych.2014.512152

Social Development in a Game Context

Ana Lucia Petty, Maria Thereza C. C. de Souza

Institute of Psychology, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Email: anapetty@dialdata.com.br, mtdesouza@usp.br

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 June 2014; revised 21 July 2014; accepted 11 August 2014

ABSTRACT

Social development is a fundamental subject that challenges professionals who work with children and teenagers. Questions such as how to behave adequately, what limits must be defined, and at the same time, how to stimulate autonomy and create a cooperative environment, are daily made, but solutions are not always satisfactory. The aim of this paper is to present a possible contribution to the discussion, describing highlights of a successful initiative. The practice in seeing children with learning disabilities at the Laboratory of Studies about Development and Learning (University of Sao Paulo), also identifies the same questions and there is a permanent search for creative solutions. For the last 25 years, groups of children from the Fundamental School were seen by professionals who organized activities in a game context, challenging them to play, develop reasoning and construct favourable attitudes. Results show that playing games in an intervention context stimulated changes in attitudes and social behaviour. As a consequence, it enabled children interact and establish a better quality of relation, based on cooperation and mutual respect.

Keywords

Social Interaction, Playing Games, Intervention

1. Introduction

The practice in seeing children at school age has shown that many learning problems occur as a result of negative interferences in the social realm. It is frequently observed that the communication between what to do and how to proceed is disrupted. Analyse development from this perspective puts in evidence a fundamental subject that challenges many professionals that work with children and teenagers. Questions such as how to guarantee adequate behaviour, what limits must be defined, what can be allowed (or not!) according to each age, and at the same time, how to stimulate autonomy and create a cooperative and respectful environment, are daily made, but solutions are not always satisfactory. The aim of this study is to present a possible contribution to the discussion, describing some highlights of a successful initiative held in a game context and developed at a laboratory of the Institute of Psychology at University of Sao Paulo.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

If one searches for information about the importance of playing games for a child, it will be easy to find many references. Huizinga (1938) and Caillois (1958) point out the relevance of playing games for humanity and describe how it becomes evident in different civilizations, taking significant part in every culture.

The central idea of Huizinga’s theory was to consider the principle in which all human beings play and it was from this point on that every civilization developed. He was absolutely convinced that games and the ludic aspect (or playful tone) were fundamental because of their significant function, meaning that the one who played considered the activity itself meaningful and worthy to be executed, and also because of the non material or concrete results, where there was no profit made after the match was over. This author has put in evidence the social characteristics of the game context to exercise the will to act, as it was not an external imposition and absorbed the player in a very particular way, situation in which he/she became momentarily apart from reality, being able to get involved, interact and follow the rules, in a determined period of time and space.

Caillois studied Huizinga’s work and recognized its importance, agreeing about the analysis in which the cultural and social aspects of the game activity were enhanced. He added many interesting contents, for example, discussing the game influence in the field of arts, politics and war, and also brought into discussion the anthropological aspects of the game context. This author associated it to different concepts, such as being at ease, having fun, not being a serious or productive situation, representing cultural manifestation, acting freely in accordance with the rules and experimenting luck and creating strategies.

Caillois has also suggested categories or types of games, such as competition, strength, chance or misfortune, ability and strategy, underlying the intrinsic characteristics of them to stimulate physical and/or intellectual capacity. The contribution of his studies to the game theory is unquestionable, for example, the definition of playing games: a free activity, limited to space and time, uncertain and unproductive, regulated by rules and not real (a fiction moment).

Chateau (1955), in his turn, studied children’s development and found out that the play aspect was always present and necessary, being expressed in different ways during childhood. As a consequence, he underlined the importance of the game activity to allow every child to develop healthy and become socialized. This author has also put the act of playing games in correspondence to adult’s work, due to how strictly children consider the challenge and rules, affirming that it influences in their attitudes and behaviour. In his view, a child that does not play becames an adult incapable to think, because of the wasted opportunity to experiment, coordinate, share and develop aspects related to motor activity, moral and social rules, cognitive functions and emotional feelings.

In opposition to Huizinga and Caillois, Chateau stated that the game context was taken seriously, many times supposed fatigue or exhaustion, and was not only for fun, but also demanded learning and represented a mysterious moment, consisting on an essential activity that favoured the development of autonomy, cooperation and mutual respect.

In the field of Developmental Psychology, two of Piaget’s books brought significant data to enhance the contribution of playing games to understand children’s behaviour and reasoning. In both of them he described the act of playing as social, spontaneous and also a necessary infant activity. “Play, dreams and imitation” (Piaget, 1945) presented a fundamental chapter in which Piaget analysed many types of games, and ended up classifying them into three main structures, considering the mental complexity inherent to each level of development: practice games, symbolic games, and games with rules, appearing in this sequence, but one includes the former and becomes more complex as the child develops. He stated that it is a growing progress, starting with mere motor play and develops to representation, verbal communication, and interiorised actions, finalising with the construction and consideration of rules, which implies social relation. In this case, rules represent a necessity in the organization of the collective play and bring a significant contribution to the descentration process.

“The moral judgement in the child” (1932) Piaget has described many researches investigating about how children distinguish right and wrong, and deal with adult authority. It was analysed the functioning of lying, cheating, punishment and responsibility, describing changes in the acceptance of the consensus rules and the pressure of the group on the individual. He brought up important data about the process of attitude change as children grow, analysing how they understood moral aspects, using marble games and stories (moral dilemmas), among other resources, as a means of making them put in evidence their thoughts, in special how they practiced rules and got more conscious about using them. As a contribution of this study, he defined different social behaviours: motor, self-centered, and cooperative, each of them corresponding to three types of rules: motor, unilateral respect, and mutual respect. According to Piaget, social development was as important as cognitive development, especially considering the moral context. He stated that to deal with rules was a fundamental task and, being so, a healthy cognitive growth would mean to construct competences that would enable the child to deal with any and every rule, no matter if it had to do with the social environment or a particular game situation.

In both books, the interpersonal relation was considered as the main condition to favour social development. Being so, the game context represented a rich and interesting opportunity to learn about how children behaved and interacted in relation to adults and peers, not leaving behind the fact that being able to deal with rules would stimulate the operational capacity and logical thinking. In a word, Piaget’s work had put in evidence the relevance of the game context to study moral judgment, the construction of rules and autonomy, and also different forms of cooperation.

1.2. On Learning from the Game Context

It has been more than 20 years since researchers from the Laboratory of Studies about Development and Learning (University of Sao Paulo) have been studying Piaget’s works and other authors that analysed the influence of play to the child development. The practice has confirmed the contribution of playing games with children, and it was possible to create a project based on this context, which includes challenges and solving problems, aiming at helping them improve attitudes in order to become better students and develop adequately (De Macedo, Petty & Passos, 1997, 2000, 2005; De Souza, Petty et al., 2002). The project (“intervention program”) consists in working per one hour every week, during three semesters, with each group of 12 children from the Fundamental School with learning difficulties, aged 7 to 11 years old. They are seen by professionals who organize the activities and interventions, challenging them to play, develop reasoning and construct favourable attitudes to the learning and developing process (Petty & De Souza, 2012).

The game context is also a rich environment to collect data about how children behave and interact. Observe them play, build up strategies, deal with rules and goals, talk among each other, compete and cooperate, enables to learn meaningful information, both: to plan the next steps of the activities and to stimulate them to change what is negative or disfavours achieving good results in the interpersonal realm. Doing so, the hypothesis is that the questions about how to interfere in pro of adequate behaviour, being able to put clear limits and simultaneously favour cooperation and autonomy, posed in the beginning of this paper, can be answered with a positive solution.

In order to acknowledge in what terms and extent was the contribution of the game context to the social development, researchers from the laboratory decided to make a qualitative research and for that, a questionnaire was created.

During the period of three semesters, data was collected at the first and the last day of each semester, and it included four categories: time, space, objects and interaction. Each category was investigated taking into consideration some aspects that could express the characteristics of the child’s behaviour related to them. In other words, these aspects represented a guide that questioned about the empirical indicators of each category, collected by researchers who observed the game context and aimed at learning about the children that took part in the research. A total of 88 questionnaires were analysed.

For the present study, it was exclusively underlined the aspects related to the category “interaction”, which correspond to important data about social relation among our children. The questionnaire contained nineteen questions at this category, and they were about the following contents: 1) peer relation: acting friendly, choices of peers, how did sharing take part in the behaviour, possibility to work with different colleagues; 2) social attitudes: identification of the right time to talk and/or listen, what comments and contributions were made, if the child followed too much other opinions or could stick to his; 3) relation with adults: acting politely, required help and how often it occurred, autonomy to work alone before asking for interferences, demonstration of respect; 4) dealing with rules: if rules and limits were respected, acceptation of errors and mistakes, attention at playing a match.

1) Peer relation. In reference to the relation among colleagues, children face an immediate challenge that is getting to know each other, since they come from different schools. The groups are formed with various grades and they also do not have the same age, which makes it even more challenging. As one can imagine, the first meetings represent some anxiety for a child who does not feel familiar with such diversity and adults are very supportive with him/her, but at the same time, stimulate choices and short dialogues. Meanwhile, we observe what happens, how each one reacts and plays, with whom they sit and talk.

Another aspect that must be under observation is the will and/or capacity to share, because no one should bring personal belongings and some children find it very uncomfortable, for example, to have one eraser per table, to use the same coloured pencils another one is using or not to take home the game he/she played with. In the beginning, both, making new friends and sharing objects require many adjustments and they are mainly adult referenced. With interventions and significant experiences, children start changing attitudes, becoming more friendly, opened to accept differences among peers and able to share and play games with different opponents.

To sum up, it was possible to find out that the investigated aspects at relation with peers allowed adults to mediate, observe, suggest and establish rules. They also have put challenges that all children could deal with, taking into consideration both interventions and suggested activities.

2) Social attitudes. Taking social attitudes into consideration, every game situation requires from the players a few behaviour procedures, such as pay attention to the movements the opponents do, consider different points of view and know when the turn to play is. It is also most adequate to listen quietly to one who is talking and to add contribution to a conversation, instead of changing the subject. All this is achieved after more than one semester discussing frequently about what is expected and how annoying it is not to be heard or respected.

The main point is to experience negative moments and become conscious of them, not to reinforce but to aim at changing what does not work for one’s good and for the group harmony. Idea exchange in the game and intervention context also shows interesting progress due to the construction of personal opinion and the possibility of making a point about a problem-solving situation posed to the group, for example. In the beginning, children tend to copy a colleague’s opinion and find it very difficult to share a thought, explain a strategy or express themselves. With adult interference and support, they gradually became more confident to share a point of view and even to expose doubts and fears, willing to get some help from peers to achieve better results and new ideas to deal with school challenges. So, it was possible to find out that the investigated aspects at social attitudes allowed adults to discuss, inform about what was expected, stimulate self-control and good manners. They also have put challenges that all children could deal with, taking into consideration both, interventions and suggested activities.

3) Relation with adults. One issue for young people is to conquer a natural and sincere relationship with adults, in special the ones they use to admire and fear at the same time, such as teachers. To act politely and respectfully is an obligation but they seldom understand why it is so important to pay attention to some protocols the one-to-one relation demands. The game context favours to acknowledge this because during the period of time a match takes place, there is no hierarchy between adult and child, or among themselves: rules regulate actions and procedures. This fact allows a very significant discussion about the reason people follow social rules: they make relations more organized, so that everyone knows how to behave and react. It takes a long time until they agree that rules are made to make life simpler instead of boring.

Another fundamental aspect to be observed at the game context is how much and when a child asks for help or requires adult interference. Many children show lack of independence, demanding the teacher’s permanent presence in order to confirm decisions, say what to do, analyse what is right or wrong, correct mistakes, and even needs compliments to go ahead. Once again, playing games is an excellent opportunity to make children become more autonomous and less dependent from adult company, especially because a match supposes individual players and many times they have to compete using their best resources or build up strategies they would not want to share before the game is over.

To sum up, it was possible to find out that the investigated aspects at relation with adults enabled them to build up a harmonic relationship, also mediated by rules. The challenges were adequate and favoured children to consider interventions and find solutions to the problem-solving situations.

4) Dealing with rules. Rules and limits represent a big deal to children who have behaviour difficulties and/or social inadequacy. The game context demands constant respect and consideration of rules, but it takes some time for them to understand and become able to do so. This is a powerful and significant situation, because every child wants to participate, and to follow the rules is an imperial condition which he/she is willing to admit. In the beginning, there are many quarrels caused by the constant disruption some players provoke. They find it difficult not only to follow the rules, but also to accept errors, as they rarely admit it was a personal mistake that has led to loosing a match, and this fact is one of the most frequent reasons for inadequacies. When this situation happens and there is adult intervention, helping them comprehend the parts and the whole, they gradually become able to realise how necessary it is to follow the rules, to learn from opponents, to pay attention to what it going on and search for inner resources that show them what can be done in order to make better decisions and win. As a conclusion, it was possible to find out that the investigated aspects at dealing with rules became an interesting opportunity to allow adults to discuss about consequences and stimulate the construction of inner resources to consider rules as social mediators. They also have put challenges and interventions that all children could deal with, achieving good results.

These four contents of the interaction category represent the characteristics of child social behaviour investigated at the research. They give at least two important information: firstly, they show the contribution of playing games as an interesting context to make children behave more adequately, and they also indicate in which subjects they need more help to change.

2. Results

After the period of three semesters, important information was collected and many changes were observed at the game context due to social development. It is necessary to mention that along this period, children were seen at the laboratory for one hour every week and there were continuous game activities, adult intervention and attention to each child’s demands.

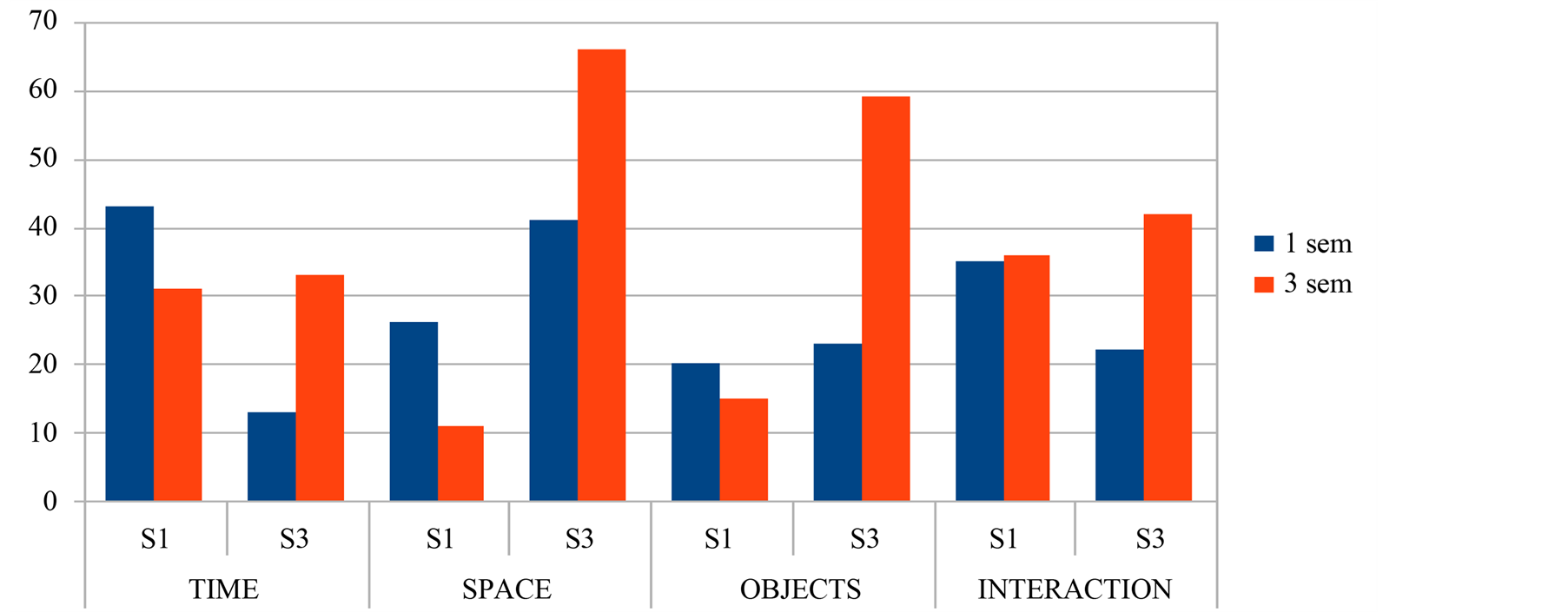

Taking the questionnaire into consideration to analyze data, three scores were defined in order to register children’s procedures and attitudes: 3 for high, 2 for medium or 1 for low, to each aspect of every category, according to the frequency observed. Researchers summed up the total of scores in each semester and compared them, aiming at verifying if the game context interfered in favour of attitude improvement, and in which categories it occurred high scores. Results showed that interaction, among the other categories (time, space and objects), was the last achievement to be beneficiated by the interventions in the game context, although all investigated categories increased scores. Figure 1 indicates the changes, comparing scores 1 (S1) and 3 (S3) at each category, considering the first and third semesters.

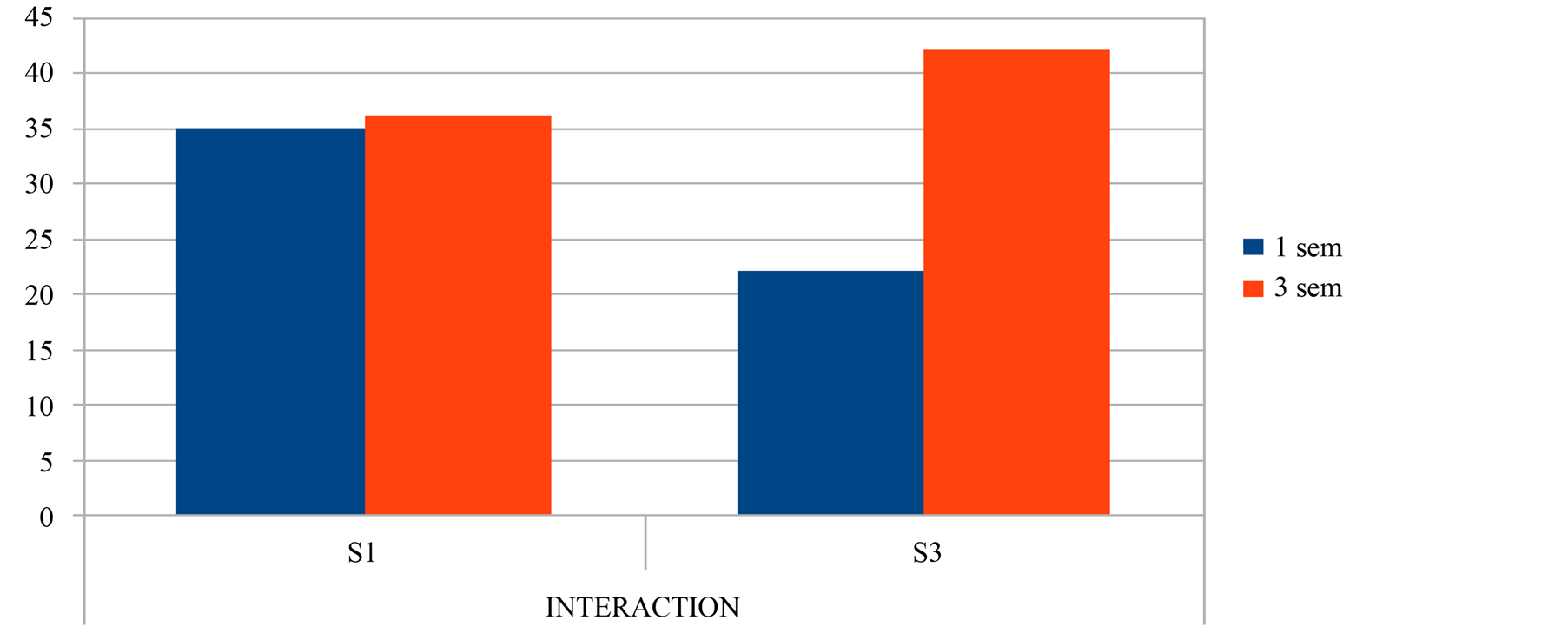

Changes at interaction were more discrete, when compared with the other three categories, showing only 20% high score (S3) increase, considering the first with the third semester, as indicated at Figure 2.

Researchers understand that this result is not a surprise, considering the piagetian based perspective on child development. That is to say, firstly one has to explore and get to know objects and its characteristics, conceiving them in space, time and organizing sequence of actions. After that, he/she gradually becomes capable and more interested to invest in relationships, meaning: intentionally interact with others and consider social demands as something possible to accept and understood as a social regulator. To do so, the child goes through a process that starts from a very self-centered reference and grows to a more open and socialized one. This descentration process takes a few years, and we were able to observe that the children we work with at the laboratory showed much difficulty in being able to share, respect limits and rules, and also interact cooperatively.

Figure 1. Distribution of scores 1 and 3 per category in 1st and 3rd semesters.

Figure 2. Distribution of score 3 (S3) at interaction in 1st and 3rd semesters.

Nevertheless, after three semesters participating at the intervention program, it was possible to identify relevantprogresses in children’s attitudes, as results seemed to show. Among the four contents of the interaction category (peer relation, social attitudes, relation with adults and dealing with rules), many differences were observed. Children acted more friendly and accepted different partners to work; were able to listen and contribute with comments; acted more politely with adults and only asked for help after trying to solve a challenge; showed more flexibility to deal with mistakes and find solutions according to the rules. In addition, they became able to take other points of view into consideration, listened more carefully to different opinions, shared information with better argumentation, respected rules with less need of adult interference and showed more autonomous behaviour.

3. Discussion and Conclusion

By the end of this research it was possible to confirm that playing games in an intervention context stimulated positive changes, not only at “interaction” category, as mentioned before, but also at “objects”, “space” and “time”, that is to say, children showed progress to deal with objects, improve spatial organization and enhance awareness with time demands. It also influenced in favour of attitude change, making them aim at building up new social behaviour patterns. As a consequence, it enabled all participants to interact and establish a better quality of relation, based on cooperation and mutual respect.

To take part on this project, with games and problem-solving situations, a powerful benefit was brought up, because the new conquers became one’s possession and could be transferred to other environments, such as at home and school. In other words, the changes in behaviour and attitudes were not reduced to the immediate results observed at the laboratory: they not only interfered positively in the moment children were playing games, but also contributed to social development in general. This precious information was taken from informal interviews, made with parents and teachers, while discussing about what could be noticed. It was a consensus among them that after the three semester term program was over children behaved differently. This consequence is considerably important and opens a new field for further investigation!

References

- Caillois, R. (1958). Os jogos e os homens—a máscara e a vertigem (Games and mankind—mask and vertigo). Lisboa: Cotovia. (in Portuguese)

- Chateau, J. (1955). O jogo e a crianca (Games and the child). Sao Paulo: Summus. (in Portuguese)

- De Macedo, L., Petty, A. L., & Passos, N. C. (1997). 4 Cores, Senha e Domino: Oficinas de jogos em uma Perspectiva Construtivista e Psicopedagogica (4 Colors, Mastermind and Domino: Game-Workshops in a Constructivist and Psychopedagogical Perspective). Sao Paulo: Casa do Psicologo. (in Portuguese)

- De Macedo, L., Petty, A. L., & Passos, N. C. (2000). Aprender com Jogos e Situacoes-Problema (Learning with Games and Problem-Solving Situations). Porto Alegre: Artmed. (in Portuguese)

- De Macedo, L., Petty, A. L., & Passos, N. C. (2005). Os Jogos e o Lúdico na Aprendizagem Escolar (Games and the Ludic Aspect in School Learning). Porto Alegre: Artmed. (in Portuguese)

- De Souza, M.T.C. Coelho; Petty, A.L. et al. (2002). Assessing Game Activities: A Study with Brazilian Children. In J. Retschitzki, & R. Haddad-Zubel, (Eds.), Step by Step. Suisse: Editions Universitaires Fribourg.

- Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo Ludens—o jogo como elemento da cultura (Homo Ludens—The Cultural Influence). Sao Paulo: Perspectiva. (in Portuguese)

- Petty, A. L., & De Souza, M. T. C. (2012). Executive Functions Development and Playing Games. US-China Education Review B, 9, 795-801.

- Piaget, J. (1932). Le jugement moral chez l’enfant. Paris: P.U.F. (in French)

- Piaget, J. (1945). Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood. New York: Norton Library.