Advances in Journalism and Communication

Vol.2 No.3(2014), Article ID:48021,15 pages

DOI:10.4236/ajc.2014.23008

Study on the Classification of Speech Anxiety Using Q-Methodology Analysis

SeoYoung Lee

GSI, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

Email: leeseoyoungann1004@gmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 23 May 2014; revised 28 June 2014; accepted 20 July 2014

Abstract

Public speaking is one of the cornerstones of mass communication, the influence of which has only been enhanced with the advent of the modern era. Yet despite its importance, up to 40% of the world’s population feels anxious when faced with the prospect of presenting in front of an audience (Wilbur, 1981). However, public speaking anxiety is human condition that can be understood and with effort, overcome by sufferers. Based on theoretical research, this study presents an empirical investigation of speech anxiety. The research uses Q-methodology to generate categories of speakers and then draws on the PQ-method program to suggest ways for speakers to improve their speaking confidence based on these categories. This research is of a value to those who are interested in speech anxiety for therapeutic or pedagogical practice.

Keywords:Communication Apprehension, Trait Anxiety, State Anxiety, Anxious Arousal, Public Speaking, Q-Method, Stage Fright

1. Introduction

As society becomes more pluralistic, our social lives become more complicated which heightens the need for effective oratory skills.

This study provides a method of categorizing people according to their propensity to speech anxiety. It also aims to analyze the differences between each category in the factors of speech anxiety with the aim of deriving a typology of the components of the condition.

This study uses speech communication theory to derive practical solutions for dealing with speech anxiety. Effective communication is paramount in today’s world where modern technologies offer numerous means for the exchanging of ideas and information. But verbal communication still remains the most important mode of human interaction. For example a professor’s performance is evaluated not only by the content of his/her lecture but also by his/her speech delivery. The professor needs to be able to articulate clearly and in an inspiring manner as well.

In a pluralistic world where our social lives become ever more complex, the need for verbal communication of ideas and information remains vitally important. Yet 40% of the world’s population feels some sort of anxiety about public speaking (Wilbur, 1981). Borkovec and O’Brien (1976) report that 25% of the adult population feels anxious about public speaking.

Most people have reported some feelings of public speaking anxiety. A wide body of academic literature attributes the causes of this condition to state or trait anxiety or a combination of the two. Based on my own theoretical research and teachings as a professor of speech communication as well as my experience in broadcasting, the researcher suggests using Q-methodology as instructional techniques to assist speakers in overcoming their anxiety.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Speech Anxiety

It was Spielberger (1966) who first suggested that anxiety is caused by a combination of the genetic disposition of a person (trait) and his emotional and mental state at a particular time. Spielberger’s concept is applicable to a variety of situations and not just public speaking (Ayres & Hopf, 1993; Beatty, 1988; Beatty & Clair, 1990; McCroskey, 1997; McCroskey & Beatty, 1986) all sort to confirm that trait and state could explain why some people had such an aversion to public speaking.

When people are faced with a stressful situation, it has an impact on them physiologically, cognitively and behaviorally (Lang 1986). Fear or anxiety causes a number of physiological reactions such as increased heart rate, sweaty palms, numbness etc. Such autonomous reactions have been observed in speaking situations (Beatty & Dobos, 1997).

2.2. Trait Anxiety

Trait anxiety is a person’s genetic predisposition to feeling anxious when faced with an uncomfortable or life threatening situations—such as the fear of being ridiculed in front of an audience. Beatty and McCroskey (2000) found that a person’s communication apprehension is 80% genetically determined.

According to the Trait-State theory, highly anxious trait people are likely to experience heightened levels of state-anxiety, more seriously and more frequently, when faced with threats to self esteem (Spielberger, 1966).

Trait anxiety may also affect how a speaker interprets the non verbal responses of an audience (Hsu, 2009). Anxious individuals tend to have more negative opinions of their speech and will blame it on the audience. Less anxious individuals tend to view their own performances positively.

2.3. State Anxiety

State-anxiety contributes up to 20% of a person’s adverse reaction. Trait anxiety is a good indicator of a person’s state anxiety. State-anxiety can be decomposed into a person’s reactivity—or the magnitude of his/or response to a stimuli plus his or her situation (Harris, Sawyer, & Behnke, 2006). The situation of a speech performance can be just as powerful as trait anxiety, if not more, in predicting state anxiety (Ayres, 1990; Beatty & Friedland, 1990; Harris, Sawyer, & Behnke, 2006; Keaten, Kelly, & Finch, 2004).

Klonowicz, Zawadzka, Zawadzki (1987) found that highly-reactive persons have elevated arousal levels even in the absence of stimuli. Thus they are likely to have a greater reaction to events around them. When aroused, they are likely to have a negative reaction to the stimuli. It is a cognitive process (Beatty, 1988) where the reaction to an arousal is viewed adversely. This psychological reaction only compounds the anxiety beyond the levels predicted by trait-anxiety. Conversely low reactive people may be aroused but are less likely to descend into anxiety.

Behnke & Sawyer (2001b) suggests that psychologically reactive people could benefit from public speaking practice sessions full of stress but with likelihood of a successful performance. Others like Beatty & McCroskey (2000) contend that it is difficult to utilize therapy to reduce psychological anxiety because so much of speech anxiety is genetically determined. Beatty and Valence (2000) showed that attempts to make classroom speeches less stressful did not prove effective. Still others like Kelly and Keaten (2000) suggest pedagogical means may provide effective cures.

Based on an experiment using bursting balloons to emulate stress, Behnke & Sawyer (2001b) found that psychological state anxiety reactivity contributed up to an additional 23% more state anxiety than the levels predicted by trait anxiety.

A speaker’s anxiety is also affected by the situation in which he is asked to perform (Beatty, 1998). If the speaker is unfamiliar with the audience of the environment, he or she is more likely to be anxious, though the impact of familiarity is weak. This suggests that becoming accustomed to a speaking environment may not reduce speech anxiety. A speaker is also anxious if faced with speaking to superiors.

2.4. Behaviour Inhibition System

Anxiety is generated by our brain’s Behaviour Inhibition System (BIS) (Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Gray, 1982). These neurological circuits are activated by situations such as public speaking where events are deviating from expectations and there is the possibility of punishment, non-reward or fear. This results in increased sensitivity to surroundings, speech disfluency, rigidity, heightened arousal, agitation and inhibited behavior. Those individuals with high trait anxiety disposition are particularly prone to a BIS reaction (Gray, 1982) and thus are more vulnerable to anxiety. This physiological reaction is the root cause of speech anxiety (Beatty, McCroskey, & Heisel, 1998).

2.5. The Four Stages of Speaker Apprehension

There are four stages of public speaker anxiety (Behnke & Sawyer, 2001a; Osorio, Crippa, & Loureiro, 2008). Stage 1 is the anticipatory stage when the speaker knows that the impending moment is imminent. This is followed by confrontational anxiety in the first few minutes of the speech. Anxiety adaptation occurs during the last minute of the speech and anxiety release after the speech is completed. Psychological anxiety peaks at the anticipatory stage while physiological anxiety peaks at the confrontational stage (Behnke & Sawyer, 2001a). After anxiety peaks, the speaker is more likely to adapt to the situation enabling speech anxiety to ease. The observation that state anxiety will ease with continuous exposure to fearful situation is known as Habituation (Finn, Sawyer, & Behnke, 2003; Gray, 1982, 1990; Gray & McNaughton, 2000). As habituation creeps in, the brain’s BIS circuits will cease to exert influence over behaviour.

2.6. Q-Methodology

Q-Methodology is a research method used in psychology and in social sciences to study people’s “subjectivity”—that is, their viewpoint. Q was developed by psychologist William Stephenson. It has been used both in clinical settings for assessing a patient’s progress over time (intra-rater comparison) as well as in research settings that examines how people think about a topic (inter-rater comparisons).

Statistically, the variables of “R-research” are items or stimuli, whereas the variables of Q-methodology are people (Brown, 1980). The name “Q” comes from the form of factor analysis that is used to analyze the data. Normal factor analysis, called “R method”, involves finding correlations between variables (e.g., height and age) across a sample of subjects. Q, on the other hand, looks for correlations between subjects across a sample of variables.

Q-factor analysis reduces the many individual viewpoints of the subjects down to a few “factors”, which are claimed to represent shared ways of thinking. It is sometimes said that Q-factor analysis is R factor analysis with the data table turned sideways. While helpful as a heuristic for understanding Q, this explanation may be misleading, as most Q-methodologists argue that for mathematical reasons no one data matrix would be suitable for analysis with both Q and R.

2.6.1. Sorting the Statements in a Q-Sort

The data for Q-factor analysis come from a series of “Q-sorts” performed by one or more subjects. A Q-sort is a ranking of variables—typically presented as statements printed on small cards—according to some “condition of instruction”. For example, in a Q study of people’s views of a celebrity, a subject might be given statements like “He is a deeply religious man” and “He is a liar”, and asked to sort them from “most like how I think about this celebrity” to “least like how I think about this celebrity”. The use of ranking, rather than asking subjects to rate their agreement with statements individually, is meant to capture the idea that people think about ideas in relation to other ideas, rather than in isolation.

The sample of statements for a Q-sort is drawn from and claimed to be representative of a “concourse”—the sum of all things people say or think about the issue being investigated. Since concourses do not have clear membership lists (as would be the case in the population of subjects), statements cannot be drawn randomly so they do not meet R methodology expectations for statistically valid inferences. Commonly Q-methodologists use a structured sampling approach in order to try and represent the full breadth of the concourse.

One salient difference between Q and other social science research methodologies, such as surveys, is that it typically uses fewer subjects. This can be a strength, as Q is sometimes used with a single subject, and it makes research far less expensive. In such cases, a person will rank the same set of statements under different conditions of instruction. For example, someone might be given a set of statements about personality traits and then asked to rank them according to how well they describe herself, her ideal self, her father, her mother, etc. Working with a single individual is particularly relevant in the study of how an individual's rankings change over time and this was the first use of Q-methodology.

In studies of intelligence, Q-factor analysis can generate Consensus Based Assessment (CBA) scores as direct measures. Alternatively, the unit of measurement of a person in this context is his factor loading for a Q-sort he or she performs. Factors represent norms with respect to schemata. The individual who gains the highest factor loading on an operant factor is the person most able to conceive the norm for the factor. What the norm means is a matter, always, for conjecture and refutation (Popper, 1959). It may be indicative of the wisest solution, or the most responsible, the most important, or an optimized-balanced solution. These are all matters for future determination.

An alternative method that determines the similarity among subjects somewhat like Q-methodology, as well as the cultural ‘truth” of the statements used in the test, is Cultural Consensus Theory.

The “Q-sort” data collection procedure is traditionally done using a paper template and the sample of statements or other stimuli printed on individual cards. However, there are also computer software applications for conducting online Q-sorts. For example, consulting firm Davis Brand Capital has created a proprietary online product, nQue, which is used to conduct online Q-sorts that mimic the analog, paper-based sorting procedure. However, the web-based software application that uses a drag-and-drop, graphical user interface to assist researchers is not available for commercial sale (Brown, 1980).

2.6.2. P-Samples

Stephenson (1953) said Q-methodology is based on small sample doctrine because large P-samples may cause statistical problems. Q-methodology trait is not jumping the logic or guessing. It has an experience based abduction trait (Plummar, 1974; Wells, 1975).

Participant selection in Q-methodology is not based on probability sampling (Aman, 2000) because the sampling is of the Q-set, not the participants (Stainton, Rogers, 1993). A large number of participants sometimes referred to as the P-set (van Excel, De Grand, 2005) are not required in Q-methodology as the aim of the process is to extricate key opinions of a selected participant group (Watts; Skenner, 2005). Accordingly, single cases came be the focus of Q-methodology research (Brown, 1993).

The reliability of each factor or cluster of beliefs is enhanced when 4 - 5 participants make up each factor. There are usually no more than 7 factors identified in a Q-sort (Brown, 1993). Accordingly, breadth and diversity of viewpoints is best achieved when a participant group contains between 40 - 80 participants (Stainton & Rogers, 2005). However reliable results can be obtained with far fewer participants (Watts and Stenner, 2006).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

A speaker’s subjective experience of speech anxiety is amenable to Q-methodology and classification. Based on a speaker’s subjective point of view, the traits of speakers who are susceptible to speech anxiety are classified according to their values, attitudes, assessment and orientation.

Research question 1: How to categorize people according to their speech anxiety and what are the characteristics of each classification?

Research question 2: What are the differences between the categories of speech anxiety?

Participants—P-Sample The study sample consists of 20 graduates from the school of politics majoring in social science. Q studies can be very effective for studying small samples. Q studies are cost effective and take less time than an interview.

The most common participant to Q-sample ratio items found in other Q studies was roughly 1 to 1 (Watts & Stenner, 2005). Therefore the number of participants should roughly match the number of Q-sample items.

3.2. Research, Design and Analysis

Q-samples are extracted from a concourse. Q-samples are respondents of a Q-sort and P-samples. The most important aim is how to structure the Q-samples. Respondents are usually interviewed to gain a deep understanding of their mindset. In this study P-samples are students of speech communication of which a subset of 20 interviewees were chosen. Each P-sample is normally distributed. We examine each sample to see the kind of classifications showing. The respondents are 20 graduate students majoring in social science (Table 1).

Interviews are referred to Q-sort. This data is analyzed by the Q-method program (Table 2).

The sort requires the use of software to analyze the data such as PQ-method. Interview participants score each statement in the survey. Correlations are then calculated between sorts to generate a correlation matrix.

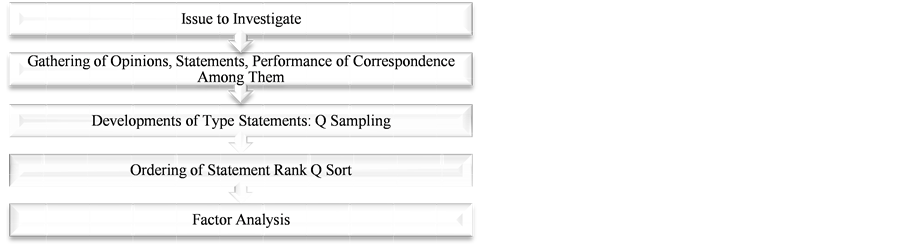

Factors are then extracted from this correlation matrix. Factor analysis can then be either centroid factor analysis or principal components analysis. There is no conclusive evidence that one method is better than the other. Both methods produce similar results (Watts & Stener, 2005) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Distribution and numbers of statements.

Table 2. Q statements of interviewees and descending array of z scores.

Figure 1. Stages of Q-factor analysis.

4. Research Results

4.1. Q-Factor Analysis

Type 1: Naturally Eloquent Speakers

Type 1 people are naturally eloquent speakers. They like to speak in front of an audience and they believe that it is an innate talent. They tend to think that their ability will always be available so they rarely feel anxious when speaking publicly nor do they care about a lack of experience. These are the traits of an innate naturally eloquent speaker. In addition they enjoy speaking in front of an audience but they tend not to make an effort. However their speech ability could be enhanced by practice and environmental factors so a lack of effort is a detriment. Yet compared to a type 2, type 1 persons are more anxious when making a speech (Table 3).

Type 2: Developed Professional Speakers

Type 2 people are professional speakers. They are developed speech professionals such as announcers, MCs and broadcasters. They like to speak in front of audiences, their speech is natural and their eye contact is natural. They are negative on speech anxiety, introverted characteristics, and the innate talent variables, so they are typically well trained in speech. Hence the name, developed speech professionals. Compared, to type 3 speakers, type 2 people conspicuously enjoy speaking in front of an audience. In addition, nonverbal messages, voice tone and body language are well executed so there is a big difference between type 2 and 3. Also compared with type 4, type 2 speakers deliver their speech naturally as well as nonverbal messages, voice tone and body language. Therefore there is also a marked difference between type 2 and 4 (Table 4).

Type 3: Introverted Speech Anxious Speakers

Type 3 persons are introverted with a high speech anxiety. They tend to believe that if they have more experience that they will improve. They are untrained speakers which is the greatest source of their anxiety. They are negative on the enjoyment for speaking in front audiences, voice tone, nonverbal expression, gestures, and the eye contact variables. They have an introverted personality so they are more concerned about their relative lack of experience. But when they are given more opportunities to speak in front of audiences they feel confident about improvement. When compared to type 4, a type 3 person experiences speech and presentation anxiety as an innate trait. This trait anxiety is typical of type 3 speakers. To overcome this, type 3 speakers need to improve their breath control. Such trait anxiety comes from timidity, shyness and sensitivity which emphasizes the importance of mind control and letting go of perfectionism. Other important ways to mitigate such anxiety include, using relaxation techniques and practicing positive thinking (Table 5).

Type 4: Speakers with Situational Stage Fright

The most prominent feature of type 4 speakers is they experience speech anxiety when they have speak in public as opposed to a one to one interaction in which they have no issues. They are positive on public speech anxiety, but are awkward when using gestures. In addition, they are negative on, a lack of confidence, experiencing psychological anxiety in formal situations, anxiety due to presentation skills, use of nonverbal communication, and the anxiety about making speeches variables. This type suffers from situational anxiety when they make a speech in public rather than anxiety over giving a speech itself. Situational anxiety sufferers can overcome their fears with experience and practice which leads to situational familiarity and increased confidence. Practice and experience clearly makes a significant difference to the skill levels of the practitioner. For example, Steve Jobs prepared 55 hours for a single presentation, so this type of person needs plenty of preparation to overcome this kind of anxiety (Table 6).

Table 3. Descending array of z scores and item description for type 1 (above and below +/−1).

Table 4. Descending array of z scores and item description for type 2 (above and below +/−1).

Table 5. Descending array of z scores and item description for type 3 (above and below +/−1).

Table 6. Descending array of z scores and item description for type 4 (above and below +/−1).

4.2. Comparison Analysis between the Main Types

Comparison between type 1 and type 2 speakers

Table 7 shows differences and similarities between the type 1 and type 2 speakers. Marked differences in attitudes are demonstrated in question 24 and 25. Statement 1 and 6 also showed some notable differences in attitudes. The results showed that professional speakers are more confident and like to speak in public while the results for type 1 speakers reflect some hesitancy and anxiety though not in all aspects of communication apprehension.

Comparison between type 1 and type 3 speakers

Table 8 shows differences in attitudes between naturally eloquent speakers (type 1) and introverted speech anxious types (type 3). When compared to type 1 speakers, type 3 speakers displayed larger differences in their

Table 8. Descending array of differences between factors type 1 and type 3.

public speaking attitudes than that was shown for type 2 speakers in Table2 As expected, type 3 speakers showed less confidence in their public speaking ability compared to type 1 speakers—as reflected in statements 2, 21, 16, 8, 13 & 23.

Comparison between type 1 and type 4 speakers

Type 4 speakers are confident speaking person to person but not in public and this attitude is reflected in the positive score (1.452) shown for statement 11. Interesting to note however that type 1 speakers are negative on this aspect. As expected, type 4 speakers are not confident in doing presentations (statement 8). Statements 10, 14 and 2 all reflect notable difference in ability attitudes between type 1 and 4 speakers (Table 9).

Comparison between type 2 and 3 speakers

There are more notable differences in attitudes between these two types of speakers than in the three previous tables. Statement 23, 2, 21 and 10 all reflect the differences that we would expect between the two speaker types. It is interesting to note that type 3 speakers still felt a moderate level of ability in their public speaking ability (statement 14) (Table 10).

Comparison between the type 2 and type 4 speakers

Similar to the previous table, there are numerous differences in the attitudes, confidence and abilities between type 2 and type 4 speakers. Again, it is interesting to note is that type 4 speakers don’t feel anxious (statement 6). The biggest differences (statement 10, 14, 6, 8, 12, 24 and 25) are all in line with what we would expect between these groups of people (Table 11).

Comparison between type 3 and type 4 speakers

Type 3 and type 4 speakers are the two groups with the least confidence in their public speaking ability. But the following table shows that type 3 speakers are considerably less confident than type 4 speakers about their speech making abilities–as reflected in statement 23, 24, 6, 16, 21, 3, and 2. Once more, it is interesting to note that both groups don’t feel nervous about making a speech (statement 1) but they admit to feeling speech anxiety (statement 8). In addition, the groups don’t feel confident about their non-verbal communication skills (statement 10) (Table 12).

Table 9. Descending array of differences between factors type 1 and type 4.

Table 10. Descending array of differences between factors type 2 and type 3.

Table 11. Descending array of differences between factors type 2 and type 4.

Table 12. Descending array of differences between factors type 3 and type 4.

5. Discussion

This paper derived methods to overcome speech anxiety by analyzing the personal traits of speakers, the characteristics of communication apprehension, a speaker’s self perception and their public speaking experience. A person’s speech ability depends on how fast they can overcome their speech anxiety. The speaker has to come to terms with their speech apprehension and alter their speech style. From an academic perspective, there is a plethora of research on this discipline but this paper is the first to use Q-methodology to examine the problem. The classification of speech anxiety has pragmatic value.

Recent research indicates that “speaking in from of others is rated as the largest cause of anxiety in people” (Anwan, Azher, Anwar, & Naz, 2010).

Current research suggests three techniques to reduce public speaking anxiety. First, systematic desensitization involves relaxation, deep breathing, and visualization (Friedrich, Goss, Cunconan, & Lane, 1997). This technique can be practiced in group settings or alone.

Second, cognitive restructuring requires participants to create a negative self-talk list, identify irrational beliefs embedded in each thought, develop a coping statement for each irrational belief, and practice the coping statements until they become second nature (Ayres, Hopf, & Peterson, 2000).

The third technique, skills training, refers to learning and practicing techniques targeted toward improving individual speaking behaviours (Kelly, 1997). Skill training usually involves participating in a course where the student learns and practices public speaking skills.

Berkun (2009) suggests being prepared by practicing will assist in overcoming speech anxiety. Memorize key points but don’t recite the speech word for word like a robot. Visualisation techniques such as imagining standing in front of an audience will prepare a speaker to deal with the adverse situation. Perfecting your presentation through practice will also provide you with confidence and a mental picture of how to proceed throughout different points of the speech. It also makes it easier to improvise should the audience behave badly like falling asleep or if someone heckles you.

Other strategies recommended by Berkun for calming nerves include: arriving early to avoid being flustered, checking the sound and audio visual equipment to avoid hiccups, pacing up and down the stage whilst speaking helps to calm nerves, sitting with the audience beforehand to obtain a feel of what they are seeing and eat early but not before your talk. Speaking with members of the audience beforehand puts your mind in the mood for talking–similar to overcoming the initial nerves of talking to strangers when arriving at a party.

Some people find that exercise will burn off their nervous energy before a talk. They then become too tired to worry about nerves. Exercise also puts you in a natural high so you will be more relaxed on stage.

Anxious people will also need to deal with irrational thoughts such as being laughed at, saying something silly or putting people to sleep. Berkun (2009) believes that if you are comfortable talking to people in a social situation, then you should be comfortable talking to an audience. A speaker should apply this logic when dealing with this irrational thought. Most audiences are polite and will not judge you badly if you make an embarrassing mistake. President George Bush was infamous for making silly statements on camera and the media would ridicule him. But despite these verbal transgressions, he managed to be re-elected for a second term. Compare your irrationality to the verbal mistakes Bush committed during his presidency and you realize how irrelevant your worries are.

6. Conclusion

Using Q-methodology, I have categorized four types of people according to their speech anxiety. Type 1 persons are eloquent natural speakers. They enjoy speaking in front of an audience and they don’t believe that practicing will improve their natural ability. However, I find that naturally gifted speakers could improve their skills by practicing.

Type 2 persons are professional speakers such as broadcasters who have gotten accustomed to speaking publicly by constantly practicing in front of a camera or in front of an audience.

Type 3 persons are introverted person. They are genetically predisposed to trait-anxiety. They would benefit from systematic desensitization, positive thinking and relaxation therapy to mitigate their fear of public speaking. The treatment would involve continual exposure to a series of situations which cause anxiety (like giving a speech). In addition, the patient would be attempting to relax via deep muscle relaxation exercises. The initial stimuli do not provoke a lot of anxiety but gradually increased throughout the therapy session. Thus the introvert is trained to relax whilst being exposed to anxious stimuli. In this manner the bond between these stimuli and the anxiety responses will be weakened (Wolpe, 1958: p. 71).

There are other desensitization techniques such as reactive inhibition therapy which involves teaching introverts to deliberately evoke all the unpleasant feelings associated with speech anxiety (Malleson, 1959: p. 226). The basis of this therapy is that a person is always trying to escape from these unpleasant feelings but if he was made to face his fears, the cycle of anxiety would be broken.

Type 4 is situational fright person. They suffer from speech anxiety because of the lack of experience. It is a psychological condition triggered by the situation. Such speakers would benefit from exercising mind control—such as imagining that they are communicating in a one to one situation instead being in front of an audience. These people will improve their skills if they practice very hard.

Therefore I recommend cognitive behaviour therapy involving systematic desensitization and cognitive restructuring procedures as effective means for reducing worry and emotional responses in anxious situations. Constant practice and skills training will enable speech anxiety sufferers to overcome their fears. I also suggest using instructional techniques to improve the speaking confidence of speech anxiety sufferers for pedagogical and therapeutic practice.

References

- Anwan, R., Azher, M., Anwar, M. N., & Naz, A. (2010). An Investigation of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety and Its Relationship with Students’ Achievement. Journal of College Teaching and Learning, 7, 33-40.

- Ayres, J., & Hopf, T. (1993). Coping with Speech Anxiety. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Ayres, J., Hopf, T. S., & Peterson, E. (2000). A Test of Communication-Orientation Motivation (COM) Therapy. Communication Reports, 13, 35-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08934210009367721

- Beatty, M. J. (1988). Public Speaking Apprehension, Decision-Making Errors in the Selection of Speech Introduction Strategies and Adherence to Strategy. Communication Education, 37, 297-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634528809378731

- Beatty, M. J., & Dobos, J. A. (1997). Physiological Assessment. In J. A. Day, J. C. McCroskey, H. Ayres, T. Hopf, & D. M. Ayres (Eds.), Avoiding Communication Shyness, Reticience and Communication (2nd ed., pp. 216-230). Creskill, NJ. Hampton Press.

- Beatty, M., & Friedland, M. (1990). Public Speaking State Anxiety as a Function of Selected Situational and Predispositional Variables. Communication Education, 39, 142-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634529009378796

- Beatty, M. J., & Clair, R. P. (1990). Decision Rule Orientation and Public Speaking Apprehension. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 5, 105-116.

- Beatty, M. J., & Dobos, J. A. (1997). Psychological Assessment. In J. A. Daly, J. C. McCroskey, H. Ayres, T. Hopf, & D. M. Ayres (Eds.), Avoiding Communication Shyness, Reticence and Communication Apprehension (pp. 217-229). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Beatty, M. J., McCroskey, J. C., & Heisel, A. D. (1998). Communication Apprehension as Temperamental Expression: A Communibiological Paradigm. Communication Monographs, 65, 197-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03637759809376448

- Beatty, M. J., & McCroskey, J. C. (2000). The Communibiological Perspective: Implications for Communication in Instruction. Communication Education, 49, 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634520009379187

- Behnke R., & Sawyer, C. R. (2001a). Patterns Of Psychological State Anxiety in Public Speaking as a Function of Anxiety Sensitivity. Communication Quarterly, 49, 84-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463370109385616

- Behnke R., & Sawyer, C. R. (2001b). Public Speaking Arousal as a Function of Anticipatory Activation and Autonomic Reactivity. Communication Reports, 14, 73-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08934210109367740

- Berkun, S. (2009). Confessions of a Public Speaker. California: O’Reilly Media Inc.

- Borkovec, T. D., & O’Brien, G. T. (1976). Methodological and Target Issues in Analogue Therapy Outcome Research. In Hersen, E. Eisler, & P. Miller (Eds.), Progrees in Behaviour Modification (p. 3). New York: Academic Press.

- Finn, A. N., Sawyer, C. R., & Behnke, R. (2003). Audience-Perceived Anxiety Patterns of Public Speakers. Communication Quarterly, 51, 470-481. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463370309370168

- Friedrich, G., Goss, B., Cunconan, T., & Lane, D. R. (1997). Systematic Desensitization. In Avoiding Communication: Shyness, Reticence, and Communication Apprehension (pp. 305-330). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Gray, J. A. (1982). The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo-Hippocampal System. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gray, J. A. (1990). Brain Systems that Mediate both Emotion and Cognition. Cognition & Emotion, 4, 269-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699939008410799

- Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (1982). The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An Enquiry into the Functions of the Septo-Hippocampal System (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (2000). Anxiolytic Action on the Behavioural Inhibition System Implies Multiple Types of Arousal Contribute to Anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61, 161-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00344-X

- Harris, K. B., Sawver, C., & Behnke, R. R. (2006). Predicting Speech State Anxiety from Trait Anxiety, Reactivity, and Situational Influences. Communication Quarterly, 54, 213-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463370600650936

- Hsu, C. F. (2009). The Relationship of Trait Anxiety, Audience Nonverbal Feedback and Attributions to Public Speaking State Anxiety. Communication Research Reports, 26, 237-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08824090903074407

- Kelly, L. (1997). Skills Training as a Treatment for Communication Problems. In J. A. Daly, J. C. McCroskey, H. A. Ayres, T. Hopf, & D. M. Ayres (Eds.), Avoiding Communication: Shyness, Reticence, and Communication Apprehension (2nd ed., pp. 331-336). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

- Kelly, L., & Keaten, J. A. (2000). Treating Communication Anxiety: Implications of the Commuibiological Paradigm. Communication Education, 49, 45-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634520009379192

- Kelly, L., Keaten, J. A., & Finch, C. (2004). Reticent and Non-Reticent College Students’ Preferred Communication Channels for Communicating with Faculty. Communication Research Reports, 21, 197-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08824090409359981

- Klonowicz, T., Zawadzka, G., & Zawadzki, B. (1987). Reactivity, Arousal, and Coping with Stress. Personality and Individual Differences, 8, 793-798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(87)90132-2

- Lang, P. J. (1986). The Cognitive Psychophysiology of Emotion: Fear and Anxiety. In A. H. Tuma, & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the Anxiety Disorders (pp. 130-179). Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum.

- McCroskey, J. C., & Beatty, M. J. (1986). Oral Communication Apprehension. In W. H. Jones, J. M. Cheek, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Shyness: Perspectives on Research and Treatment (pp. 279-293). New York: Plenum Press.

- McCroskey, J. C. (1997). Willingness to Communicate, Communication Apprehension, and Self Perceived Communication Competence: Conceptualizations and Perspectives. In J. A. Daly, J. C. McCroskey, J. Ayres, T. Hopf, & D. M. Sonadre (Eds.), Avoiding Communication: Shyness, Reticence, and Communication Apprehension (2nd ed.). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

- Malleson, N. (1959). Panic and Phobia: A Possible Method of Treatment. The Lancet, 273, 225-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90052-2

- Osorio, F., Crippa, J. A., & Loureiro, S. R. (2008). Experimental Models for the Evaluation of Speech and Public Speaking Anxiety: A Critical Review of the Designs Adopted. The Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis, 2, 97.

- Popper, K. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. English Edition, London: Hutchison & Co.

- Spielberger, C. D. (1966). Anxiety and Behavior. New York: Academic Press.

- Stephenson, T. D. (1985). Q-Methodology in Communication Science: An Introduction. Communication Quarterly, 33, 193-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463378509369598

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2005). Doing Q-Methodological Research: Theory, Method & Interpretation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2, 67-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088705qp022oa

- Wilbur, P. K. (1981). Stand up, Speak up, or Shut up: A Practical Guide to Public Speaking. New York: Dembner Books.

- Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.