Advances in Breast Cancer Research

Vol.2 No.1(2013), Article ID:27248,6 pages DOI:10.4236/abcr.2013.21001

Axillary “Exclusion”—A Successful Technique for Reducing Seroma Formation after Mastectomy and Axillary Dissection

1Southampton University Hospital, Southampton, UK

2Salisbury District Hospital, Salisbury, UK

Email: ndabbas@gmail.com

Received October 1, 2012; revised November 7, 2012; accepted November 16, 2012

Keywords: Breast Cancer; Lymphocele; Seroma; Mastectomy; Axilla

ABSTRACT

Introduction: A seroma is the commonest complication of breast cancer surgery, and although its consequences most often cause no more than discomfort and anxiety, more important sequelae include flap necrosis and wound breakdown. Infection developing within seroma increases morbidity and often results in the need for re-admission, re-imaging, drainage and antibiotic usage. Numerous methods to reduce post-mastectomy seroma formation have been tried with no consistent success. Methods: 24 consecutive patients undergoing mastectomy and axillary clearance were recruited before and after a departmental change in practice. At the point of skin closure, patients either underwent “axillary exclusion” or not. Total drain outputs were recorded by community district nursing staff for all patients. At the first post-operative visit, the presence and severity of seroma was recorded. Results: 24 patients were included (study group 14, control group 10). Age, size of tumour, and number of positive lymph nodes and laterality were comparable between groups. Mean drain output for the entire group was 471 ml (3 - 1030 ml) over 5.21 days. The control group had a drain output of 763.5 ml (95%CI 674.2 - 852.8) while the study group had a mean drainage of 262.2 ml (95%CI 161.9 - 362.5), a reduction of over 65%, p < 0.001. 15 (62.5%) out of 24 patients developed seroma. 42.9% of the study group and 90% of the control group developed seroma, p < 0.01. Conclusion: Seromas are a common complication following mastectomy and axillary clearance. Our technique of axillary exclusion has resulted in significantly reduced drainage volumes and fewer seromas.

1. Introduction

Seromas represent the most common complication of breast cancer surgery [1], the aetiology of which remains obscure. Many surgeons view seromas as a necessary evil rather than a serious complication.

The commonest consequences of post-operative fluid collections are patient discomfort and anxiety, however more important consequences that can arise as secondary complications include flap necrosis and wound breakdown. Infection developing within seroma increases morbidity and often results in the need for re-admission, reimaging, drainage and antibiotic usage [2-4].

The significance of post-operative seroma in breast surgery lies in its frequency. The incidence is thought to be somewhere between 25% - 60% for mastectomy and axillary clearance [5,6], but has been reported as high as 85% [7] depending on it’s definition and the techniques employed to detect them.

Theories of aetiology are important in determining the most likely surgical technique for prevention. Various techniques have been studied in an attempt to minimise post-mastectomy drainage volumes and the incidence of seroma. None however, have been found to be consistently successful and consequently none are used in common practice. If it is believed that the disrupted lymphatics in the axillary fossa are central to aetiology, it follows that obliterating this space will minimise fluid collection. We introduce a novel technique of axillary exclusion, and present results of a series of 24 patients.

2. Patients and Methods

Patients undergoing mastectomy and axillary (level II/III) clearance at Southampton General Hospital and Princess Anne Hospital, Southampton were examined into the study. Over the period March to July 2008, 24 patients operated on by a single surgeon were investigated prospectively, before and after a departmental change in technique. After mastectomy, at the point of skin closure, patients either underwent axillary “exclusion” or not.

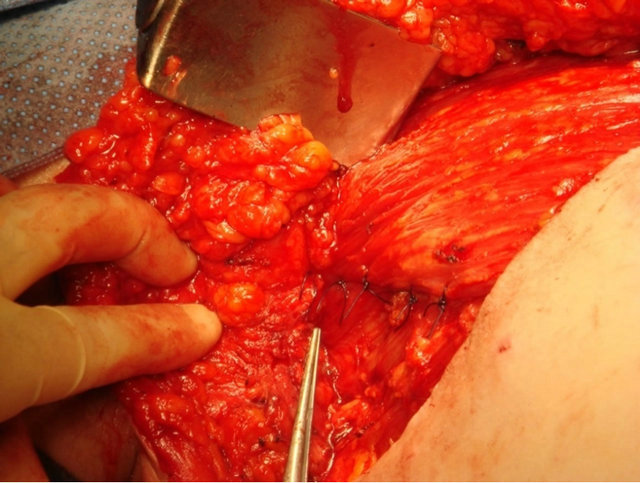

The technique involved suturing the superior mastectomy skin flap down to the free edge of pectoralis major and the lateral chest wall using a continuous 2/0 vicryl stitch (Figures 1(a)-(c)), and then placing 4 - 6 interrupted sutures between pectoralis major and minor to reliably exclude the axillary fossa from the remainder of the mastectomy cavity (Figure 1(d)).

A pressure dressing was applied to all wounds. 10F Handy Vacâ suction drains were placed at surgery in all patients with the tip placed within the mastectomy cavity, and total drain outputs were recorded by community district nursing staff for all patients prior to drain removal. Chi-squared analysis was used to determine difference between drain outputs in each group.

At the two-week first post-operative visit, the presence and severity of seroma was recorded. This was graded mild (asymptomatic), moderate (symptomatic but not requiring intervention, or severe (symptomaic requiring intervention). Unpaired t-test was used to determine significance in seroma incidence between groups.

3. Results

24 consecutive patients were included. Of these, the study group contained 14 and the control group 10

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c) (d)

(d)

Figure 1. Intra-operative photographs showing axillary exclusion technique: (a) Axillary fossa potential dead space after mastectomy and axillary clearance; (b) Suturing of superior mastectomy flap to pectoralis major; (c) Superior mastectomy flap sutured to free edge of pectoralis major and lateral chest wall; (d) Interrupted sutures to appose pectoralis major and minor, providing reliable axillary fossa exlusion.

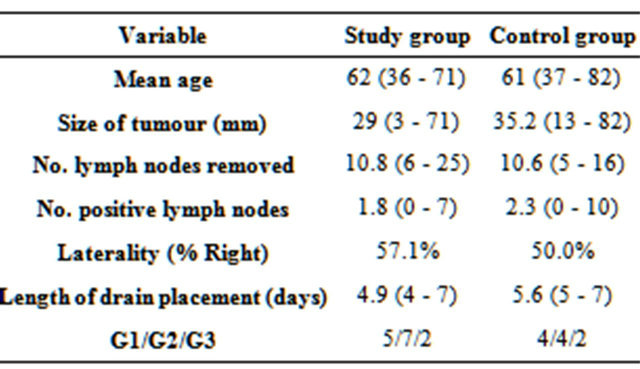

patients. Age, size of tumour, number of positive lymph nodes and laterality were comparable between groups (Table 1).

The median age of patients was 62 years (36 - 82 years). The laterality of operations was 10 (41.7%) left and 14 (58.3%) right. Types of pathology included invasive ductal carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ, and mixed invasive ductal/lobular carcinoma. 20 patients (83.3%) had invasive tumours (80% IDC, 20% mixed IDC/ILC). Sizes of tumour ranged from 3 - 82 mm (mean 29.8 mm).

Drains remained in situ for 4 - 7 days at the discretion of the community district nurse. At drain removal, total drain output was measured and recorded. Mean drain output for the entire group was 471 ml (range 3 - 1030 ml) over a mean of 5.21 days.

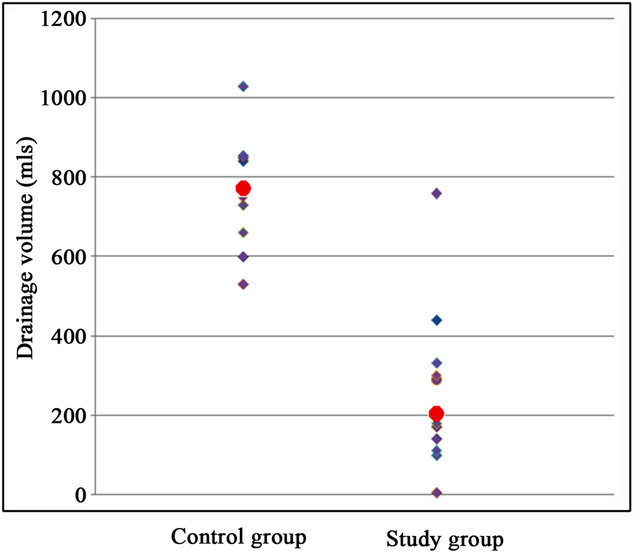

The control group had a drain output of 763.5 ml (95%CI 674.2 - 852.8) while the study group had a mean drainage of 262.2 ml (95%CI 161.9 - 362.5), a reduction of over 65%, p < 0.001 (Figures 2 and 3). 15 out of 24 patients developed seroma (rate 62.5%). 42.9% of the study group and 90.0% of the control group developed seroma. This difference is significant (p < 0.01). Seroma

Table 1. Comparison of results between study group and control group.

Figure 2. Drain outputs for control and study groups (red dots indicate median value).

Figure 3. Boxplot showing drain output volumes in study and control groups.

formation was not significantly related to number of lymph nodes obtained, nodal involvement, tumour size or grade.

4. Discussion

A seroma is an accumulation of serous fluid that develops following the formation of skin flaps during mastectomy or in the axillary dead space in the postoperative period [8]. The most likely cause for the formation of seroma is the disruption of lymphatic channels in the axilla [9-11]. However, laboratory studies have shown conflicting evidence, some determining the fluid to be lymph-like in quality [2,12], and others showing an inflammatory exudate [13,14].

A large number of risk factors for seroma formation that have been looked into include age, type of surgery, tumour size, number of positive lymph nodes, and patient’s BMI. Unfortunately, results of these studies are inconsistent, and in any case, the majority of these risk factors are unmodifiable. The challenge is to find a means to reduce the rate of seroma without significantly increasing operative time, blood loss, or other morbidity.

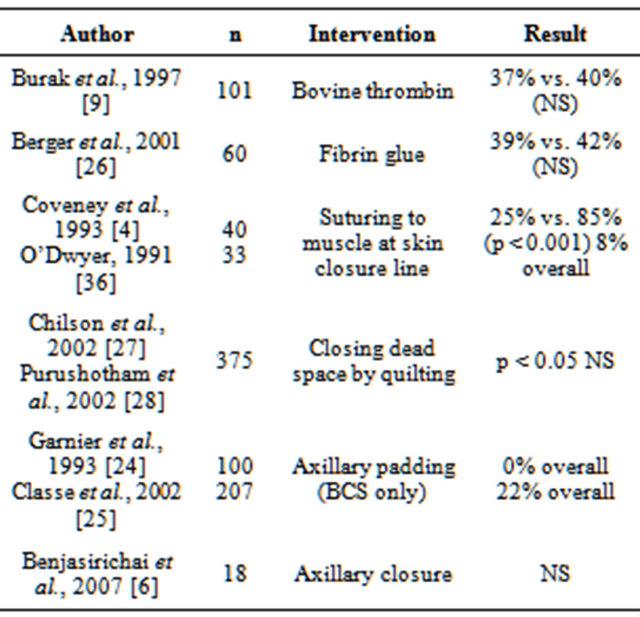

Only the age of the patient [15] and type of surgery performed [5,16] have been consistently shown to affect the rate of formation of seroma (Table 2).

Various studies have attempted to reduce seroma formation in order to improve outcome and reduce morbidity. Techniques that have been advocated over the years include shoulder immobilization [19,20], prolonged suction drainage [21] perioperative tranexamic acid [22], choice of surgical instrument [18,23], and obliteration of dead space [4,6,9,24-28].

Electrocautery has been described as possibly increasing the frequency of seroma. Contrary to popular belief, a study has shown that the length of time drains are left in place does not affect seroma rate. Few results have shown consistent benefit (Table 3).

Table 2. Studies of predictive factors of seroma formation following breast surgery.

Table 3. Studies examining interventions to reduce postoperative drainage following breast surgery (NS = nonsignificant result).

Time of initiation of arm movement has also been studied on the basis that chest wall motion and shoulder use create shearing forces that delay flap adherence, and that postoperative arm use acts as a pump forcing lymph into the empty axillary fossa. However, studies have shown no significant difference when delaying rehabilitation [29], and in fact the consequences of shoulder stiffness can be far greater than that of simple seroma.

Several studies have looked into tacking skin flaps to underlying muscle in an attempt to minimise dead space (Table 4). Halsted first described flap fixation in 1913 [3] and since, others have described individual methods to secure flaps and thereby close dead space. Some authors have used external sutures passing through the flap from the underlying muscle, but of course these may predispose to wound infection or local skin necrosis. Coveney et al. [4] as well as O’Dwyer [36] demonstrated that drainage volumes and seroma formation were significantly reduced when dead space was obliterated by suturing flaps to muscle down the skin closure suture line. Chilson et al. [37] advocated a similar tacking procedure, but tacked down the entire flap area using interrupted sutures.

In a similar vein, various authors including Lindsey et al. [38] have used topical fibrin glue in the operative site. Moore et al. [39] found good results using virally inactivated fibrin sealant, quoting a 30% reduction in median time to drain removal, and 23% reduction in cumulative drainage over 4 days, however, seroma formation was not examined as an outcome.

If it is believed that the largest potential dead space is the empty axillary apex after axillary dissection or indeed that seroma formation is contributed significantly to by disruption of axillary lymphatics, it follows that closure

Table 4. Studies examining techniques to obliterate dead space to reduce post-operative drainage following breast surgery.

of this space may prove useful. A few studies introduced the concept of axillary padding to reduce drainage volumes after axillary surgery. The axillae were padded with nearby tissue, and outcomes in terms of seroma formation were excellent. However, both main studies [24,25] carried out a limited axillary dissection, and were carried out on patients undergoing breast conservation.

We found only one other study looking at closing off the axillary space in patients undergoing mastectomy to reduce postoperative seroma. This was carried out in Thailand [6] involving 18 patients. The technique involved suturing the skin flap to underlying muscle at 3 points in the mid-axillary line, and found no significant difference of seroma thickness at the axilla measured ultrasonographically at two weeks.

We believe that post-operative fluid collections following mastectomy and axillary clearance arise from disrupted axillary lymphatics to a greater extent than serous fluid formation from mastectomy flaps. We have shown that reliably excluding the axillary fossa from the remainder of the mastectomy wound can considerably reduce post-operative drainage volume in this small group of patients. More importantly, this technique significantly reduces clinically apparent seromas after drain removal, thereby reducing the consequences of patient anxiety, discomfort and added morbidity.

5. Conclusion

Seromas are a common complication following mastectomy and axillary dissection. Many means of reduceing postoperative drainage volume and seroma rate have been studied, however results are inconsistent. Our technique of axillary exclusion has resulted in significantly reduced drainage volumes and fewer seromas.

REFERENCES

- D. R. Aitken and J. P. Minton, “Complications Associated with Mastectomy,” Surgical Clinics of North America, Vol. 63, No. 6, 1983, pp. 1331-1352.

- K. Tadych and W. L. Donegan, “Postmastectomy Seromas and Wound Drainage,” The Journal of Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 165, No. 6, 1987, pp. 483- 487.

- W. S. Halsted, “Developments in the Skin Grafting Operations for Cancer of the Breast,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 60, No. 6, 1913, pp. 416- 451. doi:10.1001/jama.1913.04340060008004

- E. C. Coveney, P. J. O’Dwyer, J. G. Geraghty and N. J. O’Higgins, “Effect of Closing Dead Space on Seroma Formation after Mastectomy—A Prospective Randomised Clinical Trial,” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1993, pp. 143-146.

- E. A. Gonzales, E. C. Saltzstein, C. S. Riedner and B. K. Nelson, “Seroma Formation Following Breast Cancer Surgery,” Breast Journal, Vol. 9, No. 5, 2003, pp. 385- 388. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09504.x

- V. Benjasirichai, A. Piyapant, C. Pokawattana and J. Dowreang, “Reducing Postoperative Seroma by Closing of Axillary Space,” Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, Vol. 90, No. 11, 2007, pp. 2321-2325.

- K. Kuroi, K. Shimozuma, T. Taguchi, H. Imai, H. Yamashiro, S. Ohsumi and S. Saito, “Pathophysiology of Seroma in Breast Cancer,” Breast Cancer, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2005, pp. 288-293. doi:10.2325/jbcs.12.288

- C. J. Pogson, A. Adwani and S. R. Ebbs, “Seroma Following Breast Cancer Surgery,” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 29, No. 9, 2003, pp. 711-717. doi:10.1016/S0748-7983(03)00096-9

- W. E. Burak, P. S. Goodman, D. C. Young and W. B. Farrar, “Seroma Formation Following Axillary Dissection for Breast Cancer: Risk Factors and Lack Of Influence of Bovine Thrombin,” Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 64, No. 1, 1997, pp. 27-31. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199701)64:1<27::AID-JSO6>3.0.CO;2-R

- A. Agrawal, A. A. Ayantunde and K. L. Cheung, “Concepts of Seroma Formation and Prevention in Breast Cancer Surgery,” ANZ Journal of Surgery, Vol. 76, No. 12, 2006, pp. 1088-1095. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03949.x

- K. Kuroi, K. Shimozuma, T. Taguchi, H. Imai, H. Yamashiro, S. Ohsumi and S. Saito, “Effect of Mechanical Closure of Dead Space on Seroma Formation after Breast Surgery,” Breast Cancer, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2006, pp. 260- 265. doi:10.2325/jbcs.13.260

- J. Bonnema, D. A. Ligtenstein, T. Wiggers and A. N. van Geel, “The Composition of Serous Fluid after Axillary Dissection,” European Journal of Surgery, Vol. 165, No. 1, 1999, pp. 9-13. doi:10.1080/110241599750007441

- J. A. McCaul, A. Aslaam, R. J. Spooner, I. Louden, T. Cavanagh and A. D. Purushotham, “Aetiology of Seroma Formation in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Breast Cancer,” Breast, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000, pp. 144-148. doi:10.1054/brst.1999.0126

- K. Jain, R. Sowdi, A. D. Anderson and J. MacFie, “Randomized Clinical Trial Investigating the Use of Drains and Fibrin Sealant Following Surgery for Breast Cancer,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 91, No. 1, 2004, pp. 54- 60. doi:10.1002/bjs.4435

- W. T. Y. Loo and L. W. C. Chow, “Factors Predicting Seroma Formation after Mastectomy for Chinese Breast Cancer Patients,” Indian Journal of Cancer, Vol. 44. No. 3, 2007, pp. 99-103. doi:10.4103/0019-509X.38940

- E. Hashemi, A. Kaviana, M. Najafi, M. Ebrahimi, H. Hooshmand and A. Montazeri, “Seroma Formation after Surgery for Breast Cancer,” World Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 2, 2004, p. 44. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-2-44

- H. R. Unalp and M. A. Onal, “Analysis of Risk Factors Affecting the Development of Seromas Following Breast Cancer Surgeries: Seromas Following Breast Cancer Surgeries,” The Breast Journal, Vol. 13, No. 6, 2007, pp. 588-592. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00509.x

- F. Lumachi, A. A. Brandes, P. Burelli, S. M. M. Basso, M. Lacobone and M. Ermani, “Seroma Prevention Following Axillary Dissection in Patients with Breast Cancer by Using Ultrasound Scissors: A Prospective Clinical Study,” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 30, No. 5, 2004, pp. 526-530. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2004.03.003

- C. D. Knight Jr., F. D. Griffen and C. D. Knight Sr., “Prevention of Seromas in Mastectomy Wounds. The Effect of Shoulder Immobilization,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 130, No. 1, 1995, pp. 99-101. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430010101021

- W. E. Stebhens, “Postmastectomy Serous Drainage and Seroma: Probably Pathogenesis and Prevention,” ANZ Journal of Surgery, Vol. 73, No. 11, 2003, pp. 877-880. doi:10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02832.x

- N. C. Estes and J. L. Glover, “Use of Vacutainer Suction as a Convenient Method of Resolving Postmastectomy Seromas,” Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics, Vol. 155, No. 4, 1982, pp. 561-562.

- D. Oertli, U. Laffer, F. Haberthuer, U. Kreuter and F. Harder, “Perioperative and Postoperative Tranexamic Acid Reduces the Local Wound Complication Rate after Surgery for Breast Cancer,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 81, No. 6, 1994, pp. 856-859. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800810621

- K. A. Porter, S. O’Connor, E. Rimm and M. Lopez, “Electrocautery as a Factor in Seroma Formation Following Mastectomy,” American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 176, No. 1, 1998, pp. 8-11. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00093-2

- J. M. Garnier, A. Hamy, J. M. Classe, O. Laborde, P. Sagot, P. Lopes, G. Boog, J. C. Drianno and Y. Guillard, “A New Approach to the Axilla: Functional Axillary Lymphadenectomy and Padding,” Journal of Gynaecology, Obstetrics and Reproductive Biology, Vol. 22, No. 3, 1993, pp. 237-242.

- J. M. Classe, P. F. Dupre, T. François, S. Robard, J. L. Theard and F. Dravet, “Axillary Padding as an Alternative to Closed Suction Drain for Ambulatory Axillary Lymphadenectomy: A Prospective Cohort of 207 Patients with Early Breast Cancer,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 137, No. 2, 2002, pp. 169-172. doi:10.1001/archsurg.137.2.169

- A. Berger, C. Tempfer, B. Hartmann, P. Kornprat, A. Rossmann, G. Neuwirth, A Tulusan and E. Kubista, “Sealing of Postoperative Axillary Leakage after Axillary Lymphadenectomy Using a Fibrin Glue Coated Collagen Patch: A Prospective Randomised Study,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, Vol. 67, No. 1, 2001, pp. 9-14. doi:10.1023/A:1010671209279

- T. R. Chilson, F. D. Chan, R. R. Lonser, T. M. Wu and D. R. Aitken, “Seroma Prevention after Modified Radical Mastectomy,” American Surgeon, Vol. 58, No. 12, 1992, pp. 750-754.

- A. D. Purushotham, E. McLatchie, D. Young, W. D. George, S. Stallard, J. Doughty, D. C. Brown, C. Farish, A. Walker, K. Millar and G. Murray, “Randomized Clinical Trial of No Wound Drains and Early Discharge in the Treatment of Women with Breast Cancer,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 89, No. 3, 2002, pp. 286-292. doi:10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.02031.x

- D. J. Browse, D. Goble and P. A. Jones. “Axillary Node Clearance: Who Wants to Immobilize the Shoulder?” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 22, No. 6, 1996, pp. 569-570. doi:10.1016/S0748-7983(96)92164-2

- C. Y. Chen, A. L. Hoe and C. Y. Wong, “The Effect of a Pressure Garment on Post-Surgical Drainage and Seroma Formation in Breast Cancer Patients,” Singapore Medical Journal, Vol. 39, No. 9, 1998, pp. 412-415.

- J. Zavotsky, R. C. Jones, M. B. Brennan and A. E. Giuliano, “Evaluation of Axillary Lymphadenectomy without Axillary Drainage for Patients Undergoing Breast-Conserving Therapy,” Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1998, pp. 227-231. doi:10.1007/BF02303777

- D. C. Rice, S. M. Morris, M. G. Sarr, M. B. Farnell, J. A. van Heerden, C. S. Grant, C, M. Rowland, D. M. Ilstrup and J. H. Donohue, “Intraoperative Topical Tetracycline Sclerotherapy Following Mastectomy: A Prospective, Randomized Trial,” Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 73, No. 4, 2000, pp. 224-227. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(200004)73:4<224::AID-JSO7>3.0.CO;2-0

- R. Gupta, K. Pate, S. Varshney, J. Goddard and G. T. Royle, “A Comparison of 5-Day and 8-Day Drainage Following Mastectomy and Axillary Clearance,” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2001, pp. 26-30. doi:10.1053/ejso.2000.1054

- J. Barwell, L. Campbell, R. M. Watkins and C. Teasdale, “How Long Should Suction Drains Stay in after Breast Surgery with Axillary Dissection?” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Vol. 79, No. 6, 1997, pp. 435-437.

- R. Anand, R. Skinner, G. Dennison and J. A. Pain, “A Prospective Randomised Trial of Two Treatments for Wound Seroma after Breast Surgery,” European Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 28, No. 6, 2002, pp. 620-622. doi:10.1053/ejso.2002.1298

- P. J. O’Dwyer, “Axillary Dissection in Primary Breast Cancer,” British Medical Journal, Vol. 302, No. 6773, 1991, pp. 360-361. doi:10.1136/bmj.302.6773.360

- T. R. Chilson, F. D. Chan, R. R. Lonser, T. M. Wu and D. R. Aitken, “Seroma Prevention after Modified Radical Mastectomy,” American Surgeon, Vol. 58, No. 12, 1992, pp. 750-754.

- W. H. Lindsey, T. M. Masterson, W. D. Spotnitz, M. C. Wilhelm and R. F. Morgan, “Seroma Prevention Using Fibrin Glue in a Rat Mastectomy Model,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 125, No. 3, 1990, pp. 305-307. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410150027005

- M. Moore, W. E. Burak Jr., E. Nelson, T. Kearney, R. Simmons, L. Mayers and W. D. Spotnitz, “Fibrin Sealant Reduces the Duration and Amount of Fluid Drainage after Axillary Dissection: A Randomized Prospective Clinical Trial,” Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Vol. 192, No. 5, 2001, pp. 591-599. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(01)00827-4

NOTES

*Current affiliation: Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth, United Kingdom.