World Journal of Cardiovascular Diseases

Vol.08 No.07(2018), Article ID:85970,9 pages

10.4236/wjcd.2018.87031

Prevalence, Pattern and Evolution of Rheumatic Heart Disease: About 120 Cases at Mother-Children University Hospital Luxembourg (MC UHL), Bamako (Mali)

Bâ Hamidou Oumar1*, Maiga Asmaou Kéita2, Doumbia Coumba Thiam3, Maiga Salma Souleimane2, Sidibé Noumou1, Sangaré Ibrahima1, Camara Youssouf3, Sidibé Salimata1, Diallo Souleymane2, Menta Ichaka1, Diarra Mamadou Bocary2

1CHU Gabriel Touré, Bamako, Mali

2CHU Mère Enfant le Luxembourg, Bamako, Mali

3CHU Sidy Bocar Sall, Kati, Mali

Copyright © 2018 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: June 2, 2018; Accepted: July 10, 2018; Published: July 13, 2018

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and its complications including rheumatic heart disease (RHD) remain one of the leading causes of cardiovascular disease worldwide. In our setting with no cardiac surgery, data on RHD are therefore important to point out the need for such structure. In this study, we therefore describe rheumatic disease in terms of prevalence, patients’ characteristics and management of patients. Methods: We performed a retrospective study from May to September 2012, involving children aged 3 to 15 years old and seen at the Mother and Child University Hospital Luxembourg (MC UHL). Included were all children diagnosed with RHD. The diagnosis of rheumatic fever (RF) was defined using the revised Jones criteria from 1992 and RHD defined according to the WHO/NIH joint criteria. Data of interview, clinical examination, complementary and those on evolution were recorded. Results: We found an hospital prevalence of 6.2%. Mean age was 15.33 years ± 6.005 (3 to 36), females representing 54.2% and students 70%. Mitral regurgitation (MR), Mitral Stenosis (MS) and concomitant MR + MS were most found RHD with resp. 43.3%, 15% and 13.3%. Complications occurred in 74.1% before surgery. An operative indication was set in 90% of all cases whereas only 36% underwent surgery. After surgery immediate complications were dominated by anemia (11.6%) and late ones by heart failure in 18.5% of cases. Conclusion: Despite advances in medical diagnostic approach and therapeutical progress which partly explained the relatively high prevalence, the evolution of rheumatic heart disease in our context is unfavorable due to the lack of a surgical management structure. While waiting for a cardiology institute, the focus should be on information and awareness in primary prevention.

Keywords:

Retrospective, Acute Rheumatic Fever, Rheumatic Heart Disease, Bamako

1. Introduction

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is a postinfectious, nonsuppurative sequela of pharyngeal infection with Streptococcus pyogenes, or Group A β hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS). Of the associated symptoms, only damage to the valve tissue within the heart, or rheumatic heart disease (RHD), can become a chronic condition leading to congestive heart failure, strokes, endocarditis, and death [1] .

ARF and its complications RHD remain one of the leading causes of cardiovascular disease worldwide [2] and constitute a heavy burden for developing countries with differences between countries, incidence and prevalence varying considerably [3] [4] [5] . ARF and its sequel RHD continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality in developing countries and have been under-recognized as a global health problem for decades [6] .

Many studies have been devoted to this condition first on clinical criteria [7] [8] [9] and then more and more echocardiographic [10] [11] [12] [13] . The issues of its management in our context have already been underlined in other works [14] with notably the absence of local cardio-surgical possibilities.

Strategies [2] [15] for fighting against ARF and its consequences include the establishment of prevalence registers, which are rare. To our knowledge, only the REMEDY (prospective) and the VALVAFRIC (retrospective) [16] registers answer this question.

The comparison of the data encounters difficulties arising from the various collection methods for data. RF is a disease of poverty [17] , the situation in most developing countries like ours. Besides diagnostic issues are common due to the unavailability/oldness of echocardiography machines and rarity of pediatric cardiologists. At the study time our institution reached 5 years patients’ management in collaboration with foreign non governmental organizations. All these facts constitute up to day challenges in diagnostic and management. We then aim to describe rheumatic disease in terms of prevalence, patients characteristics and management of patients, in a study conducted by pediatric cardiologists and using last generation echocardiography machine.

2. Methodology

Our study was retrospective from May to September 2012. It involved data from children aged 3 to 15 years old and seen in the MC UHL during the study period. All children with a transthoracic echocardiographic (TTE) diagnosis of RHD were selected.

MC UHL, the study site had at the study period an echocardiographic machine from type Vivid 7 Pro from General Electric, which serves for all echocardiography requests. This machine had 3 probes from 3, 5 and 10 MHz fulfilling the requirements for children and adolescents.

The diagnosis of RF was defined using the revised Jones criteria from 1992 [18] .

RHD was defined as patient:

1) with history of RF ( more than 3 months) or not

2) with recent ( less than 3 months ) or past episode of RF

3) clinical or echocardiographic finding of

- valvular heart disease ( mitral regurgitation, mitral stenosis, aortic insufficiency/stenosis) compatible with rheumatic heart disease.

- myocardial involvement.

- pericardial involvement.

The data of interview, clinical examination, labor assessments (frontal chest X-ray, ECG, echocardiography, biology including NFS, VS, ASLO, CRP, fibrinemia) and those on evolution were recorded.

The data were collected on survey forms and analyzed with SPSS version 18 software.

3. Results

We recorded 120 cases of rheumatic heart disease out of 1949 consultations, giving an hospital prevalence of 6.2%. The average age was 15.33 years ± 6.005 from 3 to 36 years. Females with 54.2% and students with 70% predominated (Table 1).

A history of polyarthralgia and recurrent throat pain was found at equal frequency in 79 patients (65.8%).

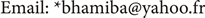

Among the revised Jones criteria (1992), carditis, fever, and ASO/CRP elevation were highest in 05.08%, 36.7% and 17.5% of patients respectively (Diagram 1).

The clinical signs were dominated by dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, fever and cough in 51.7%, 40%, 37.5%, 36% and 35.8%, respectively. Cardiomegaly was present in 86.3% of the chest x-rays. The association left atrial hypertrophy (LAH) and left ventricular hyperthophy (LVH) and isolated LVH were the most represented electrical signs (Table 2).

The selected diagnoses were dominated by stable chronic rheumatic heart disease with 72.5% followed by progressive RHD with 26.7%. Only one case of acute RHD was found.

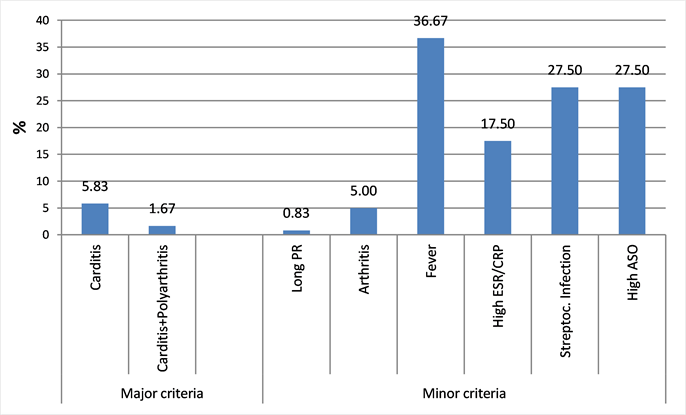

RHD were dominated by Mitral regurgitation (MR) with 43.3% of all cases followed by Mitral Stenosis (MS) with 15% (Diagram 2).

Complications noted in 81 patients preoperatively were dominated by heart failure (74.1%). Five patients died before they get chance to be operated (Table 3).

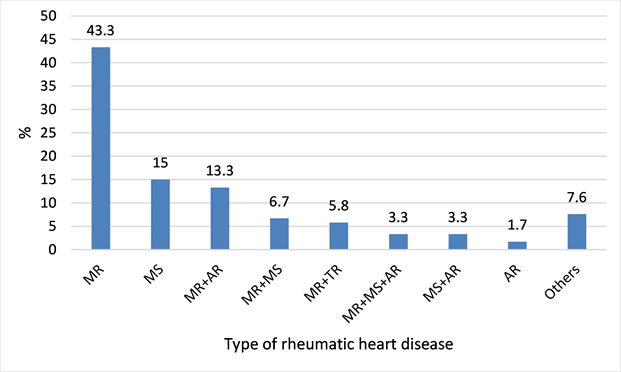

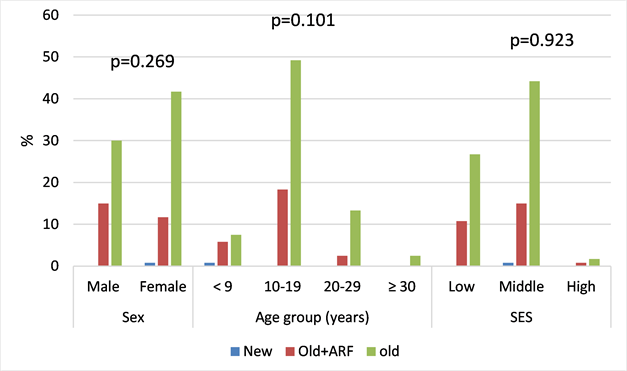

From a total of 108 patients (90% of the sample) had an operative indication and among them 43 patients or 36% underwent surgery (Diagram 3). Chronic rheumatic heart disease was more represented with p being not statistically significantly (Diagram 4).

Among the operated patients, the immediate postoperative complications were dominated by anemia (11.6%) and late ones by heart failure in 18.5% of cases (Table 4).

Table 1. Socio-demographics of the sample of 120 patients in the MC UHL.

Table 2. Signs (functional and labor assessment) distribution in the sample of 120 patients.

*LAH: left atrial hypertrophy **LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy ***RVH: right ventricular hypertrophy.

Table 3. Distribution of complications before cardiac surgery and evolution.

Table 4. Distribution of post surgery complications for 43 patients.

Diagram 1. Distribution of revised 1992 Jones criteria in the sample of 120 cases in the MC UHL.

Diagram 2. Distribution of rheumatic heart diseases in the sample of 120 cases in the MC UHL.

Diagram 3. distribution of patients related to the need and performing of surgery in the sample of 120 cases in the MC UHL.

Diagram 4. sociodemographics related to type of rheumatic heart diseases for 120 cases seen in the MC UHL.

4. Discussion

Our study is one of the first to use clinical and systematically echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis of RHD.

Using of clinical examination was found to underestimate the prevalence. Using the WHO/NIH joint criteria [19] pointed out this fact.

The prevalence of 6.2% found in our study is higher than that found in a 1994 study by Diallo [20] in Mali and Diao et al. in Senegal [21] , probably because of advances in cardiac imaging. At the time of the study the MC UHL had a device of last generation. This prevalence is still high despite the progress made in terms of geographical health coverage and affordability of health services. But as other authors have pointed out, the increase in prevalence may also be due to improved care [1] , leading to a higher detection rate.

Our mean age is that of occurrence of rheumatic heart disease.

Sex prevalence varies from study to study. In ours female sex predominated as found by Diao [21] , Moyen [9] and Sliwa [22] .

Full cases with major Jones criteria (Diagram 1) were rarely found, this may be due to previous treatments often self-medication or prescribed by practitioners, because the hospital is rarely the first point of care. Similarly, the radiological and electrical paraclinical signs show less advanced disease stages with less repercussion at baseline (Table 2).

MR and MS are the most common post-rheumatic valve involvement as found by several authors [1] [9] [11] and also in our previous studies.

We didn’t find any difference of rheumatic heart disease types based on socio-economic status.

In our sample there was a surgical indication in 90% of all cases, but only 36% of the sample was operated outside Mali thanks to the support of Non Governmental Organizations which unfortunately can not cover the need in surgery for all these patients. The consequence is a progression towards complications with cardiac decompensation episodes at the top (Table 3). The majority of African countries at the time of the survey did not have a surgical management structure. Sani et al. [23] reported a proportion of 31.8% complications at the time of diagnosis.

Although immediate postoperative complications are relatively easy to manage, such as anemia, late complications such as prosthetic dysfunction or disinsertion of the prosthesis (Table 4) are difficult to manage without the possibility of surgery.

5. Conclusion

Despite advances in medical diagnostic approach and progress in management which partly explain the relatively high prevalence, the evolution of rheumatic heart disease in our context is unfavorable due to the lack of a surgical management structure. While waiting for the crowning of efforts for a cardiology institute, the focus should be on information and awareness in primary prevention.

Limits

Our study was retrospective with issues due to the completeness of the data, which did not allow us for example to determine the techniques used for the surgery and thus likely to explain the postoperative complications.

Cite this paper

Oumar, B.H., Kéita, M.A., Thiam, D.C., Souleimane, M.S., Noumou, S., Ibrahima, S., Youssouf, C., Salimata, S., Souleymane, D., Ichaka, M. and Bocary, D.M. (2018) Prevalence, Pattern and Evolution of Rheumatic Heart Disease: About 120 Cases at Mother-Children University Hospital Luxembourg (MC UHL), Bamako (Mali). World Journal of Cardiovascular Diseases, 8, 319-327. https://doi.org/10.4236/wjcd.2018.87031

References

- 1. Seckeler, M.D. and Hoke, T.R. (2011) The Worldwide Epidemiology of Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. Clinical Epidemiology, 3, 67-84. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S12977

- 2. World Health Organization (2001) Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organization, Geneva, Technical Report Series No. 923.

- 3. Watkins, D.A., Johnson, C.O., Colquhoun, S.M., et al. (2017) Global, Regional and National Burden of Rheumatic Heart Disease, 1990-2015. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 713-722. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

- 4. Sliwa, K., Carrington, M., Mayosi, B.M., et al. (2010) Incidence and Characteristics of Newly Diagnosed Rheumatic Heart Disease in Urban African Adults: Insights from the Heart of Soweto Study. European Heart Journal, 31, 719-727. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp530

- 5. Engel, M.E., Haileamlak, A., Zühlke, L., et al. (2015) Prevalence of Rheumatic Heart Disease in 4720 Asymptomatic Scholars from South Africa and Ethiopia. Heart, 101, 1389-1394. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307444

- 6. Zühlke, L.J. and Steer, A.C. (2013) Estimates of the Global Burden of Rheumatic Heart Disease. Global Heart, 8, 189-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2013.08.008

- 7. Bertrand, E., Coly, M., Chauvet, J., et al. (1979) Etude de la prévalence des cardiopathies, notamment rhumatismales, en milieu scolaire en Cote d’Ivoire. Bulletin de l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé, 57, 471-474.

- 8. Ibrahim-Khalil, S., Elhag, M., Ali, E., et al. (1992) An Epidemiological Survey of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease in Sahafa Town, Sudan. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 46, 477-479. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.46.5.477

- 9. Moyen, G., Okoko, A., Cardorelle, A.M., et al. (1996) Rhumatisme articulaire aigu et cardiopathies rhumatismales de l’enfant à Brazzaville. Médecine d’Afrique Noire, 46, 258-263.

- 10. Reményi, B., Wilson, N., Steer, A., et al. (2012) World Heart Federation Criteria for Echocardiographic Diagnosis of Rheumatic Heart Disease—An Evidence Based Guideline. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 9, 297-309. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

- 11. Marijon, E., Ou, P., Celermajer, D.S., et al. (2007) Prevalence of Rheumatic Heart Disease Detected by Echocardiographic Screening. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 470-476. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa065085

- 12. Nkoke, C., et al. (2016) Echocardiographic Pattern of Rheumatic Valvular Disease in a Contemporary Sub-Saharan African Pediatric Population: An Audit of a Major Cardiac Ultrasound Unit in Yaounde, Cameroon. BMC Pediatrics, 16, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0584-z

- 13. Diallo, M., Tapia, M.D., Scheel, J.N., Sanogo, K.M., Ouane, O., Sow, S.O., Dale, J. and Kotloff, K.L. (2012) Community-Based Screening with Echocardiography for Rheumatic Heart Disease among School-aged Children and Adults in Bamako, Mali (Abstract). Bethesda, Maryland.

- 14. Diarra, M.B., BA, H.O., Sanogo, K.M., Diarra, A. and Touré, M.K. (2006) Le cout des évacuations cardiovasculaires et les besoins en traitement chirurgical et interventionnel au Mali. Cardiologie Tropicale, 32, 66-68.

- 15. Wyber, R. (2013) A Conceptual Framework for Comprehensive Rheumatic Heart Disease Control Programs. Global Heart, 8, No. 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2013.07.003

- 16. Kingué, S., Ba, S.A., Balde, D., Diarra, M.B., et al. (2016) The VALVAFRIC Study: A Registry of Rheumatic Heart Disease in Western and Central Africa. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases, 109, 321-329.

- 17. Carapetis, J.R. (2007) Rheumatic Heart Disease in Developing Countries. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 439-441. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp078039

- 18. Dajani, A.S., Ayoub, E., Bierman, F.Z., et al. (1992) Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever: Jones Criteria, 1992 Update. JAMA, 268, 2069-2073. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.268.15.2069

- 19. Beaton, A., et al. (2012) Echocardiography Screening for Rheumatic Heart Disease in Ugandan Schoolchildren. Circulation, 125, 3127-3132. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092312

- 20. Diallo, B.A. and Touré, M.K. (1994) Etude épidémiologique, clinique et évolutive de 96 cas de valvulopathies rhumatismales. Cardiologie Tropicale, 20, 121-124.

- 21. Diao, M., Kane, Ad., Doumbia, A.S., Leye, M.M.C.B.O., Mbaye, A., Kane, A., Diop, I.B., Sarr, M., Ba, S.A. and Diouf, S.M. (2005) Cardiopathies Rhumatismales Evolutives: A propos de 17 cas colligés au CHU de Dakar. Med Trop, 65, 339-342.

- 22. Sliwa, K., Carrington, M., Mayosi, B.M., Zigiriadis, E., Mvungi, R. and Stewart, S. (2010) Incidence and Characteristics of Newly Diagnosed Rheumatic Heart Disease in Urban African Adults: Insights from the Heart of Soweto Study. European Heart Journal, 31, 719-727. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp530

- 23. Sani, M., Karaye, K. and Borodo, M.M. (2007) Prevalence and Pattern of Rheumatic Heart Disease in the Nigerian Savannah: An Echocardiographic Study. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 18, 295-299.