Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.4(2013), Article ID:35244,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.34046

Assessment of quality of postnatal care services offered to mothers in Dedza district, Malawi

![]()

1Dedza District Hospital, Dedza, Malawi

2Research Directorate, Kamuzu College of Nursing, University of Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi

3Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Kamuzu College of Nursing, University of Malawi, Blantyre, Malawi

4Department of Maternal and Child Health, Kamuzu College of Nursing, University of Malawi, Blantyre, Malawi

5Dean of Faculty, Kamuzu College of Nursing, University of Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi

Email: *aomaluwa@kcn.unima.mw

Copyright © 2013 Lydia Kanise Chimtembo et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 27 March 2013; revised 27 April 2013; accepted 15 May 2013

Keywords: Quality Postnatal Care; Reproductive Health Standards; Postnatal Care Structure; Process and Outcome; Maternal and Neonatal Health; Postnatal Care Standards

ABSTRACT

This study was conducted to assess quality of postnatal care that midwives provide to women seeking postnatal services in health facilities in Dedza district, the central region of Malawi. The study design was descriptive cross sectional and utilized quantitative data collection and analysis method to determine structural, process and outcome components of postnatal care in two facilities that offer emergency obstetric and neonatal care and five that offer basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care. All 60 midwives who were providing postnatal care during the time of study in the district were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. In addition, the midwives actual practice was observed and compared to a standard checklist on postnatal care practice which was developed by the Malawi Ministry of Health. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0. Results show that structure for providing postnatal counseling services was inappropriate and inadequate. Furthermore, the contents of postnatal services were below reproductive health standards because the clients were neither monitored nor examined physically on discharge. On average, all the seven facilities scored 48% on postnatal services rendered which is far below the recommended 80% according to the Reproductive Health Standards. There is a need to provide basic infrastructure in all the basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care facilities. In addition, refresher training courses for midwives in maternal and neonatal health with emphasis on postnatal care are recommended. There is also a need to restructure the maternal and neonatal health departments in the facilities so that the postnatal care units become standalone priority sites to improve the quality of the postnatal care services rendered.

1. INTRODUCTION

Postnatal period is a six-week interval between birth of a new born and the return of the reproductive organs to their normal non pregnant state [1]. Postnatal period is a vulnerable time because most maternal and new born deaths occur during this period [2]. Globally, over 500,000 women die of child birth every year with over 90% of the deaths occurring in the developing countries [3]. Annual maternal mortality rates in the developed countries such as the United Kingdom and United States of America are estimated at 8 and 16 per 100,000 live births respectively [4]. In some African countries such as South Africa, maternal mortality rate is estimated at 237 per 100,000 live births, while in the Sub Sahara African countries the rates are over 400 per 100,000 live births [4]. In Malawi, the maternal mortality is estimated at 675 per 100,000 live births [5].

Postnatal care (PNC) is the most neglected area in the health care delivery system despite being very important time for the provision of interventions that are vital to the health of both the mother and the new born [6]. Consequently, serious complications which account for two thirds of all maternal and neonatal deaths occur during the postnatal period [6]. In Malawi, 60% of the maternal deaths occur during the postpartum period, of which 70% occur during the first week and 30% within 2 weeks afer delivery [7]. To reduce these deaths, the Government of Malawi formulated a Roadmap for the Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal mortality. The roadmap recommends that all women who deliver in a health facility should receive a postnatal health checkup within the first 24 hours after delivery. In addition, all women who deliver outside a health facility should be referred to a health facility for postnatal check up within 12 hours of delivery [8]. The Malawi Ministry of Health reported that 97% of all facilities in the country provided postnatal care services but 93% of the maternal deaths occurred in the facilities with 69% of them occurring after the women had already delivered. Traditionally, the strategies to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality have focused on pregnancy and delivery periods with minimal attention given to postnatal period. Consequently postpartum sepsis and hemorrhage account for 18 and 34% respectively of all maternal deaths in Malawi [9]. The contributing factors to deaths in the postpartum period for the hospital deliveries suggest that there may be substandard care being offered to women during the management of postpartum complications [10].

Dedza is one of the districts in Malawi with high maternal mortality rates. According to the unpublished Maternal and Neonatal Report for the district in 2009, there were 13 maternal deaths with 11 of them occurring during the postnatal period. The district had also 266 women that developed child birth complications with 42 of them developing postpartum hemorrhage, 66 with sepsis and 158 pregnancy induced hypertension. In addition, 138 neonates had sepsis and 58 had asphyxia. The district records these statistics despite the fact that it has two Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (EmONC) and 7 Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (BEmONC) facilities. In addition, the EmONC and BEmONC facilities are staffed with midwives that are trained to offer essential postpartum care and are also equipped with extra human and material resources to provide quality care services to clients. Despite the availability of extra resources and trained midwives, rate of complications and deaths in the postpartum period in the district is high even among women that are delivering in the health facilities. This study therefore, aimed at assessing the quality of care that is offered to postpartum women at the EmONC and BEmONC facilities in the district. Specifically the study assessed the three elements of Donabedian quality of care [11], which are structure, process and outcome.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Design

The study design was descriptive cross sectional and utilized quantitative data collection and analysis method to determine quality of postpartum care in sites that were designated as EmoNC and BEmoNC health facilities in Dedza district. The study was guided by Donabedian theoretical framework on quality of health care [11]. The structure component of the framework guided the examination of the setting in which PNC is provided. The process examined activities involved in PNC service provision and the outcome evaluated the setting and contents of PNC in line with the stipulated standards of care.

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted in Dedza District of the Central Region of Malawi. The district shares boundaries with four other districts and the Republic of Mozambique. The total population in the district is 671,137, with 154,362 being women of childbearing age. The expected number of deliveries per year is 33,000 [5]. The facilities that were targeted for this study were those that provide EmONC (Dedza district and Mua Mission Hospitals). In addition, all the seven health centers which provide BEmONC (Kasina, Mtendere, Bembeke, Golomoti, Kaphuka, Mtakataka and Lobi) were included in the study.

2.3. Sample Size

All the two EmONC and seven BEmONC facilities in the district were targeted. These facilities are manned by a total of 140 midwives. During the study 60 midwives (84% of the total number of midwives) were available on duty and they all consented and participated in the study.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study targeted all consenting midwives both Registered and Enrolled Midwives that were working in the postnatal care of the EmONC and BEmONC facilities in Dedza district. The study excluded facilities that were not designated as EmONC or BEmONC sites and midwives who were working in facilities that were not designated as EmONC and BEmONC. In addition midwives who were working in other sections of the facility other than postnatal wards, students and Caucasian midwives in Christian Healthcare Association of Malawi (CHAM) institutions that were working on special programs were excluded from the study.

2.5. Data Collection

Data was collected by the senior author, who is a Registered nurse-midwife. To prevent Hawthorne effect during data collection, observations on practice were initially done before the midwives were interviewed. Hawthorne effect refers to psychological response in which participants of research change their behavior because they know that they are being observed [13]. To prevent this effect, all the study sites were visited and the researcher worked with midwives for 3 days from morning to knock off time. The midwives were observed as they provided postnatal care to the clients. At each facility, observations on the quality of postnatal care were done every day and the service delivery practices were recorded to determine the outcomes of postpartum care.

A structured questionnaire that was formulated based WHO postnatal guidelines and Reproductive Health (RH) standards of care was administered to the clients to determine their knowledge of postnatal care which was compared to their actual practice. A checklist was used to collect data on the assessment of structure in terms of availability of human and material resources, infrastructure and midwives’ knowledge on postnatal health assessment, health education and counseling on postnatal care concepts. Regarding the process of care, a checklist was used to mark whether the midwives offered care in accordance with the procedures as recommended in the RH standard of care. The RH standards were checked against actual practice based on observations on midwives during the delivery of PNC services. The components of care observed included client monitoring, physical examination, client education and counseling. The outcome component was determined with the use of a20 criteria checklist derived from RH standards and WHO guidelines which was used to measure availability of basic infrastructure, materials and resources for providing postnatal care, and the education content that was provided to women during postpartum care and at discharge. A facility was supposed to score at least 80% on the standard of care to be considered as providing quality of RH care in which postnatal care is a component.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS software version 16.0. Descriptive statistics were computed for the structure and process variables and the results are presented as frequencies, means and percentages. Mean scores for the outcome components of quality of care were computed as percentages. The percentages were compared to the cut off point of at least 80% for a facility to be deemed to provide quality of care.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The study was approval by College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, which is the internal ethical review board for Kamuzu College of Nursing. The District Health Officer for Dedza approved the study to be conducted in the health facilities that are situated in the district. All participants gave an informed consent before interviews were conducted. All other ethical issues such as maintaining confidentiality and avoiding harm were strictly observed during the study.

2.8. Limitations of the Study

The study was conducted in one district hence the results may not be generalized to the whole country although the trend is similar in most health facilities of the country.

2.9. The Findings

2.9.1. Structure as Assessed by Availability of Human Resources and Physical Infrastructure

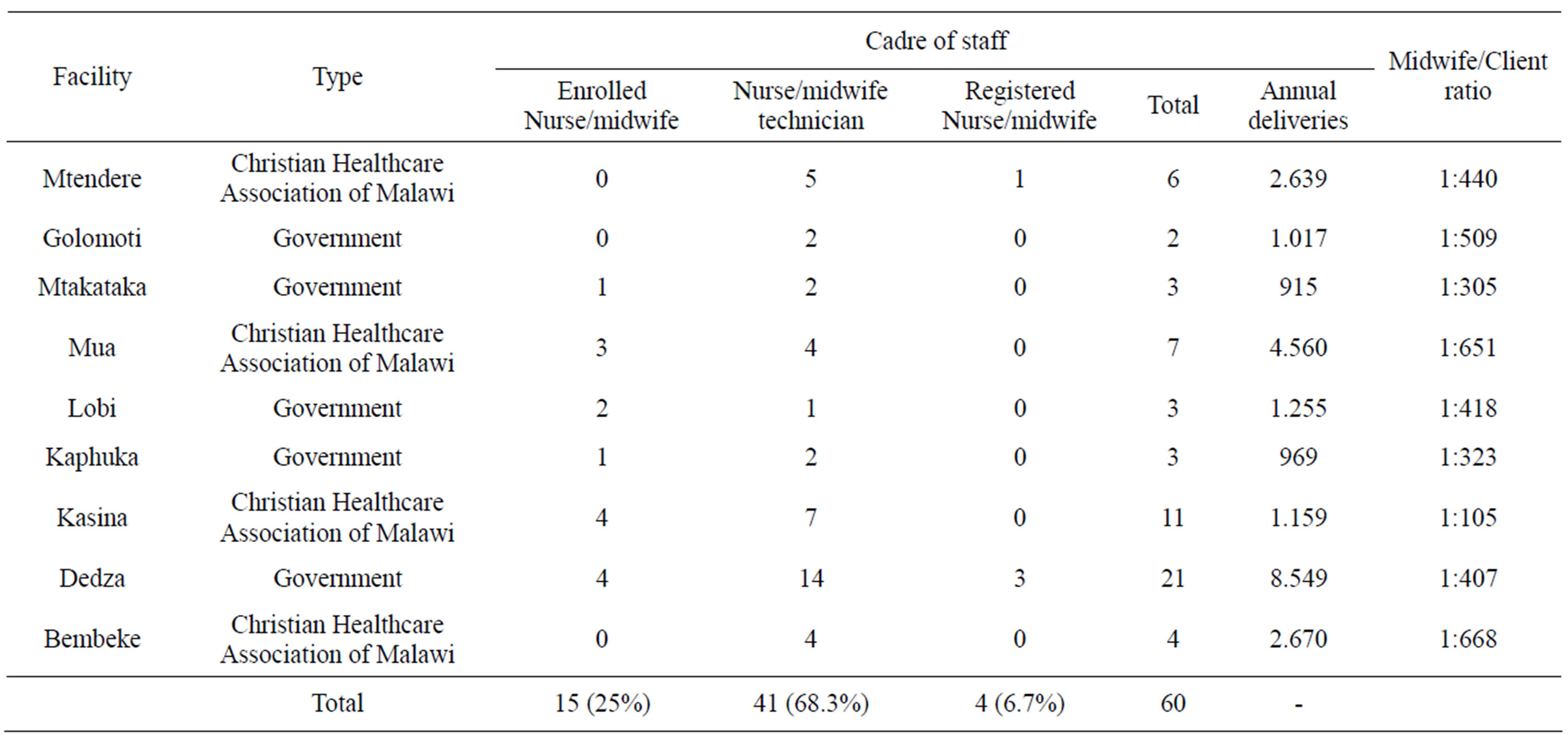

1) Human resources A total of 9 facilities were selected for the study out of which 4 belonged to CHAM while the other 5 belonged to the government and were administered through the Ministry of Health (Table 1).The cadre of staff, midwife-client ratio and the estimated number of deliveries per year is shown in Table 1.

Most of the midwives (68.3%) were nurse-midwife technicians and the registered nurse-midwives were few (6.7%). Only two facilities had registered midwives showing that most of the facilities lacked appropriate skill mix of professional and technician nurse midwives. The lowest midwife-client ratio (1:105) was recorded at Masina Health Center while the highest (1:668) was recorded at Bembeke health center. Both health centers were CHAM facilities. The participants’ years of experience ranged from 1 to 15 with a mean of 4 years. Majority of midwives (60%) acquired their midwifery qualification more than five years prior to the study whilst 32% qualified as practicing nurses three to four years prior to the study.At the health centers, the midwives were responsible for managing the whole maternity wing comprising the antenatal, labor and delivery and postnatal wards.

2) Physical Infrastructure The two EmONC facilities (Dedza district and Mua mission) hospitals had special examination rooms for postnatal care and all the BEmONC facilities (health centers) had improvised space within their labor wards for physical examination. When the impoverished rooms were engaged with other activities, the postnatal women were discharged without any examination.

3) Essential Equipment, Drugs and Guidelines All the facilities did not have postnatal care monitoring equipment like sphygmomanometer and thermometers in their maternity departments. In addition, guidelines and teaching aids for postnatal care were not available in all the facilities. However, all the facilities had essential drugs such as panado and iron tablets. Cord clamps were also available in all the facilities.

Table 1. The selected health facilities by ownership type, cadre of staff, midwife-client ratio and annual expected number of deliveries in EmNOC and BEmONC health facilities in Dedza district.

2.9.2. Process Attributes of Quality Postnatal Care

1) Supervision During the past 6 months prior to the study, 81% of the midwives had not been visited by their supervisors. Only 17% of the participants were visited once and 2% were visited twice during the last six months prior to the study. The results imply that the participants who were mostly technicians lacked supervision from the professional nurses.

2) Client Monitoring There were disparities between midwives’ responses during interview and what they did during actual practice. During the interviews, 62% of the midwives reported that they monitored mothers’ conditions at least once during the fourth stage of labor, whilst 13% stated that they monitored the mothers twice. The remaining 25% admitted that they monitored women soon after delivery due to pressure of work. However, during observation on actual practice, none of the midwives assessed women during the first hour of delivery. Furthermore, none of the women was checked when being transferred from the labor ward to the postnatal ward. The only women that were assessed soon after delivery were those who presented with a risk condition such as postpartum hemorrhage or anemia.

3) Client Examination Client examination was not done according to the RH standards. The standards stipulate that women are supposed to stay in the hospital for observation at least 72 hours after delivery. However, actual practice in the health facilities showed that in the CHAM facilities postnatal women were observed for 48 hours after delivery whilst government facilities kept them for 24 or few hours. Regarding midwives knowledge on examination times for the clients, 57% of midwives stated that examination of both women and neonates was supposed to be done only on discharge, whilst 3.3% stated that it was supposed to be done only when a client present with a complaint. Observation on practice showed that CHAM facilities were checking vital signs at least once a day because they employed support personnel for this task. However, in all government facilities, 63% of the midwives discharged mothers without checking for vital signs on the women and their neonates. A full head to toe examination as a physical assessment to ascertain fitness for a woman and her neonate before discharge was performed by only 22% of the midwives. Another 48% of midwives just examined the uterine involution and conducted perineal inspection. The rest of the midwives (30%) did not perform any postnatal examination to women and neonates on discharge.

4) Health Education and Counselling Midwives imparted partial information through group education and counselling on various child birth concepts. Maternal and neonatal danger signs were tackled by 69% of the midwives. The majority of midwives (98%) counselled women on exclusive breast feeding and its benefits whilst all of them (100%) taught women about infection prevention practices which included cord care, personal hygiene and nutrition practices. Family planning was tackled by 98% of the midwives however, midwives in CHAM facilities offered scanty information on family planning because the Roman Catholic Church which is their mother denomination does not approve the use of modern contraceptive methods by their followers. No midwife was observed teaching women on postnatal exercises (Keggel’s exercises) despite the fact that 66% of midwives mentioned during the interviews that the topic is taught to the mother during postnatal education and counselling.

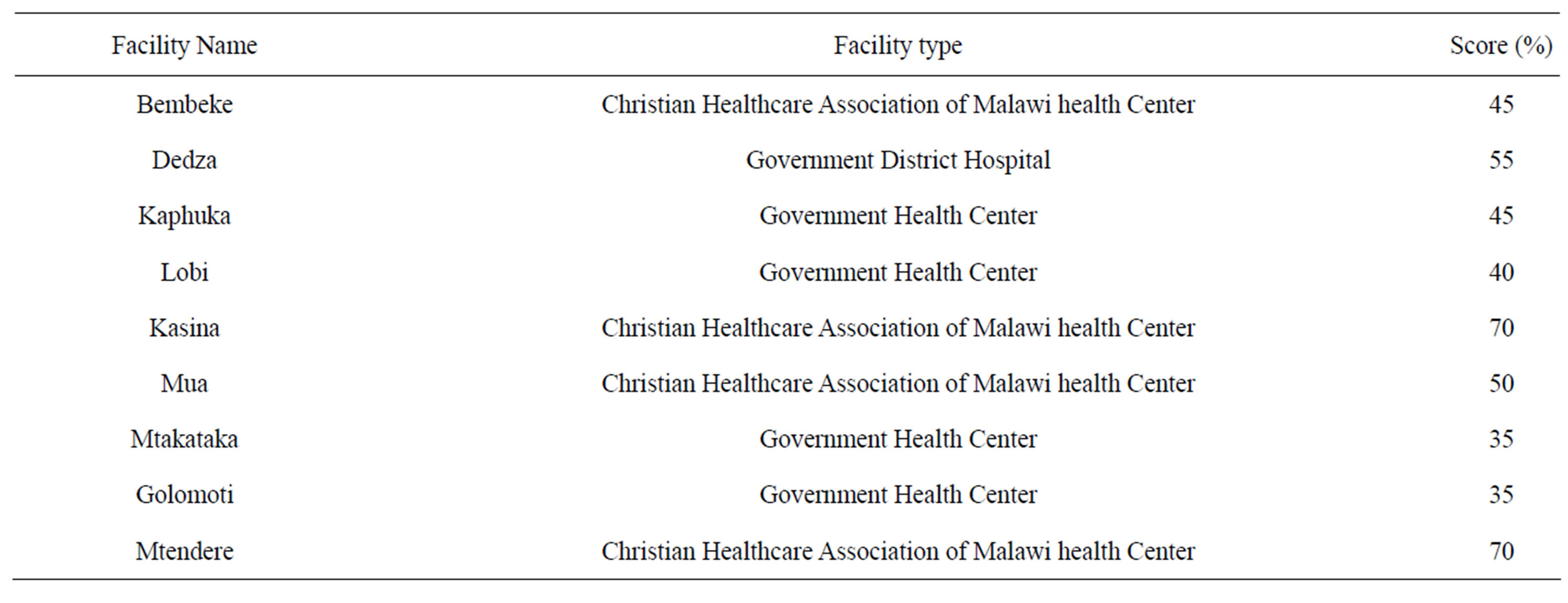

5) Outcome Attributes of Quality of Postpartum Care All the facilities scored below 80% showing that the quality of postnatal care offered to clients in the EmONC and BEmONC health facilities in Dedza was poor and below standard (Table 2). Highest scores of 70% were obtained from two facilities, Kasina and Mtendere which are both CHAM facilities. For the government facilities, Dedza district hospital obtained the highest score of 55%.

The major reasons for poor scoring on WHO guidelines and RH standards were that the midwives were not available on full time basis at the postnatal ward because they were also involved in providing other health services within the same facility. All the health facilities lacked equipment and infrastructure for providing postnatal care hence the services of the midwives did not meet the required standard of care.

3. DISCUSSION

3.1. Structural Quality Attributes

The results show that midwives in this study offered substandard postpartum care to mothers and their neonates. The midwives combined postnatal care with other services within the health facilities which made them compromise the quality of postnatal care. Due to pressure of work vital sign check on the women that delivered normally were skipped and they only performed routine check-up on women that presented with a risk factor or complaint. The Malawi Ministry of Health [12] reported that heavy workload in most government health facilities hindered the provision of quality health care according to the recommended standard of care.Similar results are reported in Australia, where a review of postnatal care revealed that the services were provided in very busy environments thus compromising the quality of care [13]. When midwives have to provide care in busy environments, the challenge they face is to prioritize some areas of health care over others. In this study, the other health services including labor and delivery were given first priority over postnatal care. Consequently, postnatal units received less attention which included human and material resource allocation.Another study by Kabene, et al., [14] reported that increased staff work overload led to low quality and productivity of health services, increased waiting times and use of personnel without required skills to perform critical interventions.

Results in this study also show that the facilities did not have appropriate infrastructure for the provision of quality postnatal care. As a result, even when midwives were available, lack of appropriate infrastructure hindered the provision of standard postpartum care to clients. Mgawadere [15] also reported that lack of proper structures for providing maternal and neonatal health services contributed to poor or partial service provision to clients and hence compromised the quality of care. Resources were inadequate for providing quality postnatal care, especially monitoring equipment, though drugs were available. These results agree with those reported by Rosy [16] in which the quality of maternal and neonatal health in most public health facilities was affected by lack of necessary equipment and resources.Similarly in Malawi, a study by Banda and Dzilankulani [17] also reported that most government health facilities in Malawi lacked necessary equipment and supplies for quality maternal care services. Resources pose a challenge to provide appropriate care to clients despite the fact that it is the basic right of every woman and neonate to have the

Table 2. Health facility scores according to the Standard of Postnatal care.

best available care that enables them go through pregnancy and childbirth in good health. There is therefore a need for adequate resources to be available in the postnatal wards because availability of supplies and essential medicines in maternal and neonatal health is an indicator of successful service implementation towards achieving MDGs 4 and 5 [18].

3.2. PNC Service Provision (Process Quality Attributes)

3.2.1. Supervision and Guidelines

Staff supervision in this study was not done frequently as stipulated in the standards. Supervision is an essential element in the improvement of provider performance because it facilitates the use of guidelines and service standards [19]. It was observed that the majority of midwives attained their qualifications over five years ago. According to JHPIEGO [20] pre-service education concentrates on acquisition of knowledge, but fails to provide the students with the skills for proficiency. Hence staff supervision by more experienced midwives could have improved the quality of care the midwives provided. Studies in Australia [21] show that supervision provides midwives with an opportunity to improve patient care in relation to maintaining standards of care. In addition, supervision provides an avenue for midwives to demonstrate active support for each other as professional colleagues, hence leads to staff motivation.

3.2.2. Guideline on Client Monitoring Immediately after Delivery

Midwives in this study did not follow stipulated guidelines in the management of postpartum women. The midwives did not monitor mothers and neonates during the first hour of delivery (4th stage of labour). Schindler [22] described this period as a distinct phase of labour with its own normal pattern and peculiar aberrations. It is a time of potential physical crisis for the mother as many questions are raised whether her uterus will normally clamp down, or blood pressure and all other systems will stabilize.Midwifery care is very vital in the postpartum because it promotes healing and the process of involution and provides emotional support. The care also prevents postpartum complications and assists in establishing successful lactation as it promotes responsible parenthood [23]. Therefore women need to be properly monitored and managed during the first 48 hours of delivery to optimize both maternal and neonatal outcomes.

3.2.3. Guideline on Client Examination in Hospital and on Discharge

Midwives in this study were aware of the need to exmine the clients on discharge however in actual practice they did not conduct the examinations. It was observed that the midwives prioritized the provision of labor and delivery services to client examination on women who were being discharged from their facilities. Similar results were reported in Cameroon and Zimbabwe where nursing care offered during labour was average but poor during postpartum [24,25]. The first 48 hours after delivery are critical because of the need to monitor vital signs which are an important indicator of adverse changes.

Staff attitude also contributed to the substandard quality of postnatal care in this study. According to the annual expected number of deliveries and the highest midwife-client ratio of 1 to 668 per annum which translates to 2 postpartum women per midwife per day, the midwives could have managed to check vital signs on all the clients. Some studies have shown that midwives were able to offer quality postnatal care even when there was staff shortage. A study conducted in Northern Botswana found that despite critical shortage of health professionals, midwives checked vital signs and fully examined women prior to discharge [26]. Hence there is a need to change the midwives’ attitudes in Dedza district so that quality postnatal care is provided.

3.2.4. Health Education and Counseling in the Postpartum

Findings show that midwives conducted health education and counseling on child birth concepts using group education approach. With this approach, the midwives did not fully cover all the topics. Consequently individual information needs were not considered and the women were denied their right to knowledge. When women know the potential causes of obstetric complications, they can take preventive measures which can in turn reduce the high rates of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. The results that individual information needs of women were not met agree with those reported by Nikiema et al., [27] and, Malata and Chirwa, [28]. In these studies results show that Malawi had the highest percentage of unmet needs for child birth information. The emphasis on ensuring that all postpartum women fully understand child birth information is one of the essential elements in maternal and neonatal health as stipulated in the Road map to acceleratethe reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality rate [29], but the reality is that the information is not being transmitted to the intended target beneficiaries.

3.3. Outcomes Quality Assessment

The results of service evaluation demonstrated that all mothers and their neonates received postnatal care services which were below standard. These results could be attributed to inadequacy of resources and the fact that midwives were also serving other wards and departments of the hospital which affected their prioritization of services. During discussions the midwives agreed that postnatal care and units were indeed neglected areas due to priorities given to other units such as the labor and delivery wards. Rawlins, et al. [30] evaluated service quality in all health facilities for performance and quality improvement in Malawi, and results show that that quality of maternal and neonatal health care was low in all facilities. The study results further showed that the availability of performance quality improvement intervention did not necessarily translate into service provision in line with the stipulated standards. The designation of EmONC and BEmONC facilities in the country was to ensure quality maternal and neonatal care, however, the situation is that the quality of care is substandard in these designated facilities. These results agree with those reported by Leight et al. [31] that almost twice the minimum number of recommended EmONC facilities existed in Malawi but only 2% of the facilities met the basic requirements for the provision of quality maternal and neonatal care.

4. CONCLUSION

The postnatal care that was provided in the EmONC and BEmONC facilities in Dedza district was substandard. Infrastructure in the health facilities was inappropriate because the facilities used improvised rooms for postnatal care. Human and material resources were inadequate for provision of comprehensive and quality postnatal care in all the facilities. The midwives combined their postnatal care with services of other departments within the facilities and the essential chemicals and supplies were in adequate. The process of service provision which entails client monitoring and examination was not in line with the Ministry of Health standards in Malawi due to lack of essential equipment. Process of client education and counseling did not meet individual client information needs because midwives used group education and skipped some topics which could have assisted some women as individuals. There is a need to strengthen the EmONC and BEmOCN facilities in Dedza so that they provide quality postnatal services to improve the maternal and neonatal outcomes. There is a need to provide basic infrastructure in all the basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care facilities. In addition, refresher training courses for midwives in maternal and neonatal health with emphasis on postnatal care are recommended. There is also a need to restructure the maternal and neonatal health departments in the facilities so that the postnatal care units become stand-alone priority sites to improve the quality of the postnatal care services rendered.

5. COMPETING INTERESTS

None of the authors has any competing interest in having this manuscript published in the Open Journal of Nursing.

6. AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

LKC conceptualized the study, collected data as part of her M.Sc. (RH) degree and drafted the manuscript. AM, AC, EC and MP were supervisors who advised LKC on the conceptualization of the study, data collection, analysis and drafting of the manuscript. All authors proof read the manuscript and approved that they be submitted to Open Journal of Nursing for publication consideration.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was conducted as part of the senior author’s Master of Science degree in Midwifery at the University of Malawi, Kamuzu College of Nursing with a scholarship from USAID. The preparation of the manuscripts for publication was funded by the University of Tromso, Norway and the Agency for Norwegian Development Cooperation

REFERENCES

- Fraser, D., Cooper, M. and Nolte, A., (2006) Myles textbook for midwives: African edition. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

- Dhaher, E., Mikolajezyk, R., Maxwell, A. and Kramer, A. (2008) Factor associated with lack of potential care among Palestine women: A cross sectional study of three clinics in the West Bank. BMC Pregnancy and Children, 8, 26.

- World Health Organization (2010) WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care: Department of making pregnancy safer. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WHO (2003) WHO technical consultation on postpartum: guidelines on postnatal care. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF Macro (2011) Malawi Demographic and Health Survey, 2010. NSO and ICF Marco, Zomba, Malawi, and Calverton, Maryland.

- Matisavich, A. and Santos, M. (2009) Inequalities in maternal postnatal visits among public and private patients. BMC Public Health, 9, 335.

- Li, X., Fortney, J., Kotelchuck, M. and Glover, L. (1999) The postpartum period; The key to maternal mortality. Science Direct Online publication, Elsevier.

- Ministry of Health (2007) Road map for accelerating the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in Malawi. Ministry of Health, Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health (2010) National EmONC assessment. Ministry of Health, Lilongwe, Malawi. http://www.afro.who.int/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=6043

- Ministry of Health (2001) Malawi national reproductive health service guidelines. http://www.k4health.org/toolkits/implants/Malawi-national-reproductive-health-service-delivery-guidelines

- Donabedian, A. (1980) Models for organizing the delivery of health services and criteria for evaluating them. Milbank Quarterly, 50,103-154. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-30

- McCarney, R., Warner, J., Iliffe, S., van Haselen, R., Griffin, M. and Fisher, P. (2007) Hawthorne effect and sampling methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7, 30.

- Rayner, A., McLachlan, H., Forster, D., Peters L. and Yelland, J. (2010) A statewide review of postnatal care in private hospitals in Victoria, Australia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 10, 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-10-26

- Kabene, S., Orchard, C., Howard, J., Soriano, M. and Leduc, R. (2006) The importance of human resources management in health care: A global context. Human Resources for Health, 4, 20. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-4-20

- Mgawadere, F. (2009) Assessing the quality of antenatal care at Lungwena Health Centre in rural Malawi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Malawi, Malawi.

- Rosy, M. (2001) Assessing quality and availability of maternal health services: Kenya. http://C:Documentsandsetting/assessingqualityandavailabilityofmaternalhealthservics

- Banda, H. and Dzilankulani, A. (2001) Malawi family planning and reproductive health project. Dedza District Assessment Report on Health Centre and Community Baseline Needs Assessment, Malawi.

- Lockwood, J., Madsen, E. and Bernstein, J. (2009) Maternal health supplies in Bangladesh. Population action International, Bangladesh.

- Kongnyuy, E., Hofman, J., Mlava, G., Mhango, C. and van den Broek, N. (2009) Availability, utilization and quality of basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care services in Malawi. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13, 687-694.

- JHPIEGO (2001) Implementing global maternal and neonatal health standards of care. JHPIEGO, Baltimore.

- Brunero, S. and Parbury, J. (2006) The effectiveness of clinical supervision in nursing: An evidenced based literature review. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 3

- Schindler, S. (1984) The fourth stage of labor: Family integration. The American Journal of Nursing, 74, 5.

- Simbar, M., Dibazari, Z., Saeidi, J. and Majd, H. (2005) Assessment of quality of care in postpartum wards of Shaheed Beheshti Medical Science University hospital. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 18, 333-342. doi:10.1108/09526860510612180

- Mbeinkong, C. (2009) Patient satisfaction with intrapartum and postpartum nursing care: The case of Buea Regional Hospital. http://www.memoireonline.com on 14/3/12

- Maimbolwa, M., Ranjo-Anderson, A.B., Ng’andu, N., Sikazwe, N. and Diwan, V. (1997) Routine care of women experiencing normal deliveries in Zambian maternity Wards. Journal of Midwifery, 13, 125-131.

- Kebalepile, T. and Sundby, J. (2006) An evaluation of the quality of care midwives provide during the postpartum period in Northern Botswana. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo.

- Nikiema, B., Beninguisse, G. and Haggerty, J.L. (2009) The extent to which women recall receiving information about pregnancy complications. Health Policy and Planning, 24, 367-376.

- Malata, A. and Chirwa, E. (2011) Assessment of the effectiveness of the childbirth education in Malawi. African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 5, 67-72.

- Ministry of Health (2006) Malawi national reproductive health service guidelines. JHPIEGO/USAID, Baltimore.

- Rawlins, B., et al. (2011) Reproductive health services in Malawi: An evaluation of a quality improvement intervention. Midwifery, 29, 53-59.

- Leight, B., Mwale, T., Lazaro, D. and Lunguzi, J. (2008) Emergency obstetric care: How do we stand in Malawi? International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 101, 107-111. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.01.012

ABBREVIATIONS

BEmONC: Basic Emergency Obstetric Care;

CHAM: Christian Healthcare Association of Malawi;

EmONC: Emergency Obstetric Care;

RH: Reproductive health;

SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Scientists;

WHO: World Health Organization

NOTES

*Corresponding author.