Open Journal of Nursing

Vol. 2 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 25517 , 5 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.24050

Impacts of social desirability response bias on sexuality care of cancer patients among Chinese nurses

![]()

1Department of Nursing Studies, Huaihua Medical College, Huaihua, China

2School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health System, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

3Department of Health and Physical Education, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong, China

Email: *Hchloezengyc@hotmail.co.uk

Received 3 August 2012; revised 12 September 2012; accepted 13 October 2012

Keywords: Social Desirability; Response Bias; Chinese Nurses; Sexuality; Cancer Patients

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to detect social desirable response bias on Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care of cancer patients. A cross-sectional self-reported questionnaire based survey was used. Measures included a 12-item Inventory of Sexuality Attitude and Belief Survey (SABS) and a 10-item Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Total social desirability scores were significantly correlated with four individual items of the SABS, and significantly predicted the total SABS scores (β = −0.155, p = 0.028). Before controlling social desirability variable, nurses’ age, marital status, years of working experience, and working units were significantly correlated with total SABS scores. After controlling social desirability variable, only nurses’ age and working units were statistically significant predictors of SABS. Social desirable response bias had impacts on Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care of cancer patients. Study findings demonstrated that social desirable response bias would potentially jeopardize human sexuality assessment and counseling in nursing practice. Controlling social desirable response should consider using a social desirability scale to detect and control potential social desirability bias during data analysis.

1. INTRODUCTION

This study aimed to examine the effect of social desirability response bias in a study of Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care of cancer patients, which might potentially jeopardize human sexuality assessment and counseling in nursing practice. Social desirability is a tendency for respondents to present a favorable image of themselves [1]. Social desirability response bias is a type of information bias and occurs when study participants respond in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others [2]. Nursing or health care related research often covers socially sensitive topics where constructs being measured are laden with social value judgments, both positive and negative. The validity of these sensitive research studies is potentially threatened by social desirability response bias [3]. A recent review found there were 14,275 questionnaire-based research studies listed on CINAHL from 2004-2005, and concluded that a proportion of conclusions reported in nursing and allied health journals obtained using questionnaires could be flawed due to the social desirable response bias [4].

One mechanism for controlling social desirable response bias is to use social desirability scales in conjunction with the data-gathering tool for the phenomenon being investigated [5], so that each participant will return scores on both scales that may then be compared. The most commonly-used scale to measure social desirability is the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale (MCSDS), a standard scale originally developed in 1960. The MCSDS scale is designed to assess social desirability bias, by asking participants to indicate true or false to 33 items. Examples of the items are as follow: “There have been times when I was quite jealous of the good fortune of others”; “I have almost never felt the urge to tell someone off”; and “I am sometimes irritated by people who ask favors of me”. Because of the length of the original scale, revised scales have whittled down the number of items to which subjects have to respond, and the version used in the current study was the 10-item scale (MCSDS-10) designed by Strahan and Gerbasi [6].

A high score on the MCSDS-10 signals a tendency to give high levels of social desirability responses. If respondents who register high on the MCSDS-10 also show higher scores on items of a questionnaire that capture a social desirability phenomenon (such as, in this case, open and positive attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care) compared to the rest of the sample, then one explanation is that they are responding in a social desirability way rather than giving an honest answer. Another explanation that must be considered is that what is considered a social desirability response in one culture may not be so in another.

To date, the only other study used the same two instruments (the SABS and the MCSDS-10) in the research being reported here was conducted in the USA by Reynolds and Magnan [7]. Indeed it was Reynolds and Magnan who developed and tested the SABS survey on nurse respondents, and found the SABS to be an internally consistent measure of obstacles to engaging in assessment/counseling around human sexuality in nursing practice. Respondents also completed the MCSDS-10 short form; results indicated that respondents’ SABS scores did not correlate significantly with scores achieved on the MCSDS-10. Reynolds and Magnan concluded that respondents appeared to be answering the SABS items honestly rather than presenting a social desirability version of themselves [7]. Furthermore, the nurses’ age and years of experience as a nurse did not correlate with scores on the SABS. Reynolds and Magnan further suggest that the SABS needed to be replicated on a larger and more diverse group of nurses beyond the site in which it was initially developed. Thus, using exactly the same instrument, the study was replicated on a sample of Chinese nurses.

The objective of this study was to detect social desirable response bias on Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care of cancer patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Participants

Study participants were 199 Chinese hospital nurses from a Tumor hospital. All were female and their ages ranged from 19 - 50 years old. Their highest education levels ranged from diploma to master degree. Nearly half of them were married. Their working experience ranged from 1 - 25 years, their working positions include nurse, experienced nurse, associate head nurse and head nurse. These nurses were recruited from 4 working units (gynecologic cancer, breast cancer, medical and surgical oncology units, respectively).

2.2. Procedures

Ethical approval was obtained from the Tumor Hospital’s Human Subjects Research Review Committee. Participants were assured confidentiality during the informed consent process and were free to withdraw from the study. Nurses were assured that the survey was anonymous and their names were not required to fill in the questionnaires.

2.3. Measures

Survey included a short demographic sheet to measure Chinese nurses’ age, education level, marital status, working experience, working position and units. A 12-item Inventory of Sexuality Attitude and Belief Survey (SABS) developed by Reynolds and Magnan [7] was used to measure Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuallity of cancer patients. The scale of SABS was found to have good reliability and validity, reported in previous studies [8,9].

The short form of Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS-10) was used to detect the effect of social desirability on nurses’ SABS scores. The shortform of MCSDS was found to have good reliability and validity in previous studies [10,11]. The translation of MCSDS-10 into Chinese was done by a nurse researcher, who is a native Chinese speaker and with native Englishspeaking countries’ nursing education background. Three bilingual (Chinese and English) nursing academics then validated this Chinese version of MCSDS-10. The face validity of the Chinese version MCSDS-10 was assessed by 8 nursing research students and 10 Chinese hospital nurses. The internal consistency of the MCSDS-10 was established by Cronbach alpha of 0.819 (n = 199).

2.4. Data Collection and Data Analysis

Data were collected by a nurse with research training and were collected on December 2009. All the data were entered and analyzed using PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics was used to describe the mean score of social desirability and the SABS, correlation analysis was used to identify the relationships among individual items of SABS with social desirability and stepwise hierarchical regression analysis was used to identify the predictors of SABS from nurses’ demographic factors while statistically controlling for social desirability.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effects of Social Desirability on the Individual Items of SABS

The mean of social desirability score among these 199 Chinese nurses was 7.02 (Standard Deviation = 1.74; range = 0 - 10). From existing literatures there is no cut off point score for the short-version of MCSDS-10. According to Andrew and Meyer [12], the 33 item of MCSDS when participants were non-socially desirable responding was 15. The possible cut off point of MCSDS-10 may be 5. In this study, only a small portion of Chinese nurses’ social desirability mean scores were less than 5. Another principle to judge whether participants giving social desirability responses or non-social desirability responses, Edens et al. [13] suggest that designating a high scorer on the standard MCSDS as someone who scored more above the mean for the sample could be taken as social desirability response. Nearly fifty percent (45.2%, n = 90) of Chinese nurses’ social desirability mean scores were higher than 7. Therefore, a large proportion of Chinese nurses in this study were likely to give social desirability responses.

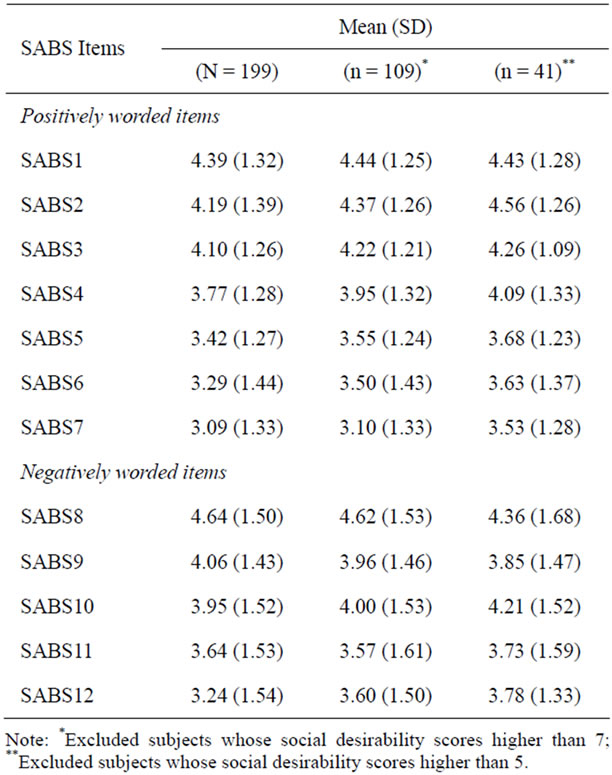

The Inventory of SABS includes 12 items: 7 items were positively worded, and 5 items were negatively worded. Positively worded items were reversely scored for the calculation of means. Higher mean score indicates higher levels of barriers for nurses to address patients’ sexuality concerns. If nurses gave social desirability responses for the SABS items, it would result in lower mean score for individual items. Table 1 lists Chinese nurses’ mean SABS scores. After excluding higher social desirability scores, there was an increasing of almost all SABS items’ mean scores.

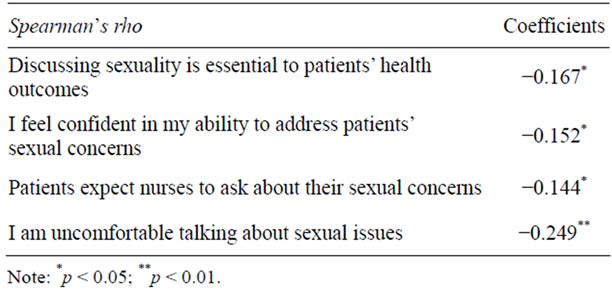

Spearman’s correlation between the total social desirability score and the individual items of SABS scores ranged from rs = −0.144 (“Patients expect nurses to ask about their sexual concerns”) to rs = −0.249 (“I am uncomfortable talking about sexual issues”) (Table 2).

3.2. Effects of Total Social Desirability Score on Cofounding the Socio-Demographic Predictors of SABS

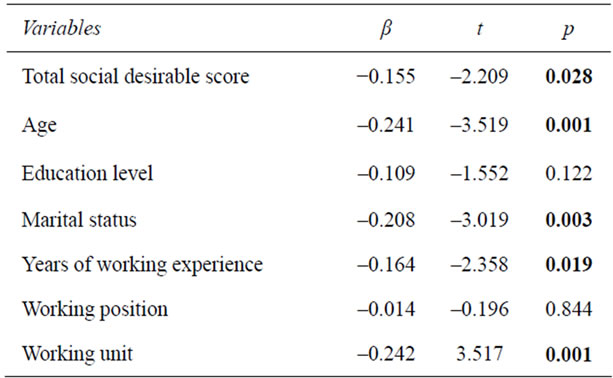

Total social desirability scores were significantly correlated with four individual items of the SABS, and significantly predicted the total SABS scores (β = −0.155, p = 0.028). Before controlling social desirability variable, nurses’ age, marital status, years of working experience and working units were significantly correlated with total SABS scores (Table 3).

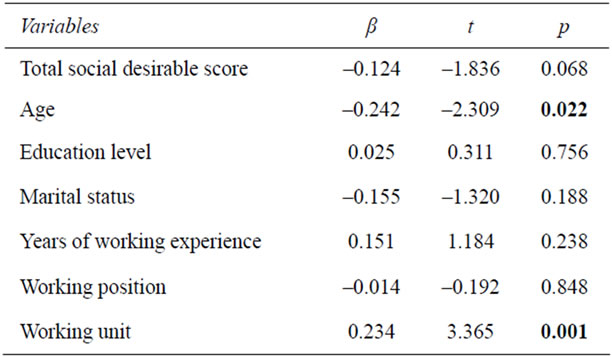

After controlling for social desirability variable, nurses’ age and working units were statistically significant predictors of SABS. The combination of these two factors explained 11.2% of the variance in attitudes and belief toward sexuality care (F = 4.569, df = 7.119, p < 0.001) (Table 4).

4. DISCUSSION

After excluding subjects whose total social desirability scores higher than 7 (the mean score of Chinese nurses) or 5 (the possible cut off point score of the MCSDS-10 estimated from the original version of MCSDS-33), the mean score of SABS items was increased. It indicated that Chinese nurses with higher social desirability scores would have the tendency of reporting lower level barriers

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of SABS items.

Table 2. Correlation analysis of SABS items with social desirability scores.

Table 3. Regression analysis of predictors of nurses’ demographic variables without controlling for social desirability score.

Table 4. Regression analysis of predictors of nurses’ demographic variables after controlling for social desirability score.

in addressing patients’ sexuality concerns than their honest responses would report. Yet, there was a decreasing of two items’ [“Most hospitalized patients are too sick to be interested in sexuality”; “Sexuality is too private issue to discuss with patients”] mean scores. This may be confounding another type of response bias such as acquiescent response bias, which might be “considered as agreeing with items independently of content, whereas social desirability is dependent on the content” [5]. Acquiescent responses happen more often among individuals from collective culture background [14]. The orientation of Chinese culture is more than collectivistic. Thus, conducting sensitive research topics among Chinese population or people from collectivistic cultural background need consider both social desirability and acquiescent response biases.

Although one similar study conducted among nurses in the USA reported that social desirability response bias did not have a significant influence on nurses’ SABS scores [7]. In this study, Chinese nurses’ social desirability scores did correlate significantly with scores obtained by the MCSDS-10. Social desirability scores were also significantly correlating four individual items of SABS, even though these correlations were in the small effect size (rs = 0.144 - 0.249). According to Cohen’s [15] descriptive scheme, correlations in the small effect size range was rs from 0.1 to 0.3. Hence, findings of this study still indicate that Chinese nurses had the tendency of giving social desirability response to the SABS items rather than giving honest responses, especially among these four SABS items listed in Table 2. Future research should revise these four items in a way that reduces the tendency of social desirability response.

Multiple linear regressions weighted between nurses’ socio-demographic predictors and SABS outcome variables. The results of this study clearly demonstrated the presence of social desirability effect confounding the pre-dicting factors of SABS. Before and after controlling social desirability effects, the predicting factors of SABS were different. Hence, it is recommended that social desirability effect need to be appropriately assessed during data analysis.

Even though the validity of self-reported sensitive research topics is threatened by social desirability response bias, questionnaire-based research was widely used in research on these topics [3]. The findings of this study demonstrated that social desirability response bias would potentially jeopardize human sexuality assessment and counseling in nursing practice. Potential strategies to reduce social desirability response bias could be implemented in the whole research process. From the beginning of item and instrument development, Rockwood and Constantine [16] recommended that during the development of desirable or sensitive issues, it should depersonalize the question as much as possible. In the stage of data collection, it should use a social desirability scale, and ensuring participants’ anonymity can reduce social desirability bias in studies [16]. Based on findings in this study, it could use hierarchical regression analysis to control social desirability effect on the predictors of SABS.

Although this study adopted a cohort of sample of Chinese nurses from a tumor hospital, the cross-sectional nature of this study resulted in limited findings. Also, this study used a short version of MCSDS-10 may not have given a comprehensive image/reflection of what is considered to be social desirability in this study population.

5. CONCLUSION

Social desirability response bias had impacts on the nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care in cancer patients. This study points to that research using self-reported questionnaire based studies, especially in sensitive research topics such as sexuality outcome studies, should consider using a social desirability scale to detect and control potential social desirability response bias during data analysis.

REFERENCES

- Petroczi, A. and Nepusz, T. (2011) Methodological considerations regarding response bias effect in substance use research: Is correlation between the measured variables sufficient? Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6, 1. Hhttp://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/6/1/1

- Stuart, G.S. and Grimes, D.A. (2009) Social desirability bias in family planning studies: A neglected problem. Contraception, 80, 108-112. Hdoi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.009

- Moshagen, M., Musch, J., Ostapczuk, M. and Zhao, Z. (2010) Reducing socially desirable responses in epidemiologic surveys: An extension of the randomized-response technique. Epidemiology, 21, 379-382. Hdoi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61dbc

- van de Mortel, T.F. (2008) Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 40-48.

- Verardi, S., Dahourou, D., Ah-Kion, J., Bhowon, U., Tseung, C.N., Amoussou-Yeye, D., Adjahouisso, M., Bouatta, C., Dougoumalé Cissé, D., Mbodji, M., Barry, O., Minga Minga, D., Ondongo, F., Tsokini, D., Rigozzi, C., Meyer de Stadelhofen, F. and Rossier, J. (2010) Psychometric properties of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale in eight African countries and Switzerland. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41, 19-34. Hdoi:10.1177/0022022109348918

- Strahan, R. and Gerbasi, K.C. (1972) Short, homogenous versions of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28, 191-193. Hdoi:10.1002/1097-4679(197204)28:2<191::AID-JCLP2270280220>3.0.CO;2-G

- Reynolds, K. and Magnan, M.A. (2005) Nursing attitudes and beliefs toward human sexuality: Collaborative research promoting evidence-based practice. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 19, 255-259. Hdoi:10.1097/00002800-200509000-00009

- Magnan, M.A. and Reynolds, K. (2006) Barriers to addressing patient sexuality concerns across five areas of specialization. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 20, 285-292. Hdoi:10.1097/00002800-200611000-00009

- Zeng, Y.C., Li, Q.P., Wang, N., Ching, S.S.Y. and Loke, A.Y. (2011) Chinese nurses’ attitudes and beliefs toward sexuality care in cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 34, E14-E20. Hdoi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f04b02

- Reynolds, W.M. (1982) Development of reliable and valid short form of the Marlowe-Crown scale of social desirability. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 119-125. Hdoi:10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<119::AID-JCLP2270380118>3.0.CO;2-I

- Rudmin, F.W. (1999) Norwegian short-form of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Scandiavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 229-233. Hdoi:10.1111/1467-9450.00121

- Andrews, P. and Meyer, R. (2003) Marlow-Crowne social desirability scale and short form C: Forensic norms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 483-492. Hdoi:10.1002/jclp.10136

- Edens, J., Buffington, J., Tominic, T. and Riley, B. (2001) Effects of positive impression management on the psychopathic personality inventory. Law and Human Behavior, 25, 235-256. Hdoi:10.1023/A:1010793810896

- Smith, P.B. (2004) Acquiescent response bias as an aspect of cultural communication styles. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 50-61. Hdoi:10.1177/0022022103260380

- Cohen, J. (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale.

- Rockwood, T. and Constantine, M. (2009) Item and instrument development to assess sexual function and satisfaction in outcomes research. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, 20, S57-S64. Hdoi:10.1007/s00192-009-0842-9

NOTES

*Corresponding author.